Gene-activity map of developing brain reveals new clues about autism’s sex bias

Boys and girls may be vulnerable to different genetic changes, which could help explain why the condition is more common in boys despite linked variants appearing more often in girls.

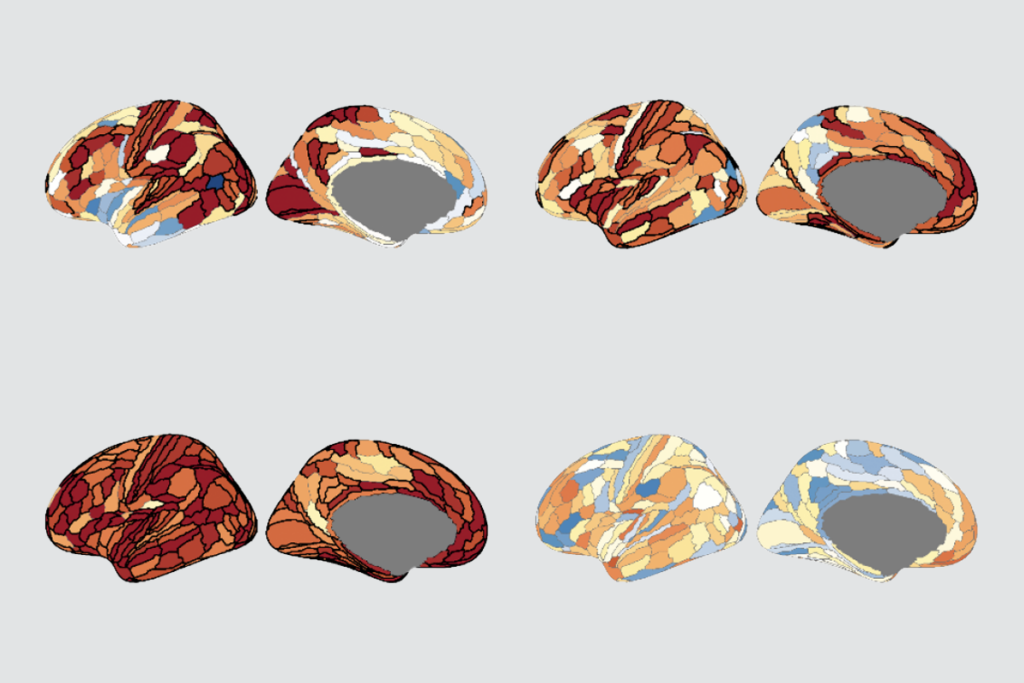

Male and female human fetuses show distinct patterns of gene activity and DNA regulation in the cerebral cortex, according to a new analysis of thousands of individual brain cells.

The study offers one of the most detailed maps to date of how such activity differs between boys and girls’ brains during the second trimester. It also compares sex differences in gene activity in fetuses with spontaneous genetic changes in autistic people, revealing clues as to how these de novo changes affect boys and girls.

“As the field evolves, this [work] will be a helpful reference” for exploring sex-related molecular differences in early brain development, says Matthew Oetjens, assistant professor of human genetics at Geisinger Medical Center, who was not involved in the study. Understanding these differences may help explain why certain neurodevelopmental conditions are more common in one sex than the other, he says.

Autism, for example, is diagnosed about four times more often in boys than in girls, but scientists are still trying to understand why. Theories include the possibility that boys are more vulnerable, girls are sometimes protected, or a combination of both.

“We know that autism … has a very strong genetic component. What is not known is how the genetic risk architecture intersects with any differences at the molecular level that might exist between male and female human brains,” says study investigator Tomasz Nowakowski, associate professor of neurological surgery, anatomy and psychiatry, and behavioral sciences at the University of California, San Francisco.

