Bad news for mouse poker players: Their facial movements offer “tells” about decision-making variables that the animals track without always acting on them, according to a study published today in Nature Neuroscience.

The findings indicate that “cognition is embodied in some surprising ways,” says study investigator Zachary Mainen, a researcher at the Champalimaud Center for the Unknown. And this motor activity holds promise as a noninvasive bellwether of cognitive patterns.

The study builds on mounting evidence that mouse facial expressions are not solely the result of a task’s motor demands and provides a “very clear” illustration of how this movement reflects cognitive processes, says Marieke Schölvinck, a researcher at the Ernst Strüngmann Institute for Neuroscience, who was not involved with the work.

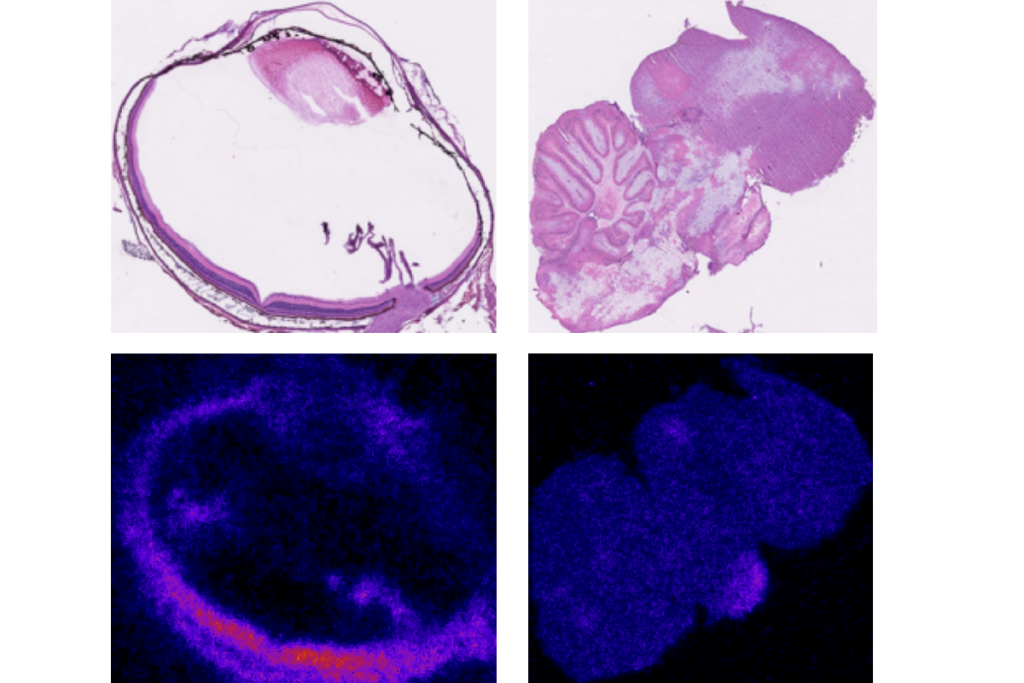

For years, mouse facial movements have mostly served as a way for researchers to gauge an animal’s pain levels. Now, however, machine-learning technology has made it possible to analyze this fine motor behavior in greater detail, says Schölvinck, who has investigated how facial expressions reflect inner states in mice and macaques.

Evidence that mouse facial expressions correspond to emotional states inspired the new analysis, according to Fanny Cazettes, who conducted the experiments as a postdoctoral researcher in Mainen’s lab. She says she wondered what other ways the “internal, private thoughts of animals” might manifest on their faces.

T

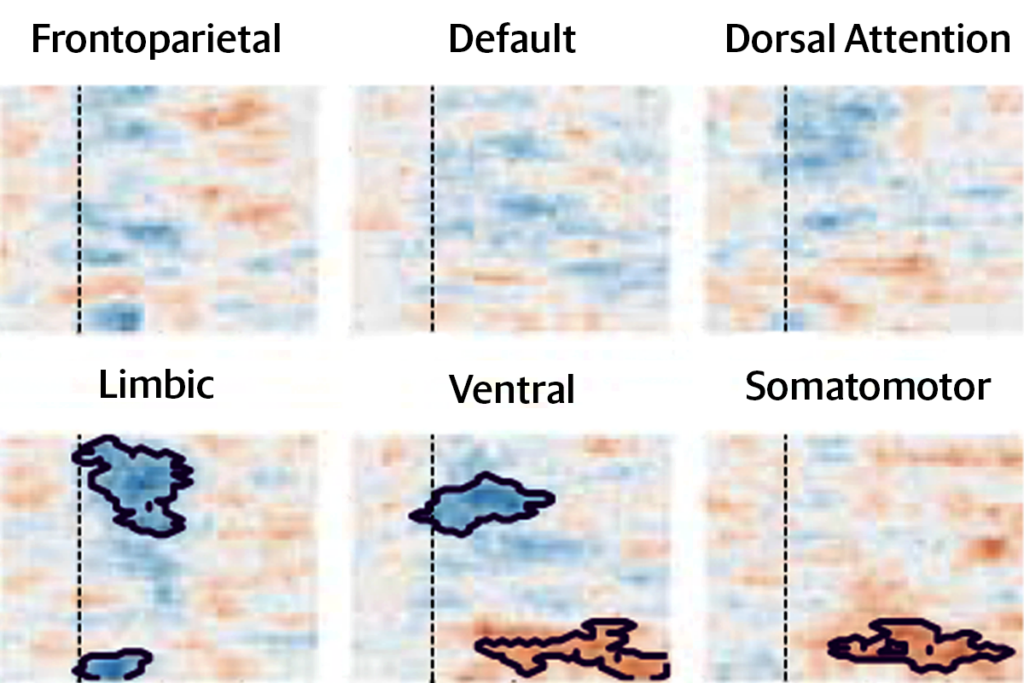

wo variables shape most mouse decisions over different foraging sites, the team found: the number of failures at a site (unrewarded licks from a source of sugar water) and the site’s perceived value (the difference between reward and failure).These decision variables underlie the three strategies mice use to choose between two foraging sites. Mice using a stimulus-based strategy make decisions according to a site’s value, whereas animals relying on an inference-based strategy judge the number of failures at their current foraging spot. Inference-based strategies are either impulsive or persistent, depending on an animal’s innate inclination to switch sites.

Even when mice employ one strategy, they still monitor other decision variables and can switch tactics, Cazettes reported in a 2023 paper. The secondary motor cortex (M2) orchestrates this tracking, according to electrophysiological recordings and optogenetic inactivation of cells in the region.

This internal variable tracking translates to differences in facial movements too subtle to detect by the human eye, the new study indicates. These expressions correlate with multiple latent decision variables, even if those variables are not part of a mouse’s current foraging strategy, according to a frame-by-frame video analysis that used a deep-learning algorithm called Facemap to predict neural activity from facial movements.

Activation of the M2 appears to drive motor activity and not the other way around, the researchers found. A model based on electrophysiological readouts was able to decode decision variables earlier than a model based on facial movement. Optogenetic inactivation of M2 produced immediate motor changes that hampered the facial movement model’s ability to predict decision variables.

The experiments demonstrate that M2 involvement is more than a byproduct of motions taken to execute a decision, says Alfonso Renart, who supervised the study alongside Mainen. Recent findings from other researchers also support a role for M2 activation in behavioral flexibility rather than motor task execution.