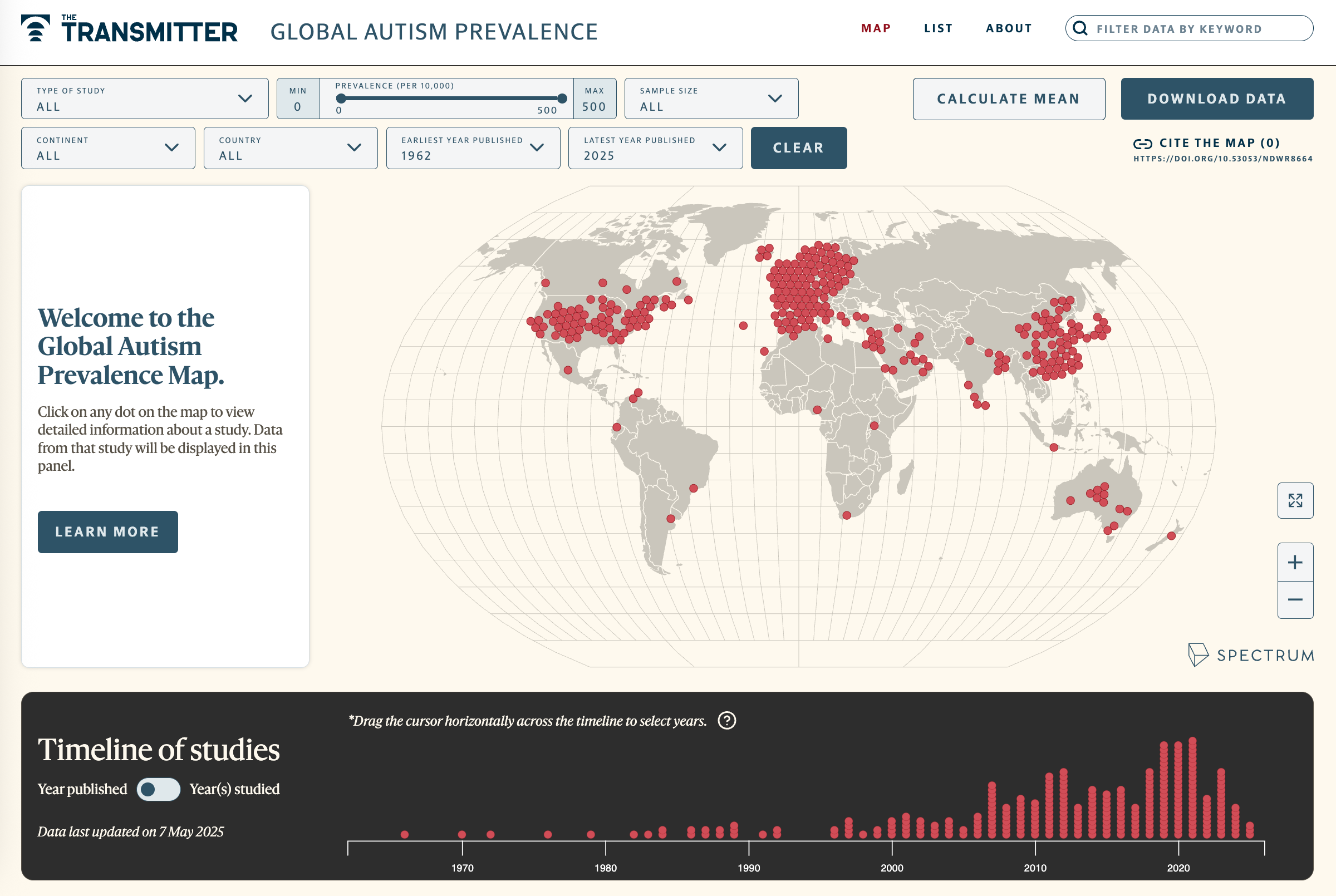

Autism prevalence has increased 60-fold in the past three decades, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A child in 1990 had a 0.05 percent likelihood of being diagnosed with autism, but a child in 2022 had a 3 percent likelihood. The CDC suggested that improved clinical detection may have contributed to the increase in autism prevalence, noting that California’s recorded autism prevalence of 6 percent in 4-year-olds in 2022 could be, in part, the result of increased detection by hundreds of California pediatricians who have been trained to screen for autism.

But the head of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., says he believes environmental factors—vaccines chief among them—have caused the increase in autism prevalence. As Axios and other news outlets reported, Kennedy said, “One of the things I think we need to move away from today is this ideology that this diagnosis, rather the relentless increases, are simply artifacts of better diagnoses, better recognition.”

