Psilocybin rewires specific mouse cortical networks in lasting ways

Neuronal activity induced by the psychedelic drug strengthens inputs from sensory brain areas and weakens cortico-cortical recurrent loops.

A single dose of psilocybin leads to widespread network-specific changes to cortical circuitry in mice, according to a new study published today in Cell.

The results help explain how psilocybin can bring about lasting changes in behavior, and they pinpoint “the neurons that are most affected,” says Andrea Gomez, assistant professor of molecular and cellular biology at the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved in the study.

Specifically, the psychedelic strengthens cortical inputs from sensory brain areas and weakens inputs into cortico-cortical recurrent loops. Overall, these network changes suggest that psychedelics reroute information in a way that enhances responses to the outside world and reduces rumination, says study investigator Alex Kwan, professor of biomedical engineering at Cornell University. “This study provides some more mechanistic insight for why the drug may be a good antidepressant.”

And the rewiring itself is not static, Kwan adds: “It can be influenced by manipulating neural activity” during psychedelic treatment.

With this locus of psychedelic-induced changes identified, researchers can unpack how these neuronal ensembles coordinate “to create particular percepts or particular cognitions,” Gomez says.

K

wan’s team focused on the mouse dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), which includes the anterior cingulate cortex—an important hub for the serotonin receptors that psilocybin targets.One dose of psilocybin increases dendritic spine growth in the medial prefrontal cortex of mice, an effect that lasts for at least a month, according to a 2021 study by Kwan’s team. And the treatment reduces the animals’ learned stress-related behaviors, but only if pyramidal tract neurons—one of the major types of excitatory neurons in the dmPFC—are active, Kwan’s group reported in April.

