This paper changed my life: Ishmail Abdus-Saboor on balancing the study of pain and pleasure

A 2013 Nature paper from David Anderson’s lab revealed a group of sensory neurons involved in pleasurable touch and led Abdus-Saboor down a new research path.

Answers have been edited for length and clarity.

What paper changed your life?

Genetic identification of C fibres that detect massage-like stroking of hairy skin in vivo. Vrontou S., Wong A.M., Rau K.K., Koerber H.R., Anderson D.J. Nature (2013)

This is a paper of both technical and conceptual breakthroughs.

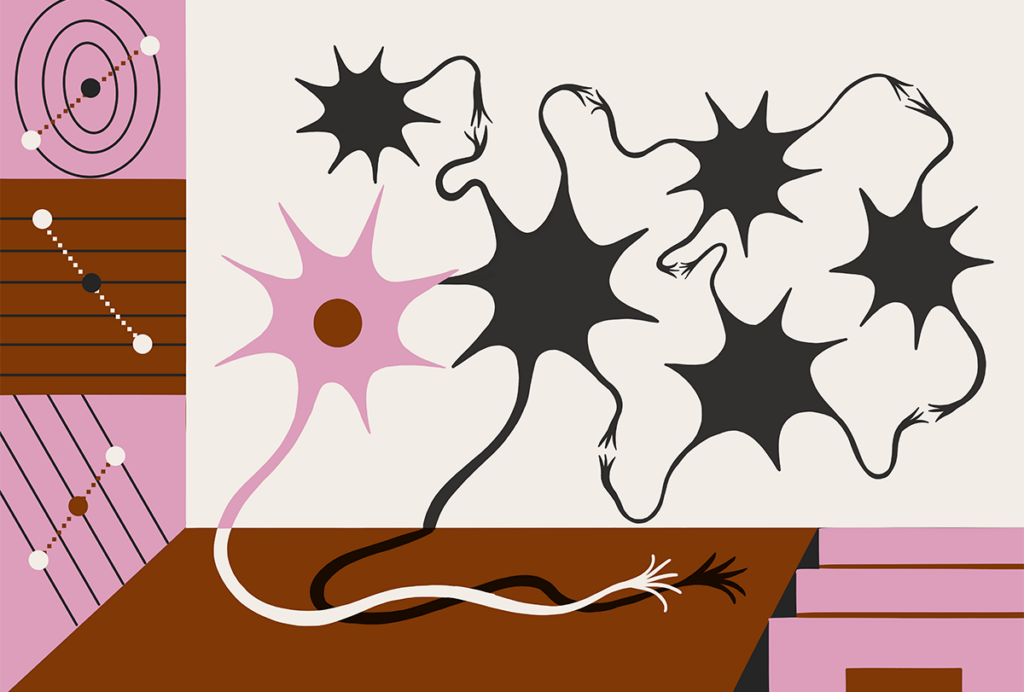

In this paper, David Anderson’s group developed a novel method of calcium imaging in the dorsal root ganglion in mice. They used this technique to look at the activity of sensory neurons expressing the G-protein-coupled receptor MRGPRB4 in response to different types of stimuli in the skin. They found that these sensory neurons responded only to stroking, pleasurable touch of the skin, and not to pinching or aversive stimulation.

