Brain’s immune cells may explain sex bias in autism

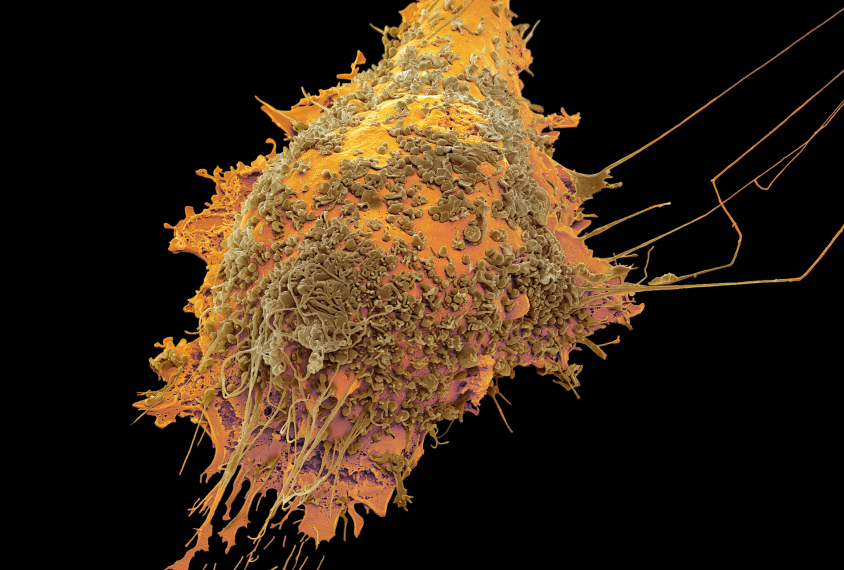

A boost in the activity of microglia, the brain’s immune cells, during gestation may predispose boys to autism.

A boost in the activity of microglia, the brain’s immune cells, during gestation may predispose boys to autism. The unpublished results were presented yesterday at the 2017 International Meeting for Autism Research in San Francisco, California.

Roughly four times as many boys as girls are diagnosed with autism. This may be because girls are somehow protected from autism — a popular theory — or because boys are predisposed to it.

Although the exact mechanism is still unclear, the new data suggest one way that male brains may become more susceptible to autism, says Donna Werling, who presented the findings. Werling is a postdoctoral associate in Stephan Sanders’ lab at the University of California, San Francisco.

A subset of genes in microglia are expressed at higher levels in male brains than in female brains during mid-fetal development, the researchers found. This is thought to be a key developmental period in autism.

Postmortem brains from people with autism also express microglia genes at higher levels than control brains do, according to published studies.

“Neurotypical male brains resemble the autistic brain with regard to microglial biology,” Werling says. “This specific aspect of male biology could put them one step closer to an autistic phenotype compared with females.”

Werling and her colleagues looked for sex differences in BrainSpan, a repository of gene expression from various stages in development. To their surprise, they found that gene expression in neurons does not differ significantly by sex.

“One of the messages of this is just how similar male and female brains seem to be, which is a good progressive message for the 21st century,” says Sanders.

Male microglia:

The sex differences in microglial genes are striking, however.

These cells are increasingly implicated in autism. They have long been known as the brain’s immune cells, but work in the past few years has shown that they also help shape early neuronal connections. Postmortem brains from people with autism may have more activated microglia than control brains do. And microglia from male mice respond more strongly to infection than do those from female mice, according to unpublished research presented at the 2016 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego, California.

“A lot of us are increasingly interested in the microglia story in autism,” says Jonathan Green, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom. “It’s one of those areas where there’s a lot of convergent evidence coming through. People are quite interested in this study for that reason.”

It is unclear how exactly microglia influence the sex ratio: Male brains may have more microglia, or more active ones, than female brains do. In either scenario, the cells in males would be expected to mount a stronger response to infection than cells in females.

Severe immune reaction during pregnancy is known to increase autism risk in the child. This immune effect may be amplified in males, Werling says. Because of their role in pruning synapses — the junctions between neurons — changes to microglia in early development may also have lasting effects on neuronal connections.

For more reports from the 2017 International Meeting for Autism Research, please click here.

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Explore more from The Transmitter

Snoozing dragons stir up ancient evidence of sleep’s dual nature