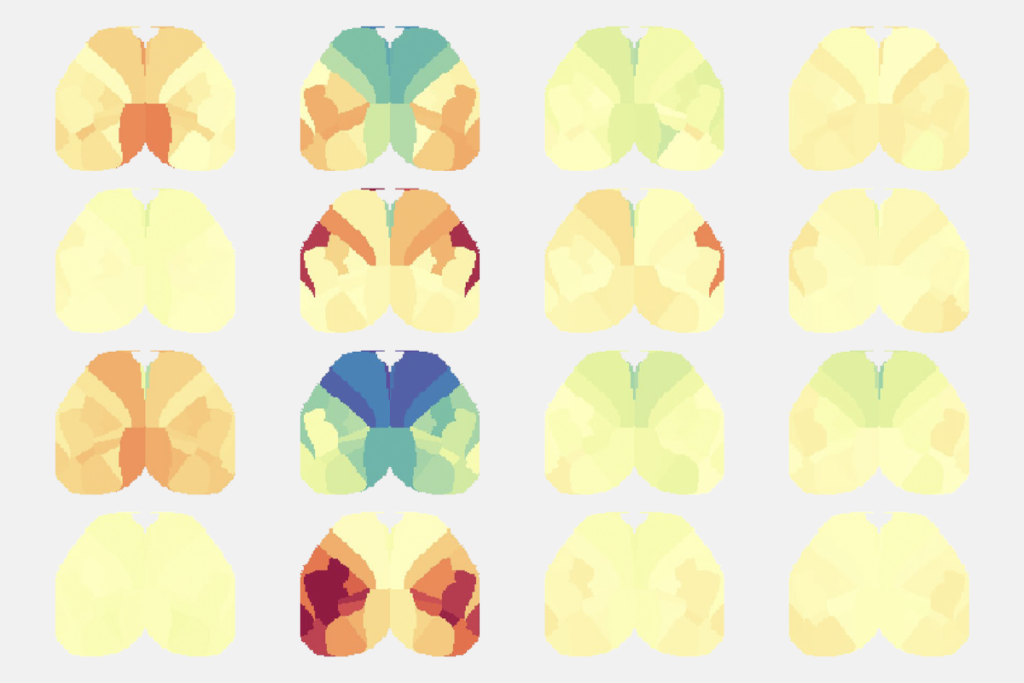

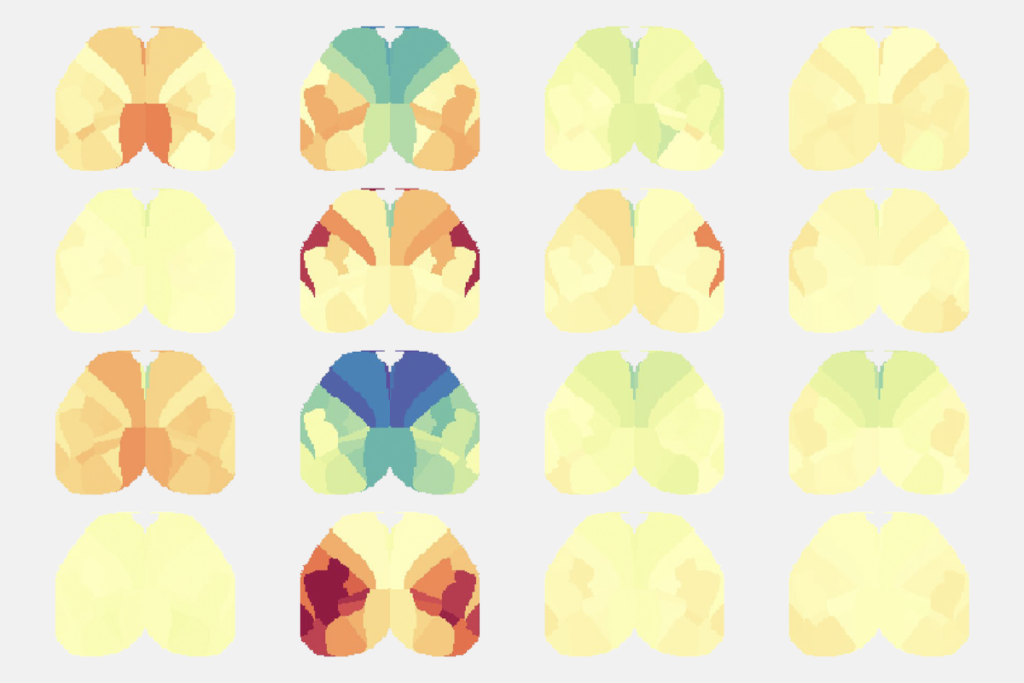

In the new study, the researchers used viral tracing methods and a 3D reference atlas of the mouse brain to map the inputs to pyramidal tract neurons and another major excitatory cortical cell type, the intratelencephalic neurons, in response to a single dose of psilocybin.

About a week after the treatment, pyramidal tract neurons in the mice had increased input from sensory regions compared with control mice, whereas projections from the insula and basolateral amygdala, which are important for emotional regulation, had decreased.

Intratelencephalic neuron inputs showed a different pattern of changes. These neurons are part of recurrent cortico-cortical loops and receive strong input from other sensory regions. Psilocybin weakened those inputs, the researchers found.

Neuronal activity during the psychedelic dose helps shape these long-term network changes, the study suggests. One of the regions whose input to pyramidal tract cells increased the most was the retrosplenial cortex. This is part of the mouse equivalent of the human default mode network, which “seems to intimately be involved in creating the sense of self,” says Joshua Siegel, assistant professor of psychiatry at NYU Langone Health, who was not involved in the study. Psychedelics disrupt this network to produce therapeutic effects, Siegel says.

Retrosplenial cortex projections to the anterior cingulate cortex ramped up their activity about 15 minutes after a psilocybin injection, the study reports. When the researchers chemogenetically silenced these projections before delivering psilocybin, however, they saw no increase in projections from the retrosplenial cortex to the anterior cingulate cortex, although inputs from other brain regions increased or decreased as before.

The findings show that how psychedelics rewire neural networks depends on their activity during the acute dosing, Siegel says. “And if you disrupt what’s going on during the acute dosing—in terms of neuronal firing, specifically—you can disrupt the lasting effect of the drug.” This result could mean that context and subjective experiences during psychedelic treatment are crucial for long-term therapeutic benefits, Siegel adds.

Using a combination of viruses to trace neuronal connections in living animals is tricky, because “you have to show that you’re doing what you want to do, and show that you’re not perturbing the system in a way that would confound your results,” says Melissa Herman, associate professor of pharmacology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was not involved in the study. This study does that well, Herman says, and is a particularly good example of using the access that model organisms provide to illuminate network-specific changes in a way that wouldn’t be possible in humans.

Kwan’s group is trying to understand what psychedelics “do to neurons and neural circuits,” to eventually “improve on the compounds and develop better drugs,” Kwan says. The new findings hint at a “possibility of shaping and steering that drug-evoked plasticity” by turning on or off particular circuits during the psychedelic experience to influence long-term brain changes, he says. He advises several pharmaceutical companies on their drug discovery efforts, including those involving psychedelic-related compounds, but he says that no companies paid for any part of the new study.

Recommended reading

Psychedelics research in rodents has a behavior problem

Psychedelics muddy fMRI results: Q&A with Adam Bauer and Jonah Padawer-Curry

Why we need basic science to better understand the neurobiology of psychedelics

Explore more from The Transmitter

Why we need basic science to better understand the neurobiology of psychedelics