Cell atlas cracks open ‘black box’ of mammalian spinal cord development

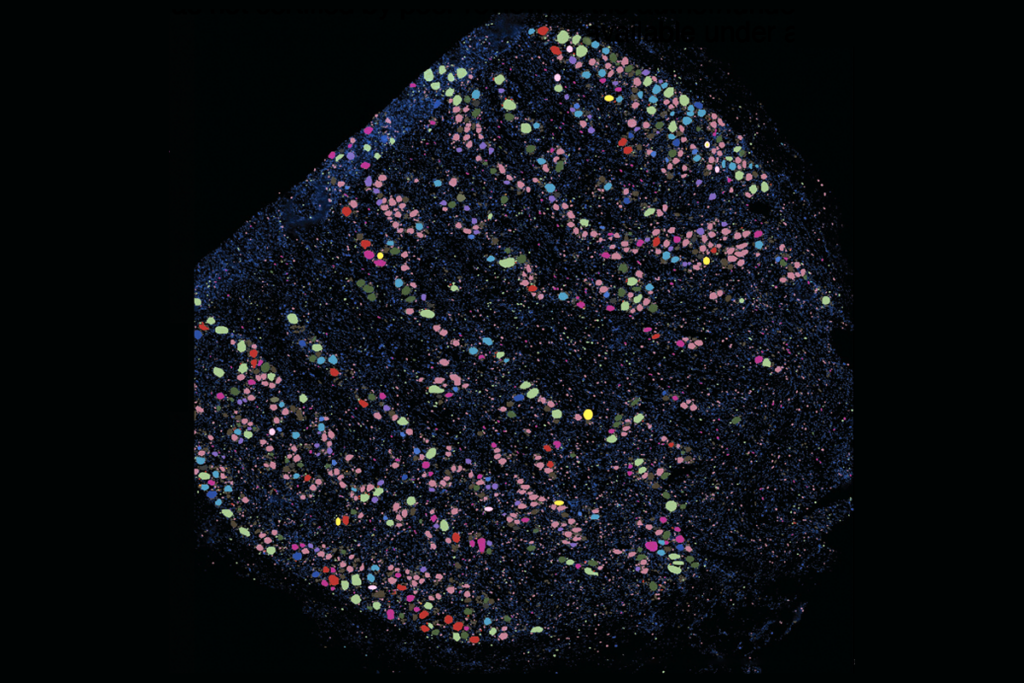

The atlas details the genetics, birth dates and gene-expression signatures of roughly 150 neuron subtypes in the dorsal horn of the mouse spinal cord.

A new atlas tracks the development of cells in the dorsal horn of the mouse spinal cord—and solves an enduring mystery of how the region’s specialized neurons acquire their assorted fates, according to a new study.

The developmental paths of ventral horn neurons are well established, but those of the dorsal horn, which have greater cellular heterogeneity, have remained a “black box,” says study investigator Ariel Levine, senior investigator in the Spinal Circuits and Plasticity Unit at the U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

“Our understanding of the dorsal horn has lagged very badly,” she says. “People have looked for 25 years to find what diversifies the dorsal horn.”

