The Trump administration has canceled two grants—among the slew of U.S. federal grants terminated at Harvard University in recent months—that together provided more than $4 million in funding to map more of the mouse brain than ever before.

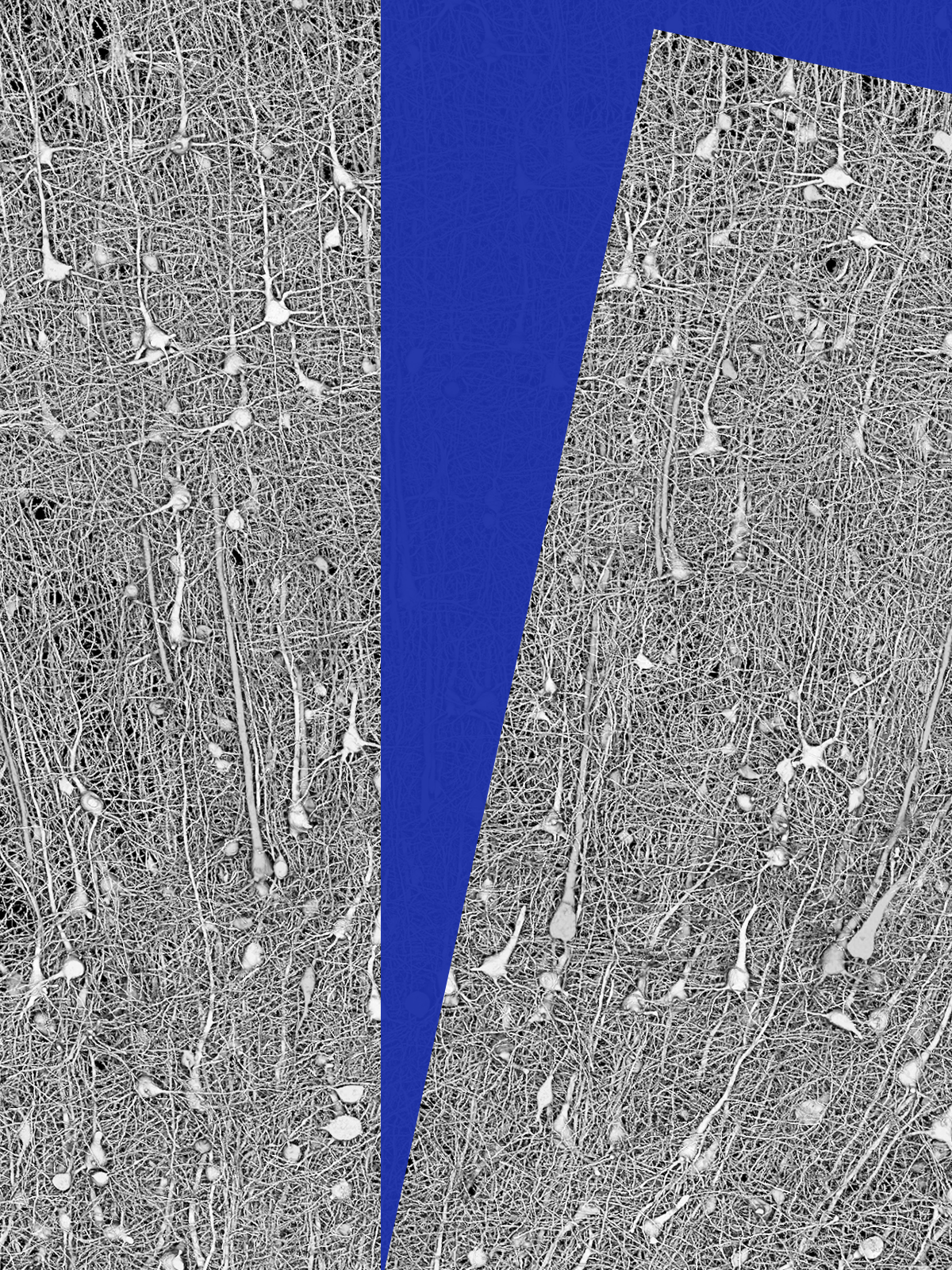

The grants were awarded by the National Institutes of Health’s BRAIN Initiative Connectivity Across Scales program, which launched in 2023 to scale up connectomic capabilities. They funded two Harvard-led teams to develop advanced electron microscopy tools to image each cell and synaptic connection within 10 cubic millimeters of mouse brain tissue—10 times the volume previously studied at that resolution. The data, collected from the animal’s hippocampal formation, would have been made freely available for other researchers to use in their own experiments, says Ila Fiete, professor of brain and cognitive sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who is one of the project investigators.

“This was a very ambitious project,” Fiete says. “It was supposed to be a technical proof of principle—a demonstration that shortly we can scale up to the whole-mouse-brain level.”

The tools the teams aim to develop could eventually aid in mapping the human brain connectome, says John Maunsell, professor of neurobiology at the University of Chicago, who is not involved with the work. “Getting this information is one of the things that was really thought important to come out of the BRAIN Initiative.”

Jeff Lichtman, professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard, is listed as the primary investigator on one of the canceled grants, which awarded $3.3 million last year. But investigators at other universities and institutions, including Princeton University, Cambridge University, the Allen Institute and Google, also bear responsibility for the work, says Sebastian Seung, professor of computer science and neuroscience at Princeton University and one of the project collaborators, who confirmed the cancellation. Another BRAIN Initiative grant, which awarded $1.1 million last year to Harvard University professor Aravinthan Samuel, has also been canceled, according to the online tracking site Grant Watch. Lichtman and Samuel did not respond to The Transmitter’s email requests for comment.

Hippocampal neurophysiologists and neuroscientists were awaiting the data to use in other experiments, Fiete says. And Harvard and Princeton were already in the process of building cutting-edge electron microscopes, she adds. “It’s certainly a blow to our immediate project and the personnel we would have had working on this project,” she says. “And then also, I think it’s a big blow for the field.”

