Autism study zooms in on five-gene strip on chromosome 16

Genetic analysis of one Belgian family with a history of autism has pinpointed a piece of DNA on chromosome 16, within a segment thought to be missing in about one percent of all cases of autism. The unpublished data was presented on Saturday at the World Congress of Psychiatric Genetics in San Diego.

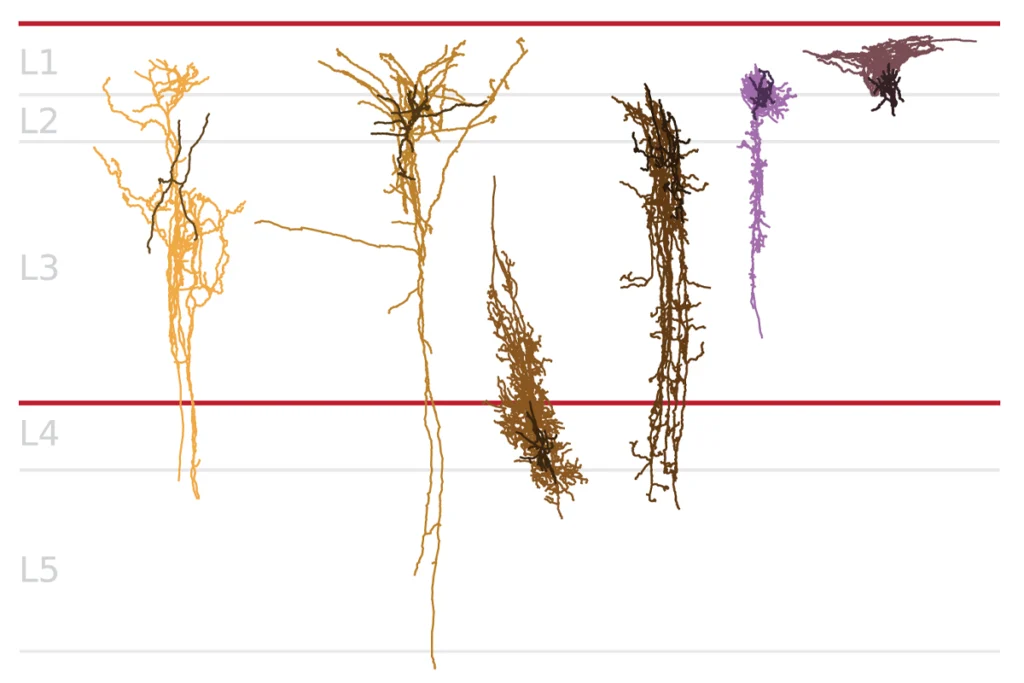

Narrow focus: Analysis of a Belgian family tree has identified a five-gene segment within the infamous 16p11.2 chromosomal region, thought to be involved in autism.

Genetic analysis of one Belgian family with a history of autism has pinpointed a piece of DNA on chromosome 16, within a segment thought to be missing in about one percent of all cases of autism. The unpublished data werepresented on Saturday at the World Congress of Psychiatric Genetics in San Diego.

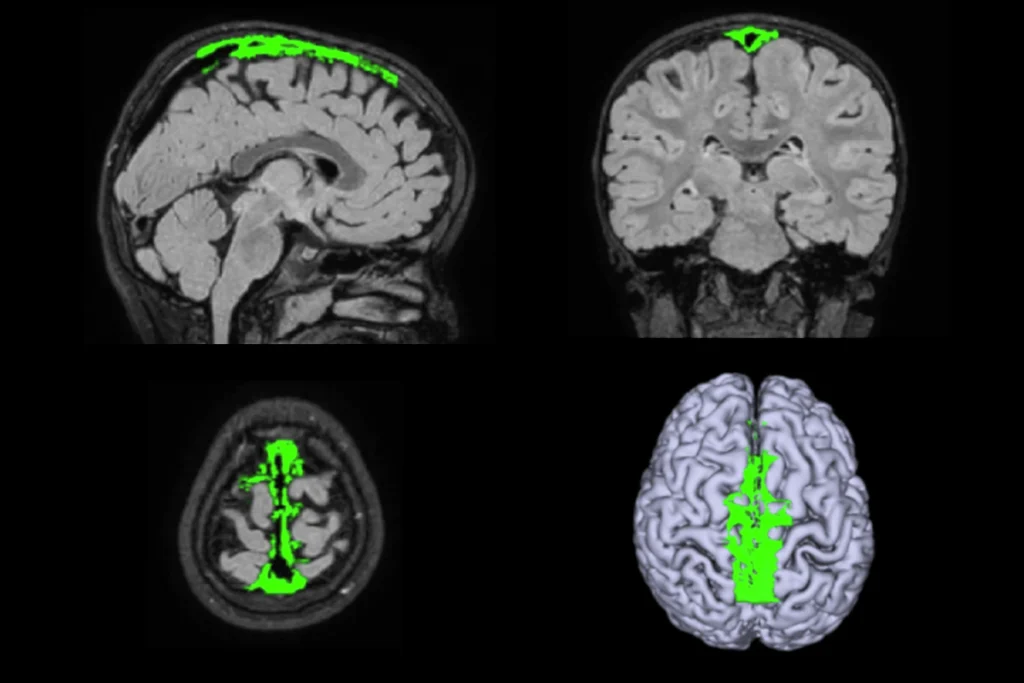

Three large studies to date have linked autism to a 25-gene-deletion on the short arm of chromosome 161,2,3. In the new work, scientists have identified a boy with autism who’s missing one copy of just five genes in this region. Two of the genes have biological roles in the brain that make them strong candidates for causing the disorder, the researchers say.