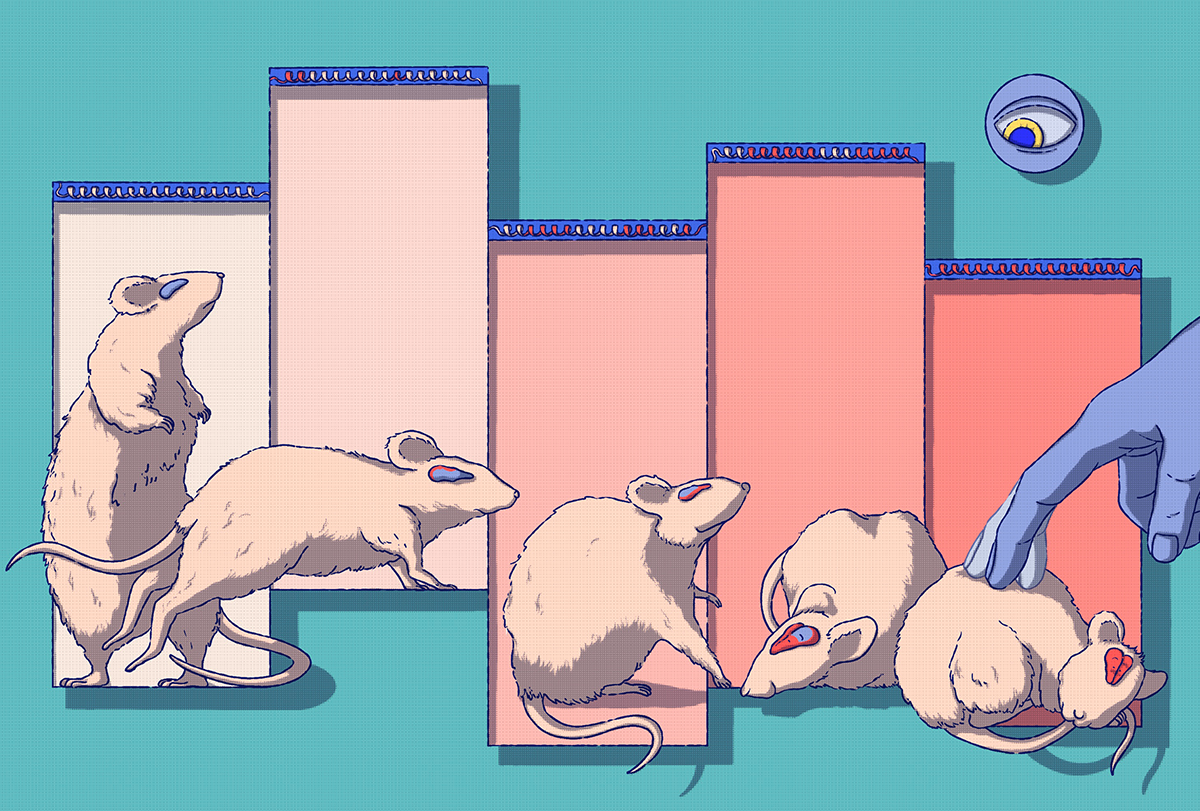

Then they asked: How do animals perceive this stimulation? What is the net output from activating these neurons? To address these questions, they developed a place preference assay, in which they chemogenetically activated MRGPRB4-positive neurons throughout the skin only when the mice entered a specific chamber in their cages. They found that the animals preferred to spend time in environments where these neurons were stimulated—kind of allowing the animals to vote with their feet.

Getting mice or any animal to show us that something is aversive is a little easier to do than to show if something is appetitive. Sometimes, the animal will just have a neutral sort of response to something pleasurable. So these are hard experiments to do. In neuroscience, we tend to deprive mice of food or water to motivate them to do something. There aren’t many studies that have shown that there are neurons that control pleasurable touch and that stimulating them is sufficient for the mice to prefer an area of the cage during the experiment. That is why this study had a major impact on the field and on me.

When did you first encounter this paper?

I was a postdoctoral researcher at the time, working with professor Wenqin Luo in the Department of Neuroscience at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. I was studying the neurological basis of pain in the peripheral nervous system, looking at a population of sensory neurons that are sisters to MRGPRB4 neurons, called MRGPRD neurons. As I read this paper back then, it made me consider how molecular activation of sensory neuron types relates to behavior.

I was also thinking if I had a lab one day, who might want to join? I thought, if I only studied pain, maybe this would limit the type of people I could recruit. Why not study pleasure also? There might be some people who are put off from studying pain in mice but would be a little more excited to do that if they had the option to study pleasure as well. So that was one idea I had immediately after reading this paper—studying pleasurable touch could be a way to diversify my portfolio.

Why is this paper meaningful to you?

This paper spurred a conversation with David Anderson at a conference years ago. It was a neuroscience conference, and I was the only person there with a poster on the peripheral nervous system. I didn’t get much traction at my poster and was kind of an outsider at this meeting. I saw David Anderson in the hallway. I didn’t know him and had no connection to him, but I had read this paper on MRGPRB4 neurons, so I worked up the courage to introduce myself. I told him that I was working on the MRGPRD pain neurons and that I would love for him to come by my poster to get his feedback on my data. He said, “Thanks for introducing yourself. Stand by your poster. In about 20 minutes, I’ll be there.”

So I waited, and he came by. This did wonders for my confidence. It took a lot for me to step outside my comfort zone and talk to such an eminent scientist as a lowly postdoc. We had a good conversation, and he thought the work I was doing was really exciting. Someone of David’s caliber acknowledging and validating your work can motivate you to keep going. That conversation did that for me. Now I’m on the other side at meetings, and people ask me to come to their poster. I remember that encounter, and I think, “Let me give somebody five minutes of my time.”

How did this research change how you think about neuroscience and influence your scientific trajectory?

At the time, I didn’t have as much interest in studying touch, but reading this paper had me thinking about ideas. When I started my own lab in 2018, alongside our work in pain, we started a project on social touch following up on this study.

In this study, the researchers looked at one type of behavior with the place preference assay. But there’s a whole host of ethologically relevant behaviors associated with pleasurable touch, including mating and mother-pup interactions. So I spent some time studying these behaviors and developing tools to measure pleasurable touch. I thought this could be a unique entry point for my lab to examine which naturally occurring behaviors require these neurons. There were also no connections made to the spinal cord or brain in this study, so I wanted to follow up and look into this body-to-brain circuit.

Studying pleasurable touch is challenging. When you activate pain neurons through the skin, you get prototypic aversive responses that are intuitive, like when you withdraw your hand from a hot stove. I think one reason why the touch behavioral assays have kind of lagged behind the pain assays is that the readouts are not as clear and intuitive.

Touch is something people think about a lot. They can easily relate to it. But when you stop and ask, “Well, how does that work?” it’s kind of unclear. I like to work on problems where there’s still room to make a big impact. So this paper and area of research checked a lot of boxes for me.

Is there an underappreciated aspect of this paper you think other neuroscientists should know about?

Something that might be buried in the details is the innovative calcium imaging preparation they developed. The way that most people do calcium imaging in this field is to measure calcium at the soma. Anderson’s group instead recorded in the terminals in the spinal cord of these dorsal root ganglion neurons. Recording at the terminals is challenging and not easy to replicate. There’s calcium at the cell body, but it’s not as intense or robust as in the presynaptic terminal, where they did their recordings. I think this allowed them to detect these subtle changes that would have been harder to appreciate with some other versions of calcium imaging.

Recommended reading

This paper changed my life: John Tuthill reflects on the subjectivity of selfhood

The best of ‘this paper changed my life’ in 2025

Explore more from The Transmitter