T

he cancellations are part of the more than $3.2 billion in federal research grants and contracts for Harvard that the Trump administration has terminated or frozen since April in retaliation for the university’s purported failure “to confront the pervasive race discrimination and anti-Semitic harassment plaguing its campus,” according to a Department of Health and Human Services press release.And they come just as the field of connectomics has been hitting its stride, Seung says. This past October, the FlyWire Consortium, for example, which Seung co-leads, produced a full, open-access wiring diagram of the fruit fly’s brain, which has enabled researchers to better predict function from structure and understand the circuits involved in specific behaviors.

Researchers in the field had been hopeful that scaling up the mouse connectome would similarly spawn new discoveries, says James Eberwine, professor of pharmacology at the University of Pennsylvania, who is not involved with the canceled grants. “It’s going to be open source, not just in terms of the data that’s generated, but also in the techniques that were used to generate it.”

Harvard announced plans on 16 May to commit $250 million of its own funding to support research affected by the terminated grants. Beginning in July, researchers should first spend the majority of their non-federal funding from sources other than the university, the announcement instructs. After that, the school will work with principal investigators to cover up to 80 percent of lost grant funding through June 2026, the announcement states.

“We’re still hopeful we can get some bridge funding from the university, but that’s only going to last us for some limited amount of time,” Seung says. And in the meantime, the collaborators are looking into whether they can transfer the grant to a different institution, Fiete says.

Looking longer term, however, these cuts come on the heels of other recent disruptions to U.S. federal funding to neuroscience, including cuts to the National Institutes of Health and BRAIN Initiative budget, signaling broader problems for the field’s future, Maunsell says. “The bigger context, of course, is this is one lab, and things like this are happening to lots of neuroscience labs, medical research labs,” he says. “The real concern is this is just an instance of what’s been going on.”