Study raises questions about autism-gut connection

Children with autism are no more likely than healthy children to have some of the gastrointestinal symptoms — such as diarrhea, acid reflux and abdominal discomfort — previously tied to the disorder, according to one of the first long-term investigations of the supposed link.

Children with autism are no more likely than healthy children to have some of the gastrointestinal symptoms — such as diarrhea, acid reflux and abdominal discomfort — previously tied to the disorder, according to one of the first long-term investigations of the supposed link.

Other digestive problems, however, such as constipation and picky eating, occur twice as often in children with autism, the study found. The results were published online 27 July in Pediatrics1.

Studies since the 1960s have calculated wildly different rates of various gastrointestinal (GI) woes in children with autism — ranging in prevalence from 9 to 84 percent2. Scientists have not reached a consensus on the true rate, primarily because few relevant epidemiological studies have been done on this population.

In the new study, drawing from a county database of medical history records, researchers tallied the number and type of GI problems that occurred in the early lives of 121 Minnesotans with autism and 242 healthy controls. By 20 years of age, 77 percent of the participants with autism and 72 percent of controls reported at least one of five common GI symptoms. The difference did not meet statistical significance.

“Certainly there have been many threads of investigation in the literature that have raised the possibility that there is some gut issue that’s involved, either along with, or as a potentially contributing factor to, autism,” says lead investigator William Barbaresi, director of the Developmental Medicine Center at Children’s Hospital Boston. Barbaresi conducted the work while an associate professor of pediatrics at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“Our answer to the question is that children with autism are no more likely than children without autism to have GI problems in an overall sense,” he adds.

When each symptom was compared individually, however, the researchers did find significant differences in rates of constipation and food selectivity.

Barbaresi hypothesizes that these are secondary symptoms that stem from more fundamental autism behaviors. For instance, a need for sameness, when applied to diet, could lead to inadequate consumption of fiber and fluids, which could in turn lead to constipation.

Others say that the new findings do not rule out a more meaningful association between autism and the gut.

“It’s a very well-done article in which [the authors] were really attempting to put the question to rest,” says Mark Gilger, section head of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition at Baylor College of Medicine, who was not involved with the work. “But, in my opinion, it is not put to rest.” That’s partly because the study was retrospective, meaning it relied on historical records of symptoms, which may be incomplete or inaccurate.

Subgroup speculation:

The new study found that children with autism are 1.3 times more likely to have diarrhea and 1.5 times more likely to have acid reflux compared with controls.

Because of the relatively small sample, however, it’s difficult to know whether the differences are related to autism or to chance, notes Daniel Campbell, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Southern California. “In a larger sample, those trends may prove significant.”

What’s more, the study makes no note of the duration or severity of clinical symptoms. In follow-up work, “it will also be important to distinguish between chronic GI conditions that last months or years, and GI disturbances that last only a few days,” Campbell says.

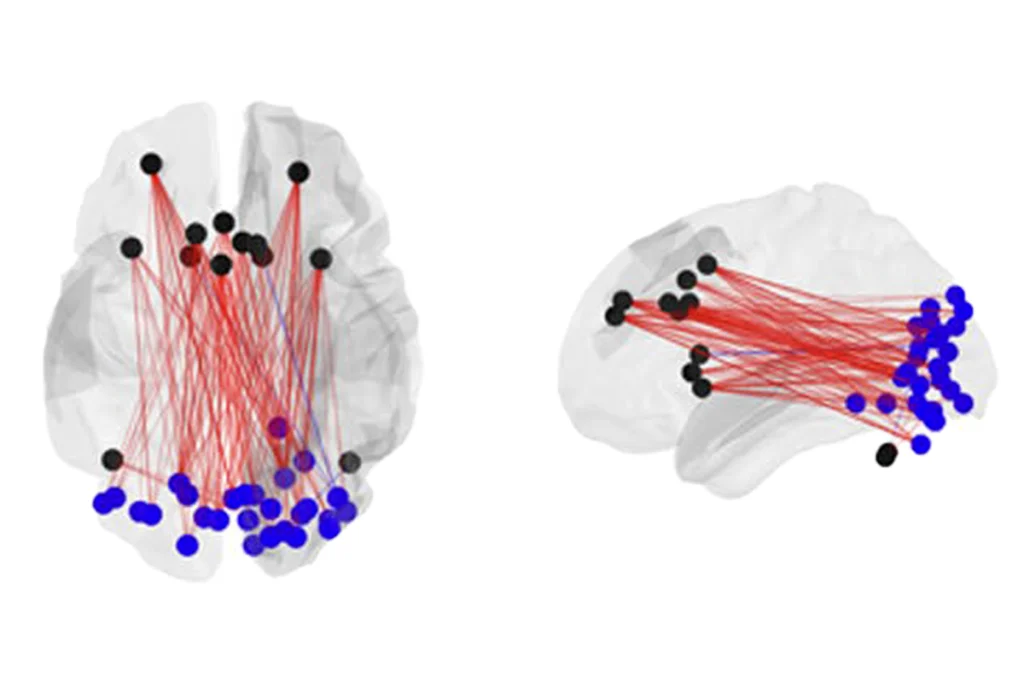

Campbell and other researchers also point to recent genetic studies that bolster the idea that — at least in some subgroups — some of the same biological mechanisms underlie autism and gut ailments.

Earlier this year, Campbell and his colleagues showed that a gene called MET, which is involved in both brain development and repair of cells that line the intestine, is associated with autism and chronic constipation, diarrhea and irritable bowel syndrome3.

There may be subgroups of people with autism who should be examined more closely in genetic studies, Gilger says. For example, girls and women with Rett syndrome — a rare genetic disorder known to cause features of autism — have been shown to have swallowing problems and acid reflux4. More studies will be needed to uncover the relationship between genes and these problems, he adds.

Besides genes, there could also be environmental explanations for gastrointestinal trouble in people with autism, says Derrick MacFabe, director of the Kilee Patchell-Evans Autism Research Group at the University of Western Ontario. For instance, his group has found evidence that, when injected into the cerebrospinal fluid of a rat brain, a fatty acid produced by many gut bacteria causes brain inflammation and autism-like behaviors such as hyperactivity, repetitive movements and social impairment5.

“Propionic acid or related gut metabolites may provide a possible testable link between the behavioral and gastrointestinal symptoms of autism,” he says.

The fatty acids, which are present in refined wheat and dairy products, are known to alter gut activity, providing a potential mechanism for symptoms such as constipation and diarrhea seen in autism.

Such symptoms may result from a wide array of medical conditions, however. That’s why in future studies, researchers should follow children over time, and consult a gastroenterologist for more specific diagnoses, MacFabe says.

References:

-

Ibrahim S. et al. Pediatrics 124, 680-686 (2009) Abstract

-

Gilger M. and Redel C.A. Pediatrics 124, 796-798 (2009) Abstract

-

Campbell D.B. et al. Pediatrics 123, 1018-1024 (2009) PubMed

-

Motil K.J. et al. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 29, 31-37 (1999) PubMed

-

MacFabe D.F. et al. Behav. Brain Res. 176, 149-169 (2007) PubMed

Recommended reading

How pragmatism and passion drive Fred Volkmar—even after retirement

Altered translation in SYNGAP1-deficient mice; and more

CDC autism prevalence numbers warrant attention—but not in the way RFK Jr. proposes

Explore more from The Transmitter