The Nine Points (Mildred Creak and Working Party, 1961)

In 1961, British psychiatrist Mildred Creak published the first list of behavioral observations to identify children with autism.

These points gave a new direction to research into causes of autism, as they highlighted the behaviors that are critical to the disorder and needed to be explained.

— Uta Frith

1. Gross and sustained impairment of emotional relationships with people. This includes the more usual aloofness and the empty clinging (so-called symbiosis): also abnormal behaviour towards other people as persons, such as using them, or parts of them, impersonally. Difficulty in mixing and playing with other children is often outstanding and long-lasting.

2. Apparent unawareness of his own personal identity to a degree inappropriate to his age. This may be seen in abnormal behaviour towards himself, such as posturing or exploration and scrutiny of parts of his body. Repeated self-directed aggression, sometimes resulting in actual damage, may be another aspect of his lack of integration (see also point 5), as also the confusion of personal pronouns (see point 7).

3. Pathological preoccupation with particular objects or certain characteristics of them, without regard to their accepted functions.

4. Sustained resistance to change in the environment and a striving to maintain or restore sameness. In some instances behaviour appears to aim at producing a state of perceptual monotony.

Related article:

5. Abnormal perceptual experience (in the absence of discernible organic abnormality) is implied by excessive, diminished, or unpredictable response to sensory stimuli for example, visual and auditory avoidance (see also points 2 and 4), insensitivity to pain and temperature.

6. Acute, excessive, and seemingly illogical anxiety is a frequent phenomenon. This tends to be precipitated by change, whether in material environment or in routine, as well as by temporary interruption of a symbiotic attachment to persons or things (compare points 3 and 4, and also 1 and 2).

(Apparently commonplace phenomena or objects seem to become invested with terrifying qualities. On the other hand, an appropriate sense of fear in the face of real danger may be lacking.)

7. Speech may have been lost or never acquired, or may have failed to develop beyond a level appropriate to an earlier stage. There may be confusion of personal pronouns (see point 2), echolalia, or other mannerisms of use and diction. Though words or phrases may be uttered, they may convey no sense of ordinary communication.

8. Distortion in motility patterns-for example, (a) excess as in hyperkinesis, (b) immobility as in katatonia, (c) bizarre postures, or ritualistic mannerisms, such as rocking and spinning (themselves or objects).

9. A background of serious retardation in which islets of normal, near normal, or exceptional intellectual function or skill may appear.

Recommended reading

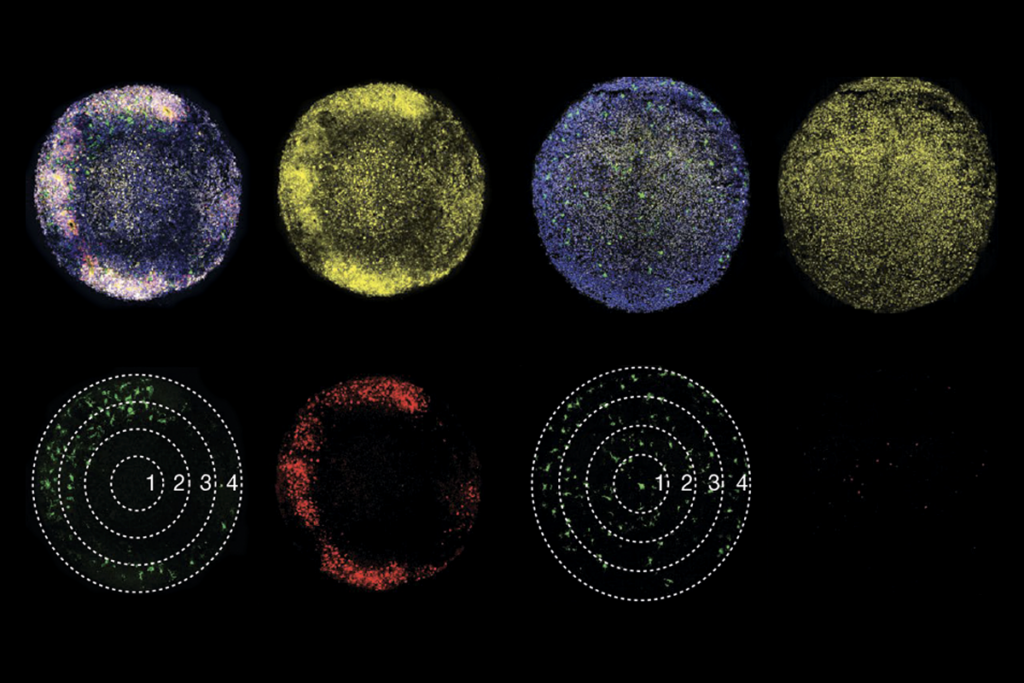

Altered excitatory circuits in CHD8-deficient mice; and more

Why hype for autism stem cell therapies continues despite dead ends

Explore more from The Transmitter

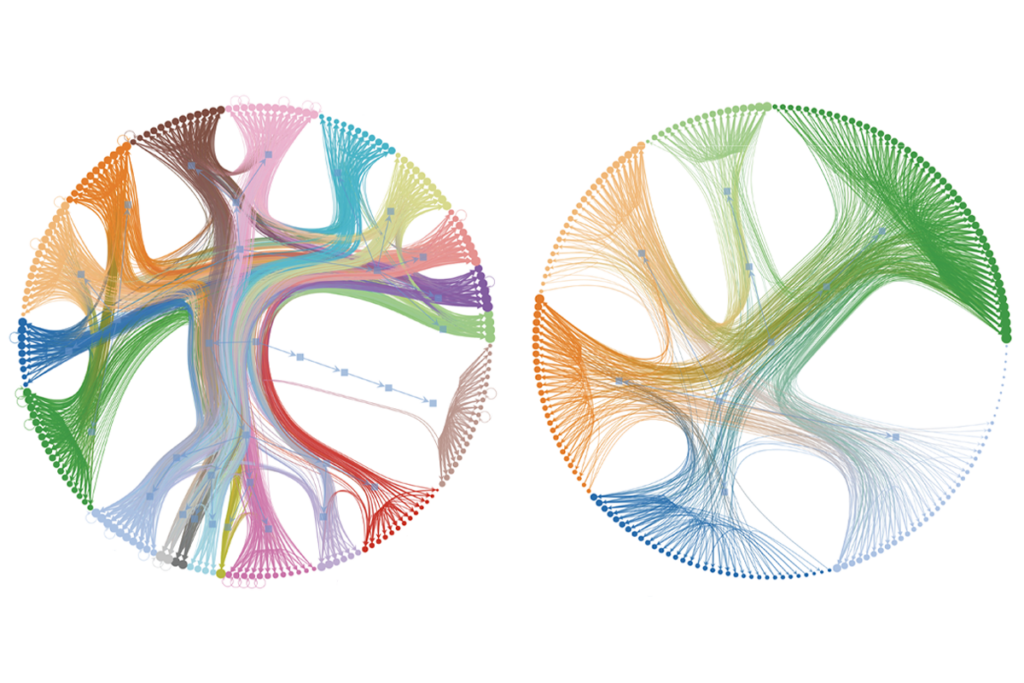

Worms help untangle brain structure/function mystery

Xaq Pitkow shares his principles for studying cognition in our imperfect brains and bodies