Cognition and behavior: Mouse models human Rett mutation

A mouse model of Rett syndrome that mimics a mutation seen in people shows many features of the disorder, such as hand clasping, according to a study published 27 November in Nature Neuroscience.

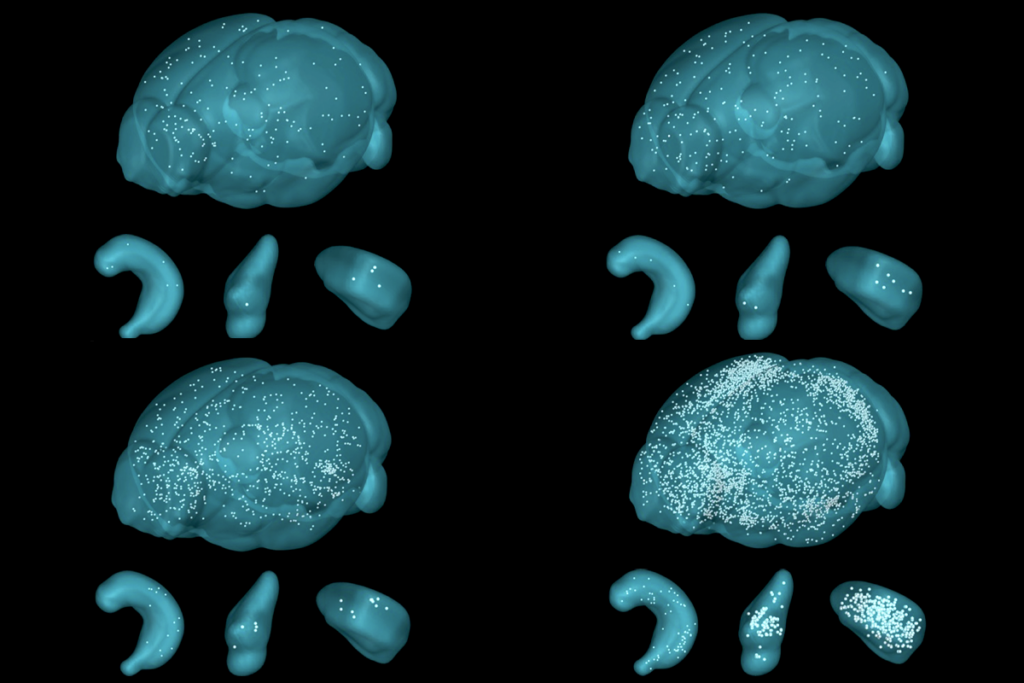

A mouse model of Rett syndrome that mimics a mutation seen in people has many of the behavioral features of the disorder, such as hand clasping, according to a study published 27 November in Nature Neuroscience1. The mice also have brain abnormalities that suggest a decrease in connectivity compared with controls.

Rett syndrome is an autism-related developmental disorder characterized by intellectual disability, small head size and repetitive hand movements. It is caused by a mutation in MeCP2, which functions as a master regulator, boosting and dampening the expression of thousands of other genes.

Most mouse models of Rett syndrome lack the MeCP2 gene. However, individuals with Rett syndrome typically have mutations that are alterations of single base pairs.

In the new study, researchers engineered mice to express MeCP2 with a mutation called T158A. This mutation is rarely found in people, but a similar T158M mutation is present in about ten percent of individuals with the disorder. Male and female mice with the T158A mutation weigh less and have smaller brains than controls do, the study found.

Like the knockout mice, these mutants start to show symptoms when they are 5 weeks old, comparable to the 6-18 month age range in the human disorder.

Compared with controls, the mutant mice have weak and delayed brain responses to sound as measured by electroencephalography. These alterations are present at 3 months of age, after the mice develop symptoms, but not before.

The mutant mice and the knockouts also both model the motor difficulties seen in Rett syndrome: They walk around less and fall off a rotating platform more often than controls do. They also clasp their hind limbs together, a behavior that is reminiscent of the hand movements seen in girls with Rett syndrome. Still, mice with the mutation have milder symptoms overall than those lacking MeCP2.

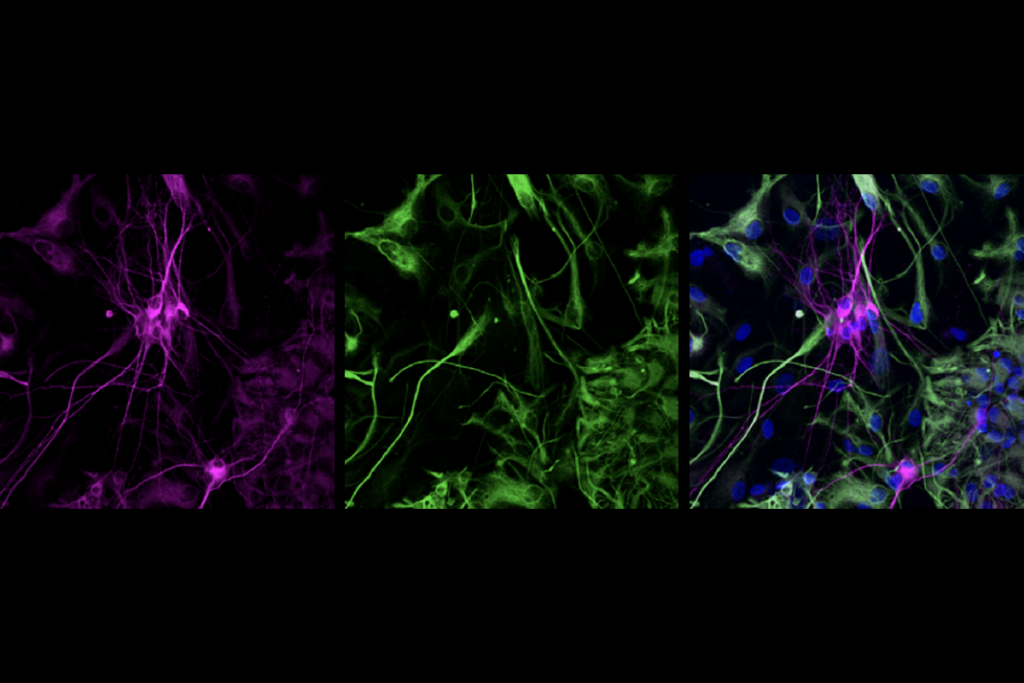

The mutant mice allowed the researchers to explore the effect of the human mutation at a molecular level, however.

For example, the MeCP2 mutation only partially impairs the function of the protein, the study found. The protein is less stable than it is in controls, and less of it is bound to DNA in the mouse brains. These observations suggest that compounds that improve the protein’s stability or its binding to DNA could help treat Rett syndrome, the researchers say.

Correction: This article has been modified from the original. The mutation has been corrected to T158A from T518A, and its prevalence in the population clarified.

References:

- Goffin D. et al. Nature Neurosci. Epub ahead of print (2011) PubMed

Recommended reading

Gene-activity map of developing brain reveals new clues about autism’s sex bias

Parsing phenotypes in people with shared autism-linked variants; and more

Boosting SCN2A expression reduces seizures in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Diving in with Nachum Ulanovsky