National Institutes of Health Director Jay Bhattacharya subsequently announced that his agency hopes to have a call for proposals out by September, at which time researchers will be awarded grants to study autism causes. Kennedy presumably will want researchers to test his theory that the increase in autism is caused by environmental factors such as ultrasound scans or potential hazards such as food additives and pesticides.

Kennedy’s environmental exposures theory is shockingly naive because it ignores decades of study findings. This new research will also waste money better spent on evidence-based hypotheses. But at least a test of his theory may prove him wrong.

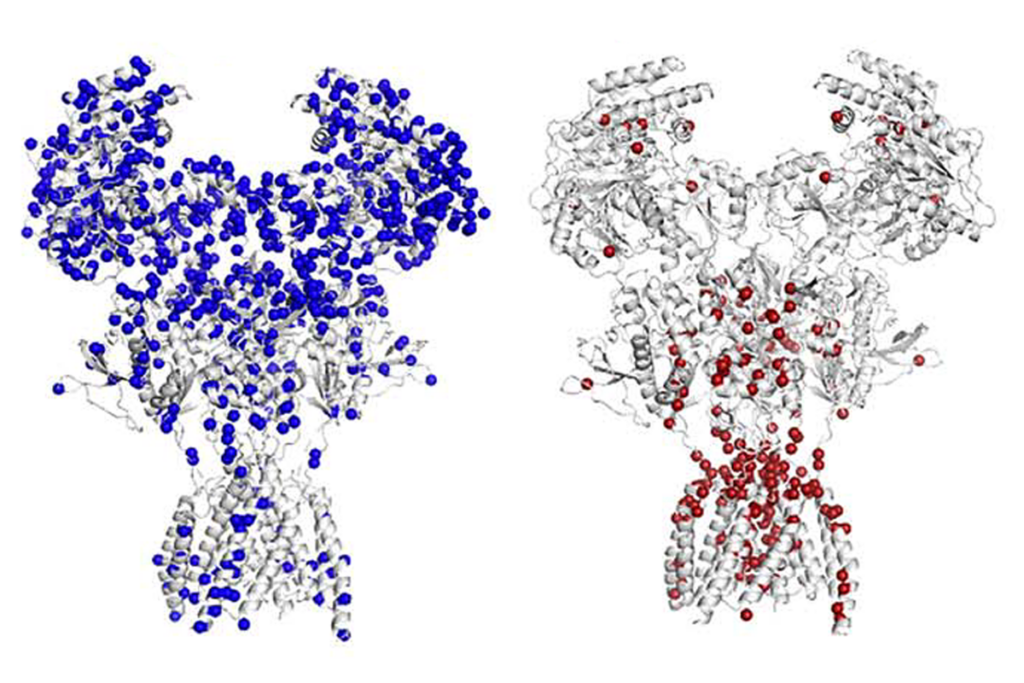

Kennedy’s proposed research is unlikely to find that ultrasound scans or food additives increase the likelihood of autism, as research has found no associations between autism and these exposures. In fact, environmental exposures account for less than 20 percent of autism cases; about 80 percent of cases are linked to genetic factors, as innumerable studies have proven. Furthermore, assigning likelihood is not simple. Some environmental exposures will result in autism only for people with specific genetic vulnerabilities.

Kennedy’s plan is also missing other potential environmental contributions to autism’s apparent rise. He has not discussed exploring maternal health, even though pregnant women’s health conditions can increase the likelihood that a child has autism. For example, children of women who take the drug valproate for epilepsy during pregnancy have a 4.42 percent higher likelihood of autism, and children of women with untreated infections or diabetes during pregnancy also have higher chances of having autism.

Improving maternal health can lower these chances. The MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine eliminated maternal rubella and, with it, fetal congenital rubella syndrome, the cause of at least 10 percent of autism in the 1960s and 1970s.