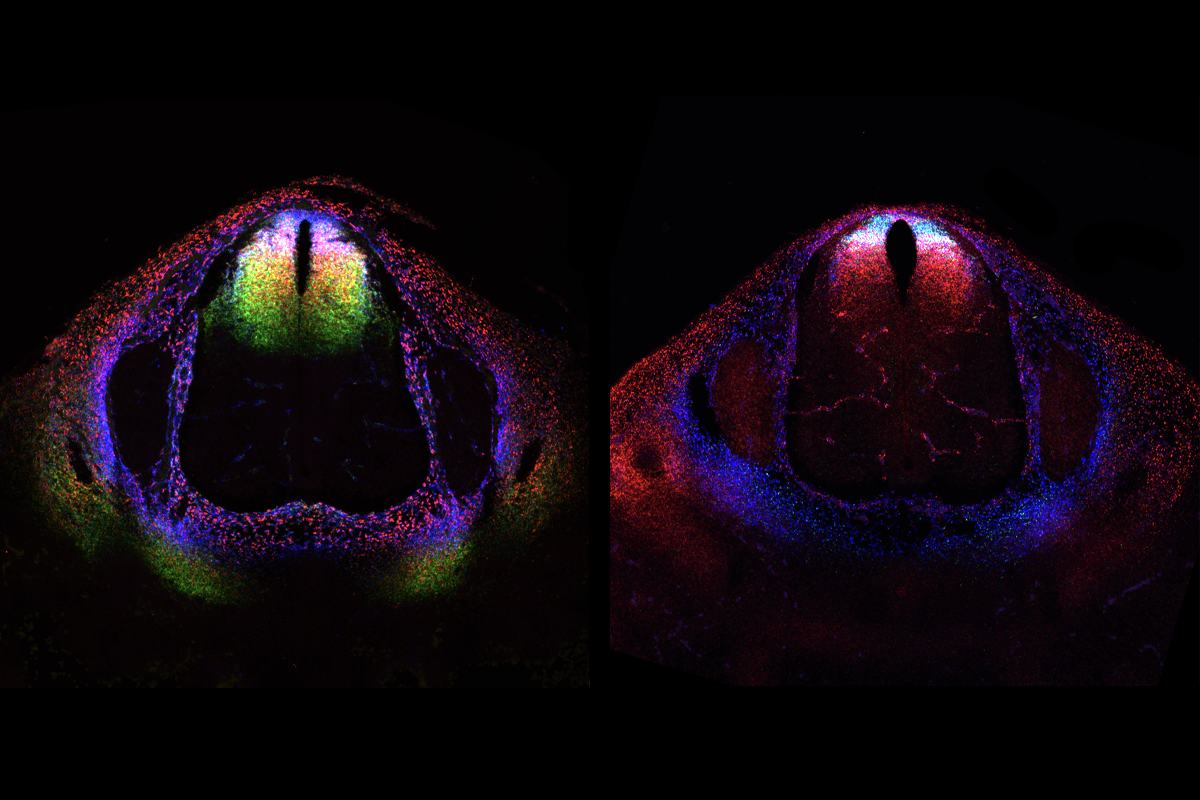

In adult mice, the dorsal horn’s neurons organize into six layers, which contribute differently to sensory processing, previous studies have shown. Superficial layers (I and II) process pain, temperature and itch, and deeper laminae (III to VI) process non-painful touch and proprioception. But despite these anatomical differences, researchers were unable to find clear molecular differences among cells in different laminae or unravel how this complex architecture arises from a relatively homogeneous pool of neural progenitors.

