When Nikolaus Plesnila entered the subarachnoid hemorrhage field about 20 years ago, most labs focused on what he calls “macrovasospasms”—the constriction of large cerebral vessels that begins days after the stroke occurs. Scientists studying macrovasospasms had pinned their hopes on endothelin receptor antagonists that tame these big vessels, says Plesnila, who leads the Laboratory of Experimental Stroke Research at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

When these drugs did not improve patient outcomes in a 2011 clinical trial, however, many researchers left the subarachnoid hemorrhage field, Plesnila says. He remained and continued his work on microvascular damage at earlier time points, while his colleague John H. Zhang at Loma Linda University codified the concept of early brain injury as damage that occurs within 72 hours of these rare strokes.

The concept of early brain injury was a valuable contribution to the subarachnoid hemorrhage field, Plesnila says, but he became wary of the “flood of papers” from the Loma Linda lab. Zhang is the most prolific author on early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage over the past two decades, according to a 2025 review.

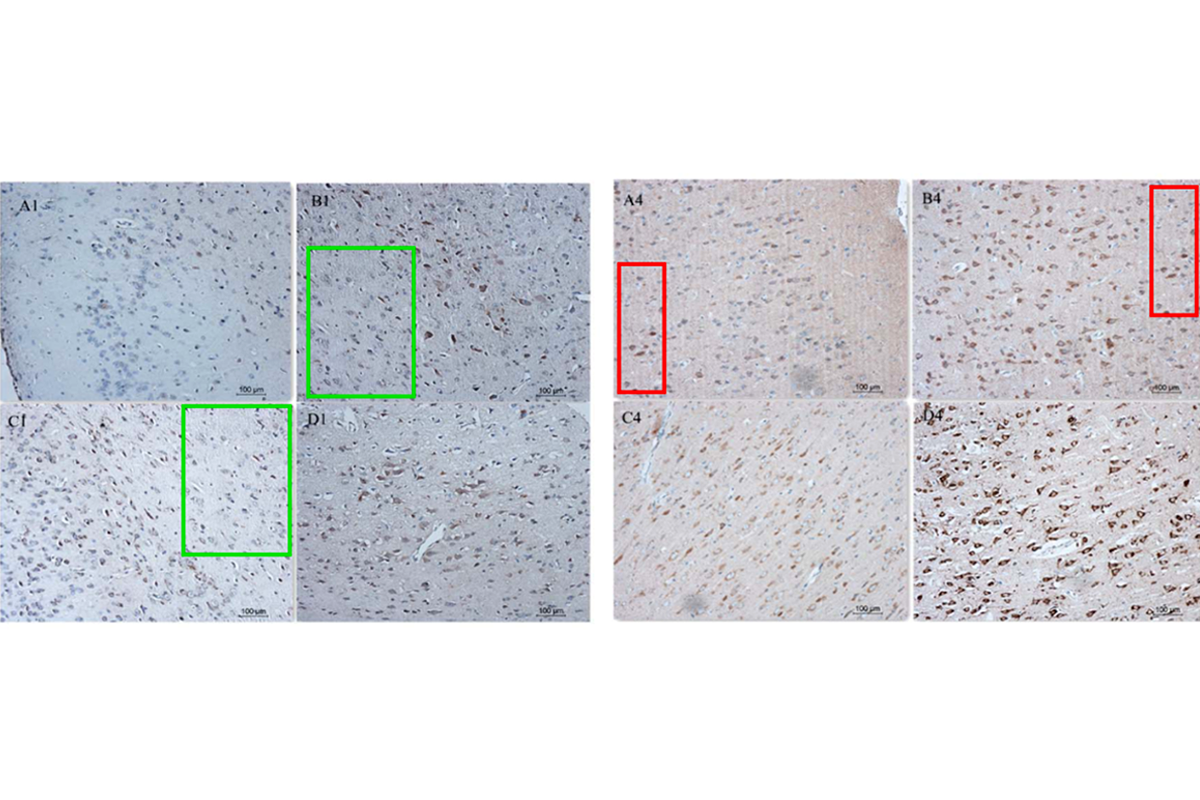

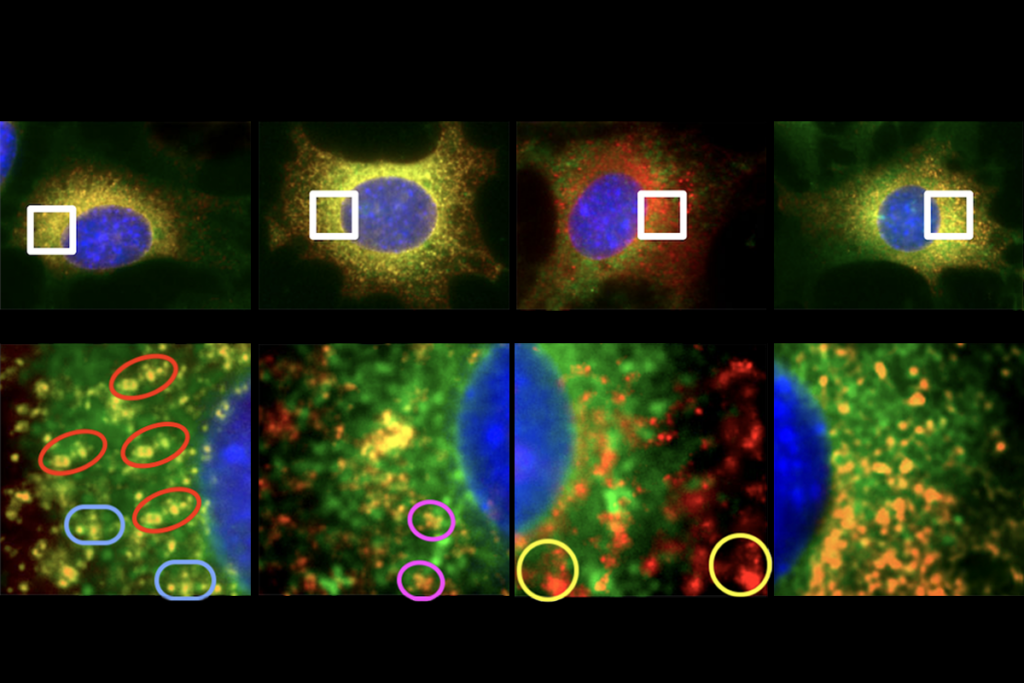

A meta-research article published today in PLOS Biology casts further doubt on the body of work that grew around Zhang’s prodigious output. Out of 608 papers about early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage that the authors analyzed, 243 show evidence of image duplication or manipulation. Zhang was listed as corresponding author on more than a tenth of these potentially problematic articles, per The Transmitter’s analysis of raw data that the meta-analysis’s authors made available to the public. (The corresponding author of the 2025 review tallying Zhang’s research output also authored multiple papers flagged by the analysis, including one that was corrected as a result.)