T

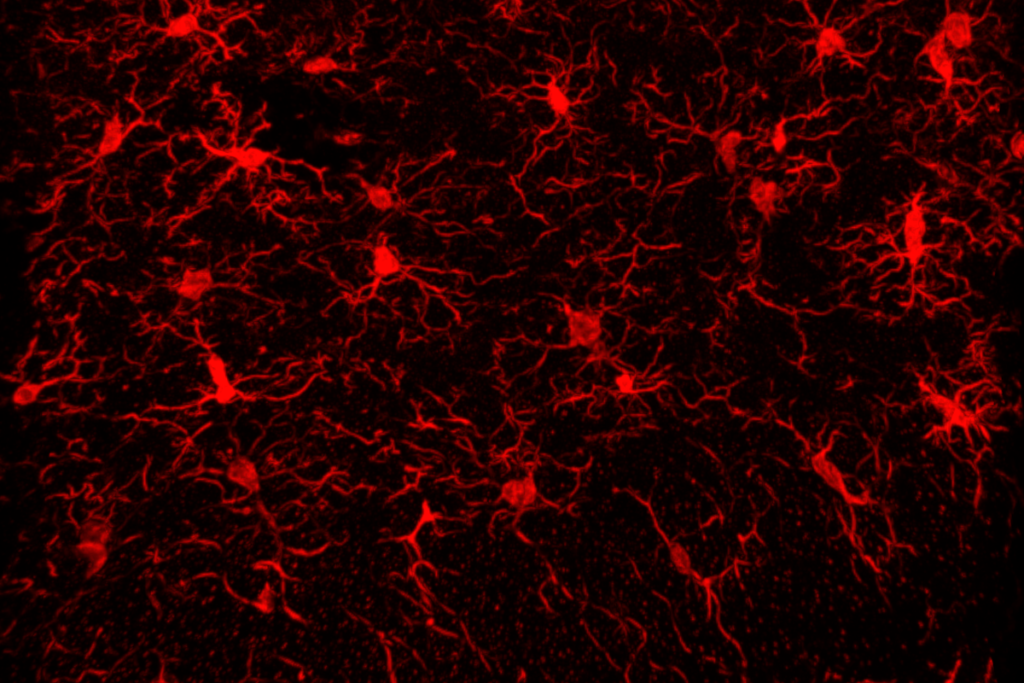

he latest scientific studies have built on previous evidence and explore the links between multiple gene variants, cognition, and behaviors associated with an autism diagnosis. Researchers are also studying the mechanisms of interaction between gene variants and environmental factors. More funding for these and similar research programs would advance our knowledge of the causes of autism.But these studies will not discover the cause (or causes) of the increase in autism. Both environmental factors and gene variants can contribute to autism, but it is unlikely that they have caused the increase in autism prevalence. For example, although gene variants are a significant cause of autism, there is a known stable rate of change in gene variants in humans. This low rate of change in gene variants cannot account for an increase in autism prevalence. And in the past 35 years, some environmental exposures have increased, but others have decreased through environmental regulations and improvements in health care. Despite this evidence, Kennedy believes there has been a massive increase in chemicals in the environment that has caused, in his words, an autism “epidemic.”

Most researchers and clinicians support the CDC’s claim that autism is becoming more prevalent because of increases in screening, early identification and awareness, along with diagnostic changes and improved access to services. But other neurodevelopmental diagnoses have also seen increases in screening, earlier identification, greater awareness, diagnostic changes and improved access to services, yet their prevalence has not increased 60-fold. For example, since 1990, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnoses have doubled, intellectual disability diagnoses have increased by a third, and schizophrenia diagnoses have not increased at all. I think it’s unlikely that there could be 30 times more undetected autism than undetected ADHD, and 46 times more undetected autism than undetected intellectual disability.

What else might be contributing to the increase in autism prevalence? Autism diagnostic criteria have changed, but they have not been continuously changing year over year for 35 years. However, clinical and public attention to autism has steadily increased. Perhaps that increased attention, coupled with the fact that the diagnostic boundary between autism and other neurodevelopmental diagnoses is fluid, has led to increased clinical sensitivity in recognizing more behaviors as diagnostic behaviors. We don’t know whether increasing clinical sensitivity is detecting a true increase in autism or is expanding the concept of autism.

The “gold standard” to establish an actual increase in autism would be finding a longitudinal increase in the number of people diagnosed using a tightly constrained set of behaviors and a set of reliable and valid autism biomarkers. But autism behavior patterns show immense heterogeneity, and research has not yet found a reliable set of biomarkers.

R

ight now, the lack of a definitive explanation for the increase in autism is a pressing concern for researchers and non-researchers alike, and Kennedy’s actions have heightened public concern. Unfortunately, misconceptions about autism abound. People who believe Kennedy’s unfounded claims may be unaware that there are genetic causes for autism. And people without personal knowledge of autism may be unaware that those with autism vary widely in their abilities. For example, Kennedy has claimed that people with autism will “never pay taxes, they’ll never hold a job, they’ll never play baseball, they’ll never write a poem, they’ll never go out on a date.” This is not true.Most troubling is that Kennedy’s beliefs may lead people to think that autism could be prevented by simply removing something from the air, food or water. We can only hope that Kennedy will someday realize that he should dissuade the public from the notion that there will be a prescription for the prevention of autism. Even better, Kennedy could plan a nationwide research program that follows the template of the Johns Hopkins GEARS (Combining Advances in Genomics and Environmental Science to Accelerate Actionable Research and Practice in ASD) research program that is working to identify environmental factors that, in conjunction with a genetic predisposition, increase the likelihood of having autism.