M

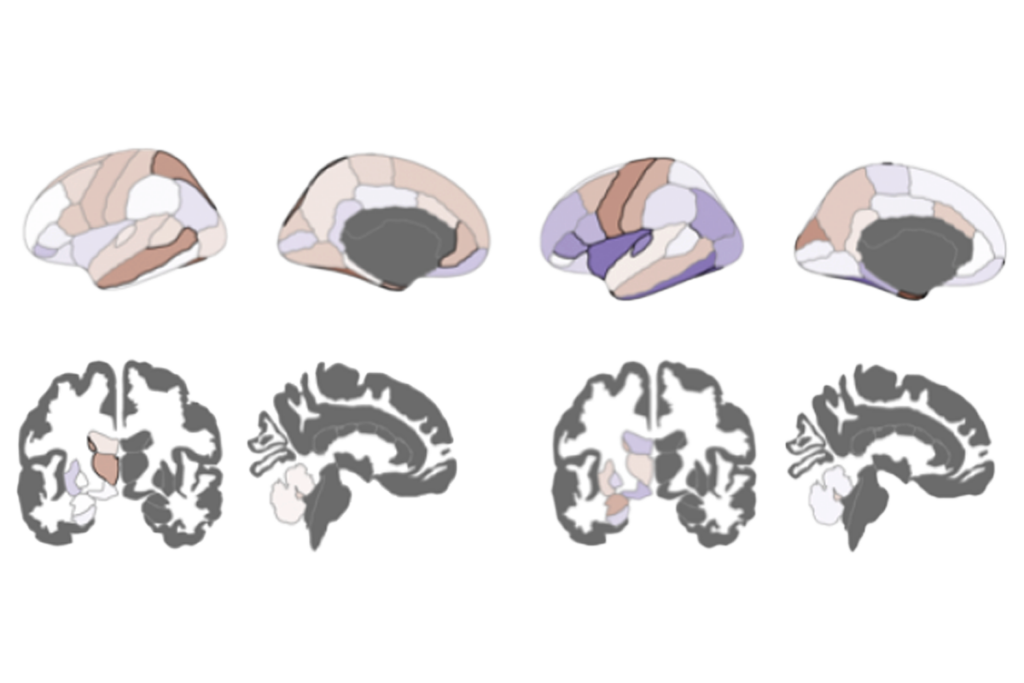

ore than 940 genes are expressed differently between the sexes, according to the new analysis of more than 38,000 brain cells from 21 female and 27 male mid-gestation fetuses. Most of these differentially expressed genes are more active in females.About 500 DNA regions are more accessible to proteins regulating gene expression in female brains, and a similar number of regions have greater accessibility in male brains, further analyses revealed. For females, these open regions were often inside genes; for males, they were usually farther away from genes, in regulatory areas. But differences in DNA accessibility rarely matched differences in gene activity.

Similarly, sex hormones such as estrogen and testosterone had little direct effect on differences in gene expression, the researchers found. The results challenge decades of assumptions by showing that, unlike in rodents, sex hormones may play only a minor role in shaping the developing human brain, says Bernard Mulvey, a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of Keri Martinowich at the Lieber Institute for Brain Development, who did not contribute to the work. “Everyone who has studied sex differences in rodents is going to drop their jaws.”

Nowakowski’s team also reanalyzed DNA data from nearly 62,000 children with autism or developmental delay, looking for spontaneous variants that could disrupt gene function. Only five female-biased genes, all on the X chromosome, showed a clear excess of variants in girls compared with boys, likely because variants in these genes are usually lethal in boys. Some autism-linked genes, they discovered, are expressed at higher levels in girls, which may provide a “buffer” against variants that disrupt gene function. The researchers posted their findings on bioRxiv in September.

“This paper has taken one of the most advanced attempts to ask, ‘What is the regulatory basis for sex differences in gene expression?’” says Armin Raznahan, chief of the Section on Developmental Neurogenomics at the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health, who wasn’t involved in the research but co-authored a recent preprint on sex differences in adult brains. His work found similar patterns: Although many sex-biased genes are found on the sex chromosomes, most are located elsewhere in the genome.

