Clinical research: Language disorder distinct from autism

The families of children with specific language impairment do not have a history of autism, according to a study published 28 August in Genes, Brain and Behavior. The results bolster the theory that the two disorders have independent risk factors.

The families of children with specific language impairment (SLI) do not have a history of autism, according to a study published 28 August in Genes, Brain and Behavior1. The results bolster the theory that the two disorders have independent risk factors.

Language deficits associated with autism are difficult to distinguish from other language impairments. In particular, autism and SLI — a condition characterized by language problems but no other physical or cognitive deficits — are sometimes mistaken for each other in young children.

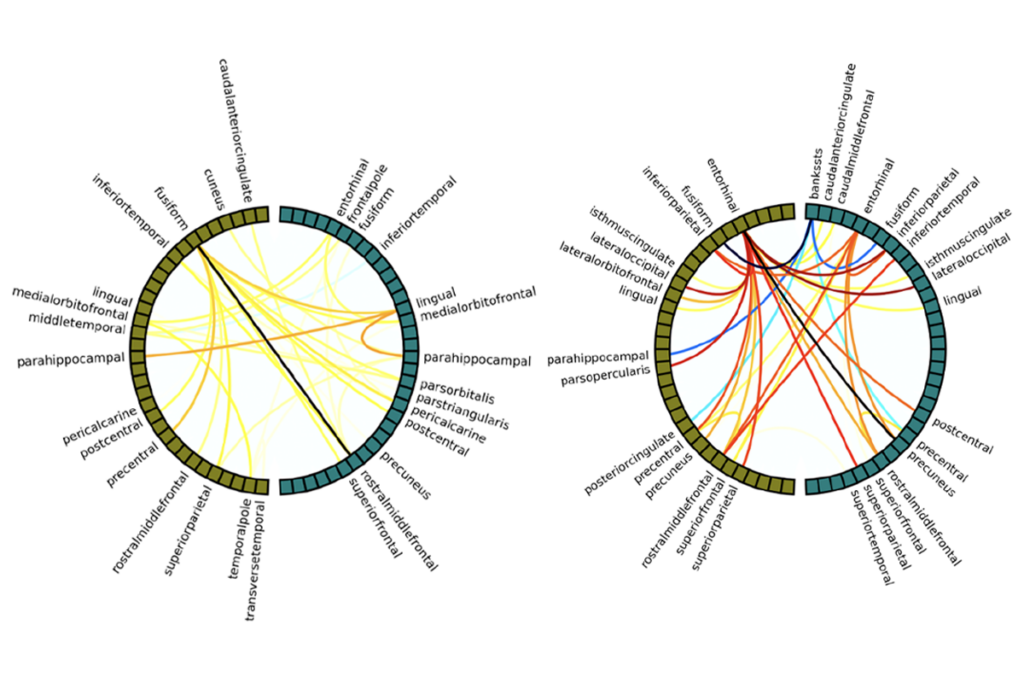

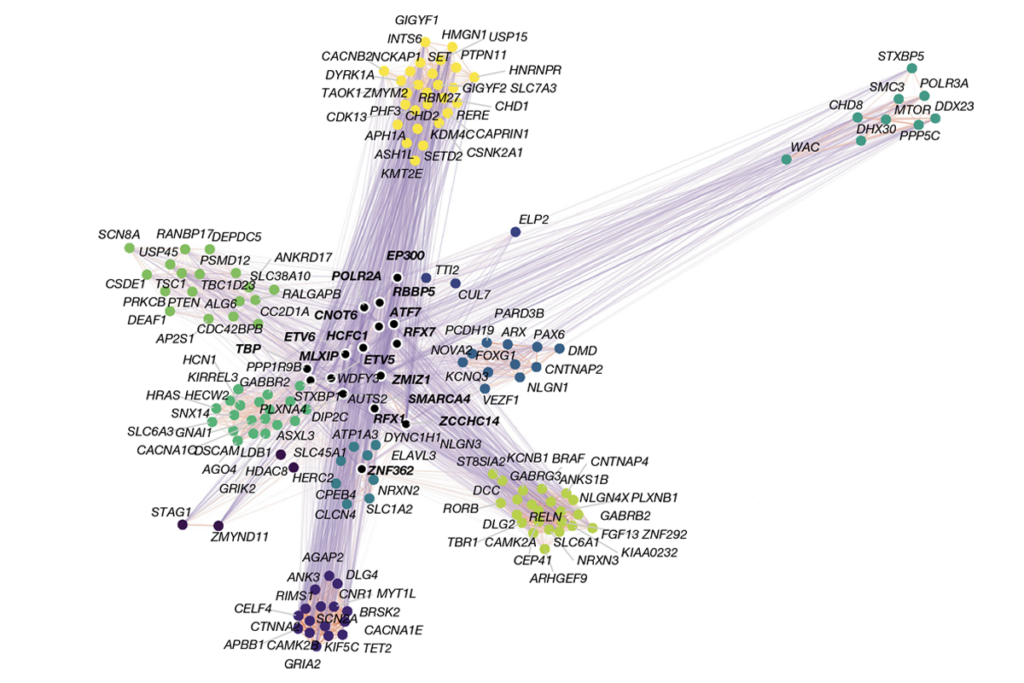

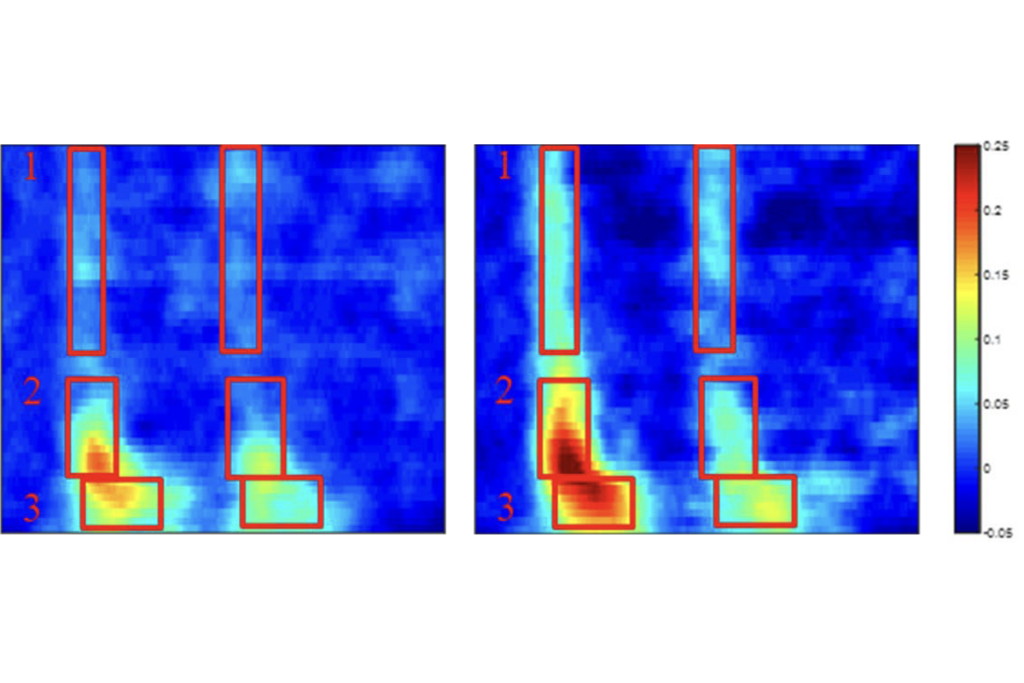

Several studies suggest that the language problems seen in the two disorders are distinct: Children with autism and those with SLI make different types of language-related errors and have distinct patterns of brain connectivity in language-related brain areas. Children with autism are also more likely than those with SLI to have broad communication problems, such as in using gestures.

In the new study, researchers looked at three generations of relatives of 59 children with SLI and 100 controls. They looked particularly at the prevalence in these families of language-related disorders, such as dyslexia, stuttering and hearing impairment, as well as autism, which is accompanied by language deficits, and Asperger syndrome, which is not.

Overall, parents of children with SLI are 37 times more likely than those of controls to have a language-related disorder, the study found. Of 118 parents of children with SLI, 27 have at least one of these disorders. In contrast, 14 of 200 parents of controls have at least one of the disorders.

Relatives of children with SLI are also more likely than controls to struggle with literacy. They are no more likely than controls to have a diagnosis of autism or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but are more likely to have problems with attention and hyperactivity that do not merit a diagnosis of ADHD.

References:

1: Kalnak N. et al. Genes Brain Behav. Epub ahead of print (2012) PubMed

Recommended reading

Organoid study reveals shared brain pathways across autism-linked variants

Sex bias in autism drops as age at diagnosis rises

Explore more from The Transmitter

New findings on Phelan-McDermid syndrome; and more