Not all of Zhang’s papers were deemed problematic, and he wasn’t the only author implicated in the new study. Nearly 88 percent of these papers have corresponding authors affiliated with Chinese research teams, though labs in other countries, including the United States and Japan, are also cited.

“The sheer amount of evidence that has problems will just steer a field into a sort of bog,” says Kim Wever, assistant professor on the meta-research team at Radboud University Medical Center in the Netherlands, who contributed to the meta-analysis.

The image integrity issues in these papers may have delayed progress around early brain injury after hemorrhage, says co-investigator and Radboud University Medical Center neurosurgery researcher René Aquarius. “Real research data may not have been published because people were discouraged by what was out there.”

A

quarius enlisted Wever to help conduct a systematic review of animal studies in his quest to identify potential treatments for early brain injury after a subarachnoid hemorrhage. Together they combed through the literature, looking for promising candidates to recommend for human experiments.The pair were initially pleased to find hundreds of papers supporting a vast range of interventions, Wever says. But then “we started to get a bit worried when we saw that all the interventions were tested only once, because we thought that was weird.”

So Aquarius and Wever began another kind of review, screening papers for evidence of image manipulation or duplication using an artificial-intelligence tool called ImageTwin. The problems the novice data sleuths found and confirmed by sight led to the retraction of nine papers from a research group at Kaohsiung Medical University, Retraction Watch reported in August 2024.