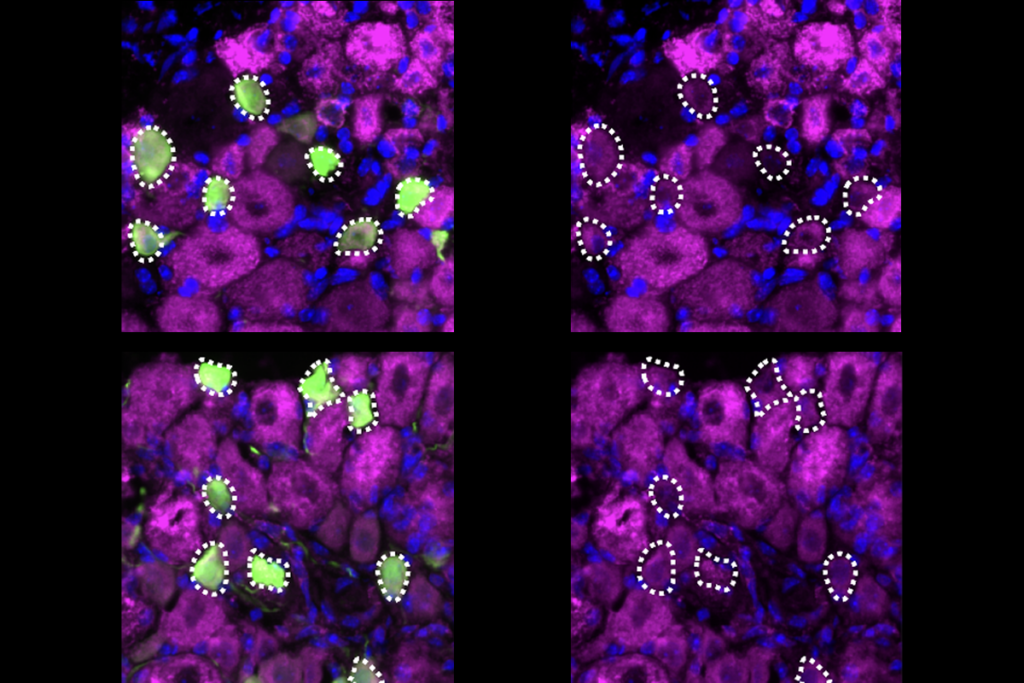

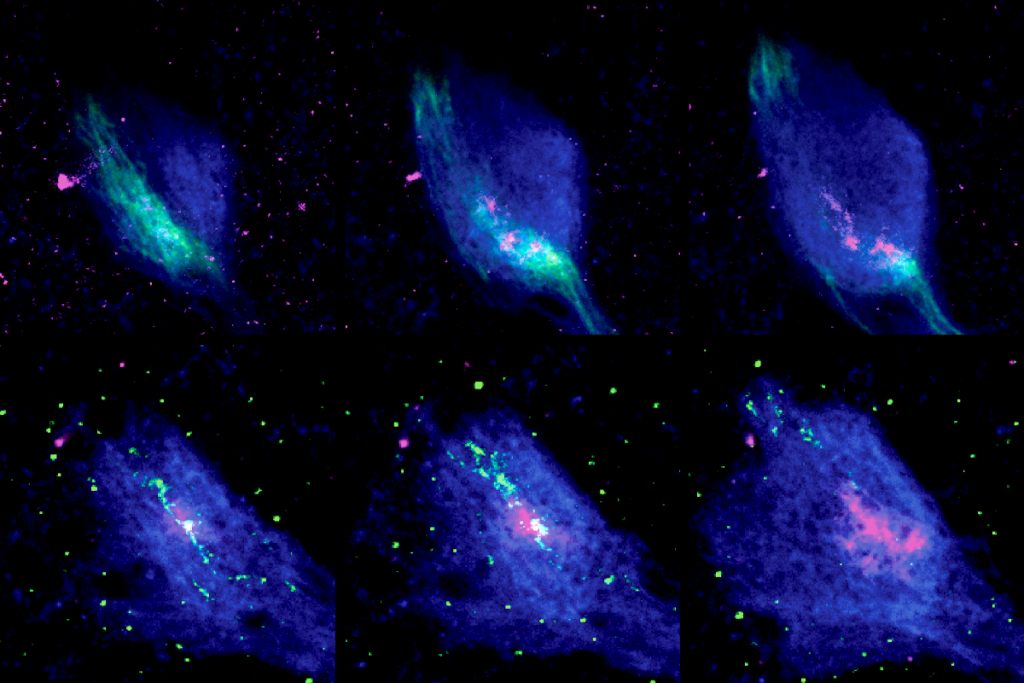

Dorsal horn progenitors diversify through six waves of neurogenesis over two days of embryonic development in mice, Levine and her team found using single-cell RNA sequencing, spatial transcriptomics and neuronal birth-dating. Each wave produces a different excitatory or inhibitory cell family, eventually resulting in the horn’s layered structure. The process generates about 150 molecularly distinct subtypes of neurons, revealing greater neuronal diversity than in previous classifications. The findings were published last month in Science.

“This study represents a substantial leap in our understanding of the development of the dorsal horn,” says Jennifer Dulin, associate professor of neurobiology at Texas A&M University, who was not involved in the work. The data could inform stem-cell-based therapies for spinal cord injury, she says. “This is something that, as a spinal cord injury researcher, illustrates the importance of basic research.”

D

To determine which neurons drive this chronotropic organization, Levine’s team created several lines of transgenic mice, each of which lacks one class of dorsal horn neurons: inhibitory, excitatory or sensory.

The loss of excitatory cells profoundly disrupted the spatial organization of other cells, the researchers found, which aligns with previous work in the cortex—indicating that the chronotopy of excitatory cells primarily determines dorsal horn organization. By contrast, the loss of inhibitory or sensory neurons preserved normal laminar organization.

But the six waves of neurogenesis the researchers identified didn’t quite explain the heterogeneity of neuronal classes present within each layer. The transcriptomic analysis, on the other hand, pinpointed a gradient in expression of Zic family transcription factors across the dorsal horn, which the team hypothesizes may explain the region’s myriad cell types.

