Cognition and behavior: Mind blindness in autism syndromes

Trouble with theory of mind, or the ability to infer what other people think or believe, is one of the most well-known deficits in autism. Two new studies show that theory of mind is also lacking in people with autism-related syndromes.

People with single-gene syndromes linked to autism lack the ability to infer others’ thoughts or feelings, according to two new studies published in the past few weeks.

Trouble with theory of mind, the ability to grasp others’ beliefs, is one of the most well-known deficits in autism. The new studies extend this deficit to velo-cardio-facial syndrome (VCFS) and fragile X syndrome. This sort of research may help researchers identify the genetic basis of the theory of mind deficit.

VCFS, caused by a deletion in chromosomal region 22q11.2, is characterized by heart defects, immune dysfunction and language delay. Some individuals with the syndrome are also diagnosed with schizophrenia or autism.

In a study published 7 September in Autism Research, researchers recruited 63 children and young adults with VCFS and 43 age-matched controls.

The participants took a computerized theory of mind test in which they watched animated triangles mimic human social interactions — for example, a mother cajoling a child or a boy mocking his teacher — and then described the scene. Researchers scored their responses according to whether they correctly identified the intentions and feelings of the characters.

Individuals with VCFS — with or without an autism diagnosis — have significant theory of mind impairments compared with controls, the study found.

A second report, published 20 August in Frontiers in Psychology, found theory of mind deficits in children who have both fragile X syndrome and autism. The syndrome, which stems from mutations in the FMR1 gene, is often accompanied by autism.

The study measured social cognition skills in 130 boys, all matched on vocabulary skills: 21 with fragile X syndrome only, 40 with fragile X and autism, 28 with autism, 21 with Down syndrome and 20 controls2.

The researchers measured theory of mind using a classic ‘false-belief task.’ This task often involves a skit in which one character believes something that’s not true — for example, that a ball is in a box when it’s really in a basket. The participants, even though they know where the ball is really located, must be able to infer what the character wrongly believes.

The researchers also tested how well the participants understand pragmatic language, which relies on subtle contextual information to convey meaning, and depends on theory of mind.

Children who have both fragile X and autism, and those who have classic autism have similar deficits in theory of mind and pragmatic language, performing poorly compared with the other three groups, the study found. In contrast, children with fragile X syndrome alone are no different from the control groups on these measures.

In the group of children with fragile X syndrome, the researchers also analyzed the nature of the FMR1 mutation. They found that greater levels of gene methylation — which shuts down proper expression of the gene and is linked to severe clinical impairments — are associated with lower scores on theory of mind and pragmatic language tests.

References:

Recommended reading

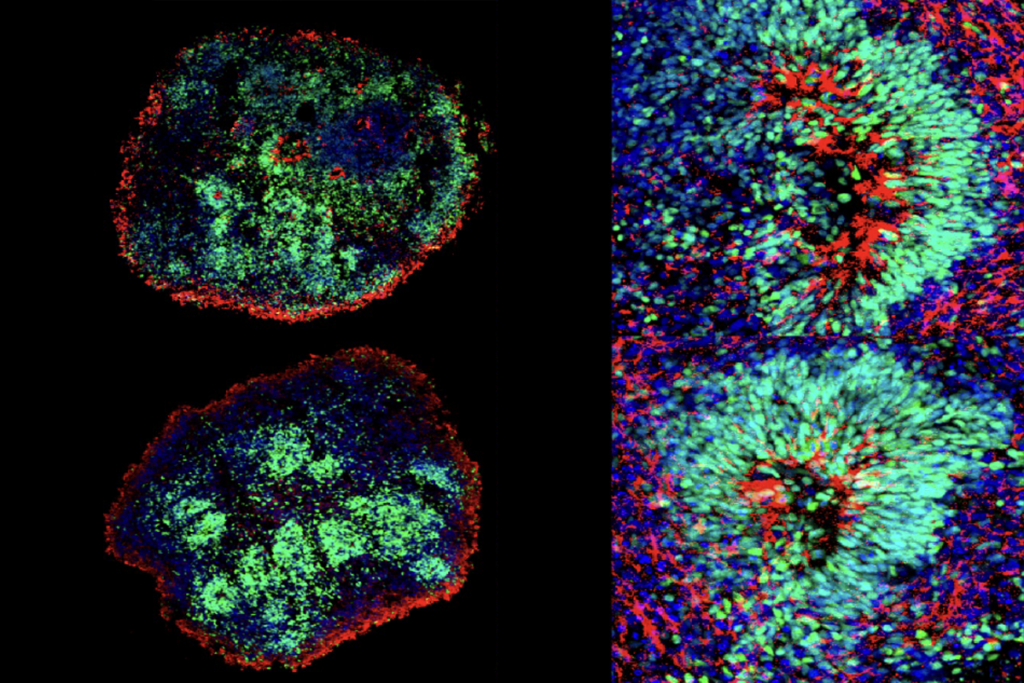

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

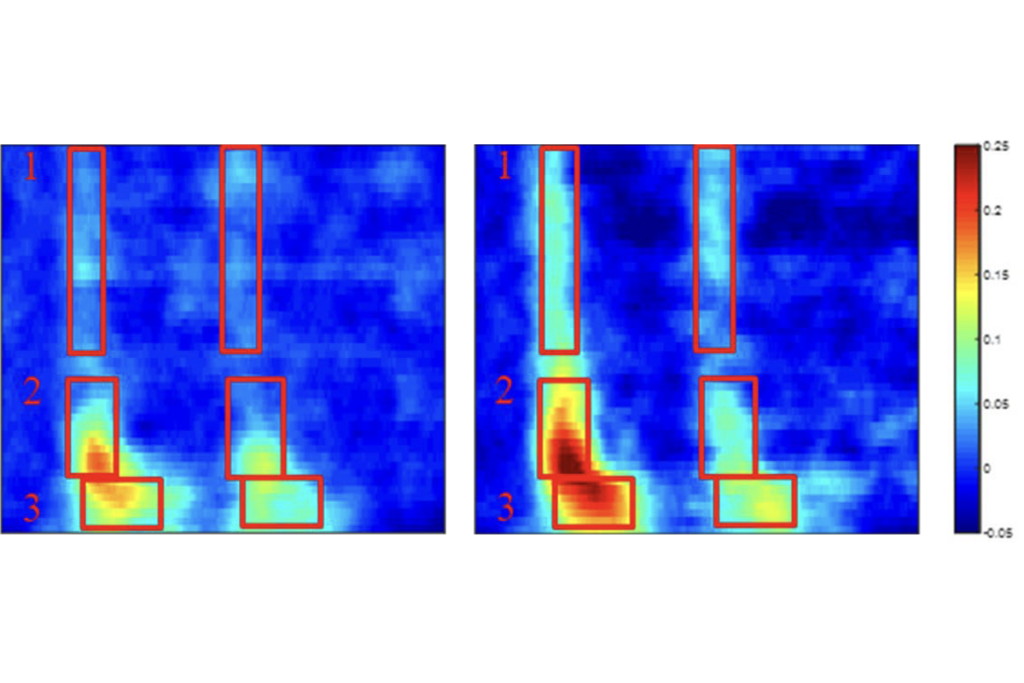

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

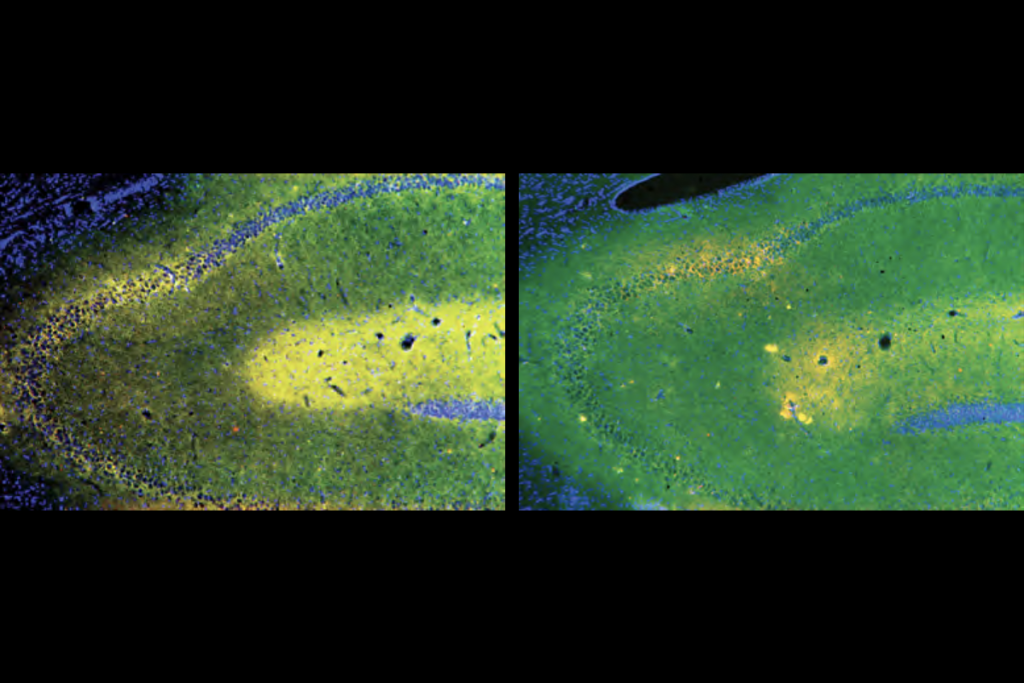

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Explore more from The Transmitter

Impaired sensory learning in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome; and more

New findings on Phelan-McDermid syndrome; and more