Since 2008, several independent groups have found that deletions of 16p11.2 crop up in people with autism up to 100 times more often than in healthy controls. The same deletion has also turned up in people with mental retardation and developmental delay, and a duplication of the region has been linked to schizophrenia.

Hilde Peeters and Koenraad Devriendt from University Hospital Leuven in Belgium screened 363 people with autism for deletions and duplications in one particular gene, SEZ6L2, in this infamous region. They found two people with deletions in the gene, but with a difference. The first has the typical 25-gene deletion spanning 600 kilobases. The second, a boy with normal intelligence, lacks the five-gene segment of only 115 kilobases.

The team then investigated three generations of the boy’s family, and found that his brother, his sister and a maternal aunt are all diagnosed with autism. His sister and aunt share the 16p microdeletion, but his brother does not.

The boy’s maternal uncle and maternal grandmother also carry the microdeletion. Neither has autism, but they — as well as the boy’s father — have unusually high scores on the Social Responsiveness Scale, a questionnaire that measures the severity of autism traits. An independent psychiatric examination found that the boy’s uncle shows additional deficits in non-verbal communication and impulse control.

The boy’s mother also carries the microdeletion, but does not have autism or autism-like traits, “making it quite complicated,” says An Crepel, a graduate student in Peeters and Devriendt’s lab who presented the data.

“Since there is an unaffected mother transmitting this deletion, it has to interact with other genetic and environmental factors in order to reach the disease state,” Crepel says, adding that this complicated interplay could also explain the unusual features in the mother’s brother.

Crepel says that the finding “is of great value to autism genetics” because it can help prioritize research on genes within the larger 16p11.2 region.

The newly identified microdeletion contains five genes: MVP, SEZ6L2, KCTD13, CDIPT and ASPHD1. Crepel highlighted two that are expressed in the brain and could potentially have high significance for the development of autism.

The first is SEZ6L2, or seizure related 6 homolog (mouse)-like 2. In February, geneticists from the University of Chicago reported that SEZ6L2 harbors a common variant associated with autism, although they couldn’t find the variant in a replication sample4.

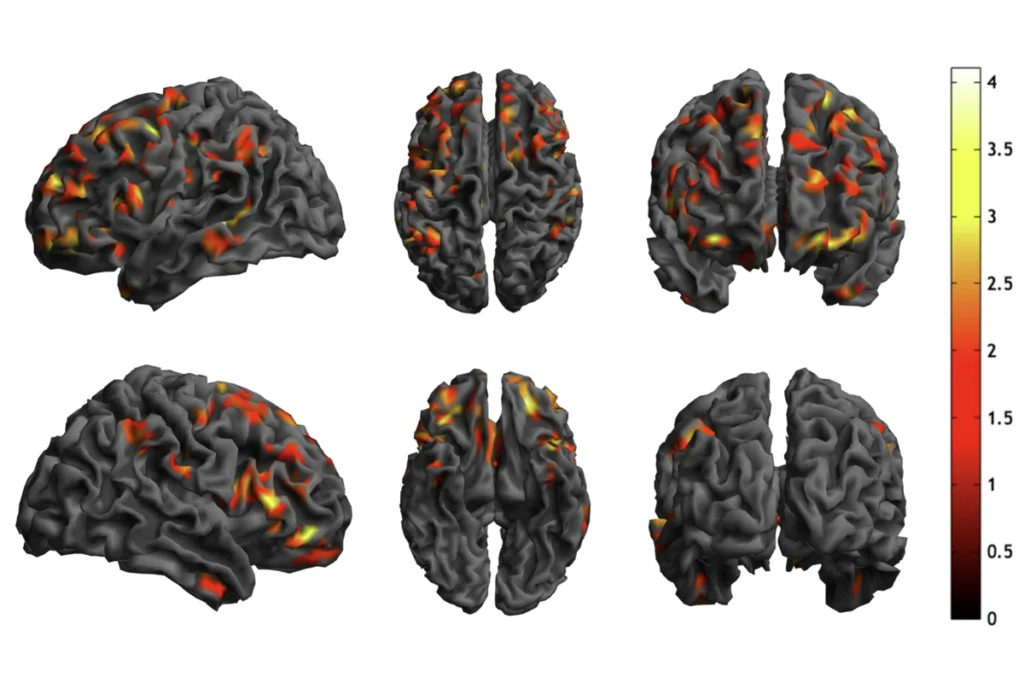

In the same report, the scientists found that the gene is highly expressed in the cortex, hippocampus, amygdala and thalamus of the fetal human brain — higher-order regions important for reasoning, memory and social behavior.

The second candidate gene encodes the major vault protein, MVP, which helps shuttle molecules between the nucleus and cytoplasm and may be involved in drug resistance. MVP interacts with the PTEN protein, a key player in cancer pathways that some studies have linked to tuberous sclerosis complex and autism.

References:

Recommended reading

Okur-Chung neurodevelopmental syndrome; excess CSF; autistic girls

New catalog charts familial ties from autism to 90 other conditions

Explore more from The Transmitter

Karen Adolph explains how we develop our ability to move through the world

Microglia’s pruning function called into question