The next step is to relate transcriptional signatures to functional properties of neurons in the spinal cord, says study investigator Brian Roome, who was a postdoctoral fellow in Levine’s lab during the study. “People have already found kernels of function associated with transcriptomic identity,” he says. The presence of transcriptional gradients means that there may be a vast array of functional differences among neurons based on their position in the spinal cord, as well as graded, or blended, specialization of cells in sensorimotor processing, he adds.

This work can also serve as a framework for future studies interrogating the circuitry of the dorsal horn, including how neurons connect to their downstream spinal, cortical or peripheral targets, says Helen Lai, associate professor of neuroscience at UT Southwestern Medical Center, who was not involved in the work.

The data could help future studies to elucidate the mechanisms of chronic pain, Levine says. In chronic pain states, “you start to get improper signaling between layers” in the dorsal horn, she adds, possibly because the formation of these neurons is dysregulated early in development.

But “neurons only compose a small fraction of the total cells in the spinal cord,” Ru-Rong Ji, professor of anesthesiology at Duke University, who was not involved in the study, wrote in an email to The Transmitter. Future studies are necessary to define the role of glial cells in dorsal horn development, particularly in pain processing and dysfunction, Ji says.

Levine and Roome say they plan to incorporate their data into a larger reference atlas for cell types in the mammalian spinal cord, which they hope to release in the next year. “If you put [this atlas] together with the existing datasets, you now have complete coverage over time,” Levine says.

Recommended reading

Waves of calcium activity dictate eye structure in flies

How developing neurons simplify their search for a synaptic mate

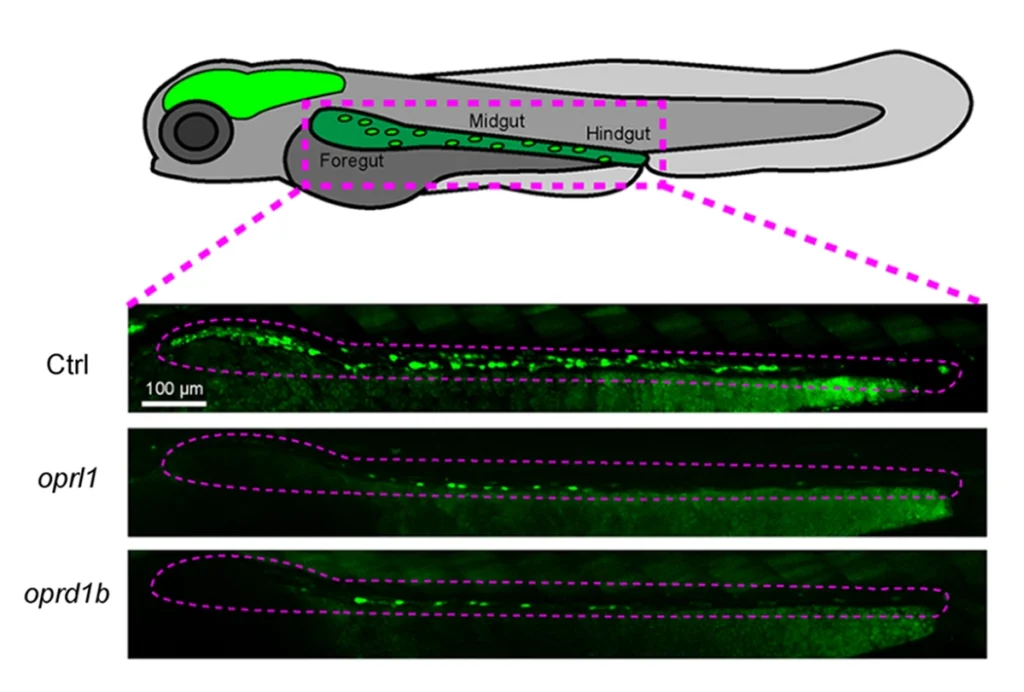

Opioid receptors may guide formation of gut nervous system in zebrafish

Explore more from The Transmitter

‘Unprecedented’ dorsal root ganglion atlas captures 22 types of human sensory neurons

Constellation of studies charts brain development, offers ‘dramatic revision’