This paper changed my life: Nancy Padilla-Coreano on learning the value of population coding

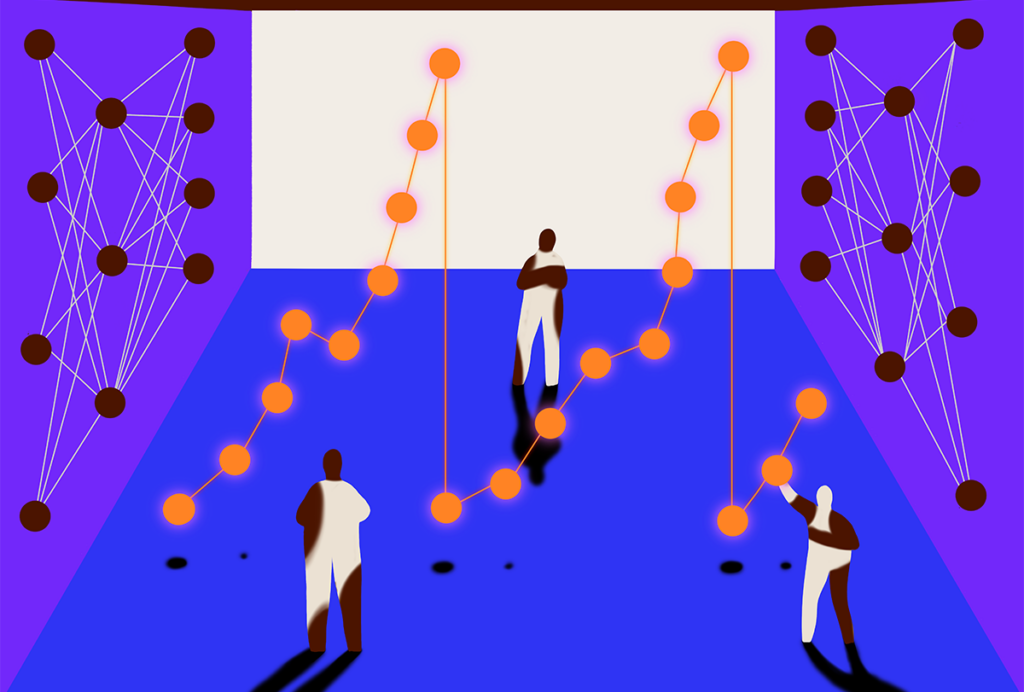

The 2013 Nature paper by Mattia Rigotti and his colleagues revealed how mixed selectivity neurons—cells that are not selectively tuned to a stimulus—play a key role in cognition.

Answers have been edited for length and clarity.

What paper changed your life?

The importance of mixed selectivity in complex cognitive tasks. Rigotti M., Barak O., Warden M.R., Wang X.J., Daw N.D., Miller E.K., Fusi S. Nature (2013)

In this study, the researchers investigated how neurons in the prefrontal cortex encode behaviorally relevant activity for a cognitive task in nonhuman primates. They analyzed neural activity in monkeys during an object sequence memory task to determine if mixed selectivity neurons—cells that do not selectively respond to a stimulus—are required for task-relevant behaviors. They also developed a new computational method to analyze mixed selectivity neurons.

Typically, people in this field only paid attention to whichever neurons selectively responded to a given stimulus. That was how I learned about stimulus response early in my career. People would say, “How many neurons responded to your cue? OK, those are the important neurons.” And then we ignored everything else. In this paper, they found that mixed selectivity neurons carry way more computational power than previously thought and encode important information about behavioral cues. It was mind-blowing.

When did you first encounter this paper?

I was a second-year graduate student at Columbia University. Everybody was talking about this paper because some of the authors were at Columbia. Anytime someone in your department gets a Nature paper, everyone is excited to talk about it.

At the time, I was learning to do in-vivo electrophysiology, recording in the medial prefrontal cortex like they did in this paper but during a different, much simpler behavioral task in mice. I was trying to get comfortable with systems neuroscience because my background was in behavioral neuroscience and pharmacology—this paper was a big part of that journey.

Why is this paper meaningful to you?

It’s a paper that I’ve thought about throughout my career. It took me some time to understand this paper. It took years of reading it again and again, at different periods in my career.

One thing that I kept thinking about was the question of how the prefrontal cortex can have fixed neural circuits and still have mixed selectivity neurons. When I was a postdoc, I wrote about this in a book chapter with my colleagues Austin Coley, Reesha Patel and Kay Tye. In that chapter, we built off this paper and came up with different circuit motifs that could possibly explain this. We published this in 2021, so we were still thinking about Riggoti’s findings many years later.

I also teach this paper in my graduate courses when I teach students about the prefrontal cortex and circuit motifs.

How did this challenge your previous assumptions?

I came to grad school with the assumption that single neurons encode information. I wanted to do single-cell physiology because I thought the most important unit of computation was a single neuron. In my undergrad lab, I learned that behavioral fear conditioning experiments could potentiate activity in individual neurons, so I saw the power of the analysis at the single-cell level. Reading this paper shifted my focus to neuronal population-level analysis.

The other thing that this paper made me reconsider was the concept of averaging neuronal responses during experiments. Let’s say that you’re recording in a brain area, and 20 neurons responded to your behavioral cue. What researchers would do at the time was group average responses across 20 neurons as if they were separate participants or animals in a trial. It had never occurred to me until this paper that averaging across neurons could actually get rid of information.

How did this research influence your career path?

It changed the rest of my career because now I will die on the hill that population coding is the relevant level of encoding information in the brain. And there’s now lots of evidence for this. There are many ensemble papers that show this using completely different techniques.

In my work, I don’t care about the identity of a specific neuron. I’m more interested in what a neuronal population is showing us. I no longer think that the adequate thing to do is to average across your neurons, unless you have a very specific reason to do that.

Is there an underappreciated aspect of this paper you think other neuroscientists should know about?

Maybe not underappreciated, but there are two things from this paper that took me a while to understand. One of them was learning that the brain can encode information in a nonlinear manner.

The second thing was the use of a supervised classifier or machine-learning approach, the computational methods the researchers developed to show how mixed selectivity neurons encode information. A supervised classifier is a statistical model that researchers train to learn the relationship between a label and the neural activity. In this paper’s case, the label was the monkey’s performance data during recall and recognition.

Once you’ve trained your model, you can provide data that the model has not seen before to make predictions about neuronal activity.

With this approach, the researchers had the power to remove the activity of the population of neurons that selectively responded to the stimulus, and they found that mixed selectivity neuron activity alone was sufficient to decode their label of interest.

It took me a while to get it, but once I got it, I said, “Wow, that’s so powerful.” I’ve kept this as part of my tool kit ever since.

Explore more from The Transmitter