Publishers have not yet addressed most of the problematic subarachnoid hemorrhage papers from Zhang, but the volume of suspect articles he authored prompted Aquarius to examine Zhang’s work on other topics, Aquarius says. He shared concerns about 98 of Zhang’s papers on the post-publication research discussion platform PubPeer. Loma Linda University began an inquiry into Zhang’s work as a result, The Transmitter reported in June.

When The Transmitter reached out to Zhang about the new analysis from Aquarius and Wever, a Loma Linda University spokesperson reaffirmed that a review of Zhang’s research was ongoing and declined to comment further.

It seems likely that paper mills targeted the subarachnoid hemorrhage research field over the past decade, with an accelerating number of problematic papers starting in 2014, Aquarius and Wever say. The journal Bioengineered was delisted from Clarivate’s Web of Science in May after the review of subarachnoid hemorrhage papers spurred Aquarius to lead a separate analysis of the journal’s failure to address past paper mill activity.

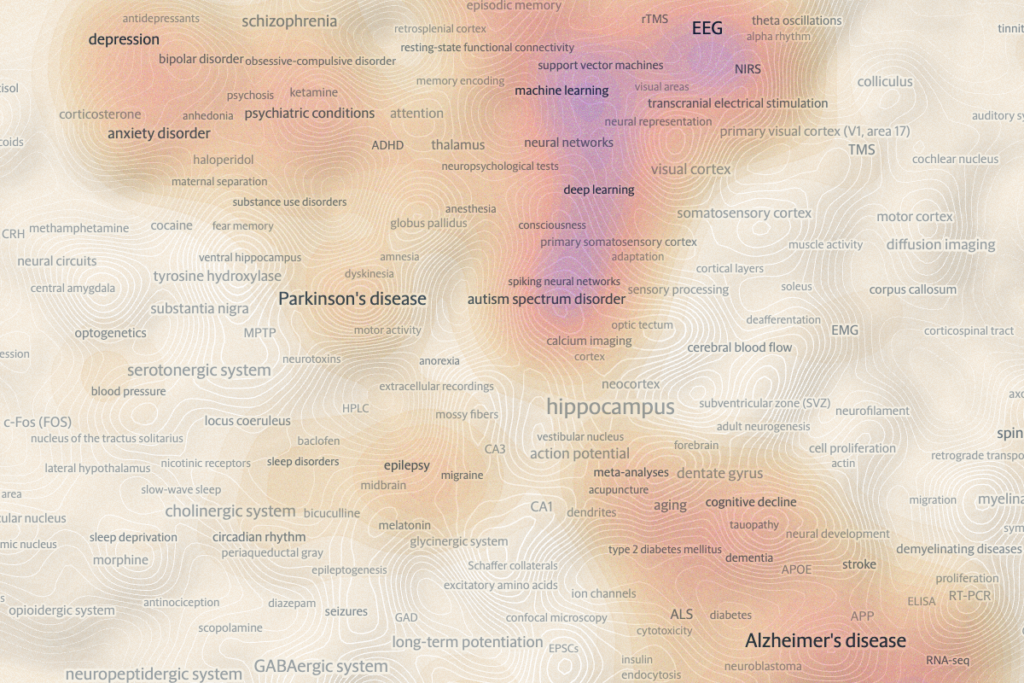

It’s possible that similar problems plague other fields, Aquarius and Wever say. They note that their investigation revealed that images they clocked as duplicated or manipulated were recycled in papers on subjects ranging from Alzheimer’s disease to lung cancer. The two sleuths say they have turned their focus to preclinical studies in other fields.

In the meantime, the duo say they have no immediate plans to revisit their initial project deriving human subarachnoid hemorrhage treatment candidates from animal studies. “We have no good ways to really identify which articles are now trustworthy and which are not,” Wever says. “I think we should not really base any recommendations for studies in patients on the evidence that we have found here.”

With additional reporting by science journalist Lori Youmshajekian for Retraction Watch, a nonprofit news outlet that covers research misconduct and related issues. Ivan Oransky, editor-in-chief of The Transmitter, is co-founder of Retraction Watch.