N

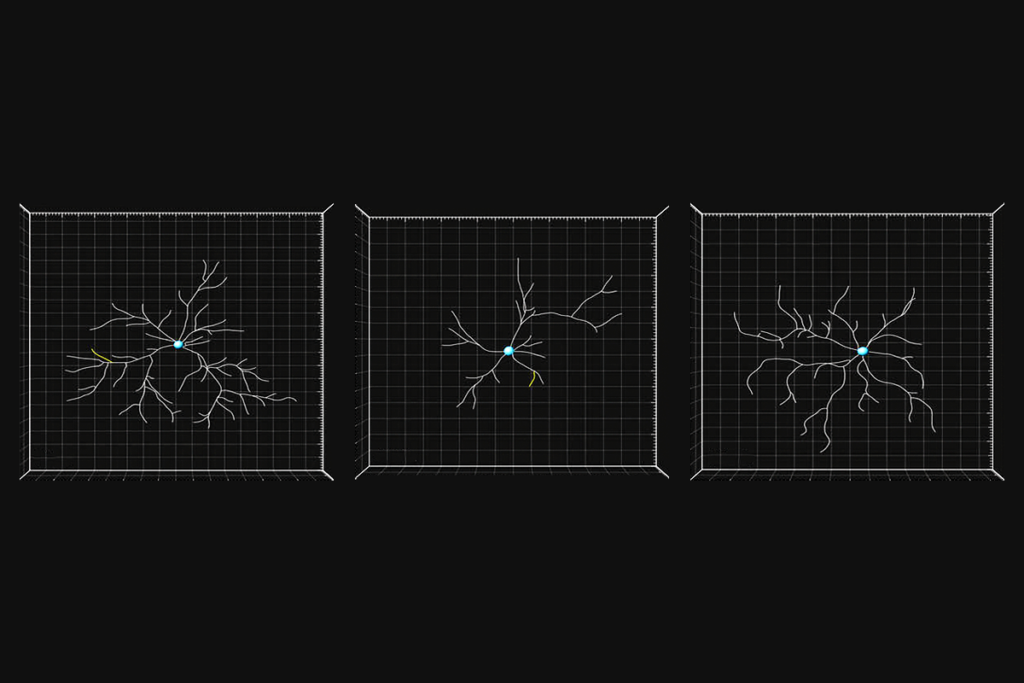

o clear link between genes showing sex-based differences in expression and changes in DNA accessibility or transcription factor activity appeared in Nowakowski’s study, a finding Raznahan described as one of the most striking.To uncover the regulatory mechanisms driving these differences, he adds, future research will need to consider larger sample sizes, more brain regions and a broader range of developmental stages. It will also require combining observational studies with experimental approaches so that researchers can manipulate the genome or environmental factors such as sex hormones, he says.

By linking fetal-brain-development data with large genetic studies on autism, the work suggests that girls may be more affected by changes to DNA regions that code for proteins, whereas boys may be more affected by variants in noncoding regions that regulate gene expression.

This difference could explain why autism is more common in boys, but genetic testing finds more coding variants in girls, says Aaron Besterman, associate clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved in the work. “One contributing factor to the elevated prevalence [of autism in boys] is that there may be a lot of genetic risk for autism in regions of the genome that we historically have not looked closely at.”

In this sense, the findings could help clinicians make better guesses about the impact of certain genetic variants; for example, a noncoding variant in a boy may be more likely to contribute to a specific neurodevelopmental condition than a coding variant on the child’s X chromosome, Mulvey says.

The new study also supports the idea of a ‘female protective effect,’ in which girls need more genetic or environmental changes than boys to develop neurodevelopmental conditions, Oetjens says. But understanding molecular differences in the brains of boys and girls with autism will require much more work, he says. “I don’t think there’s a smoking gun.”

Recommended reading

Sex bias in autism drops as age at diagnosis rises

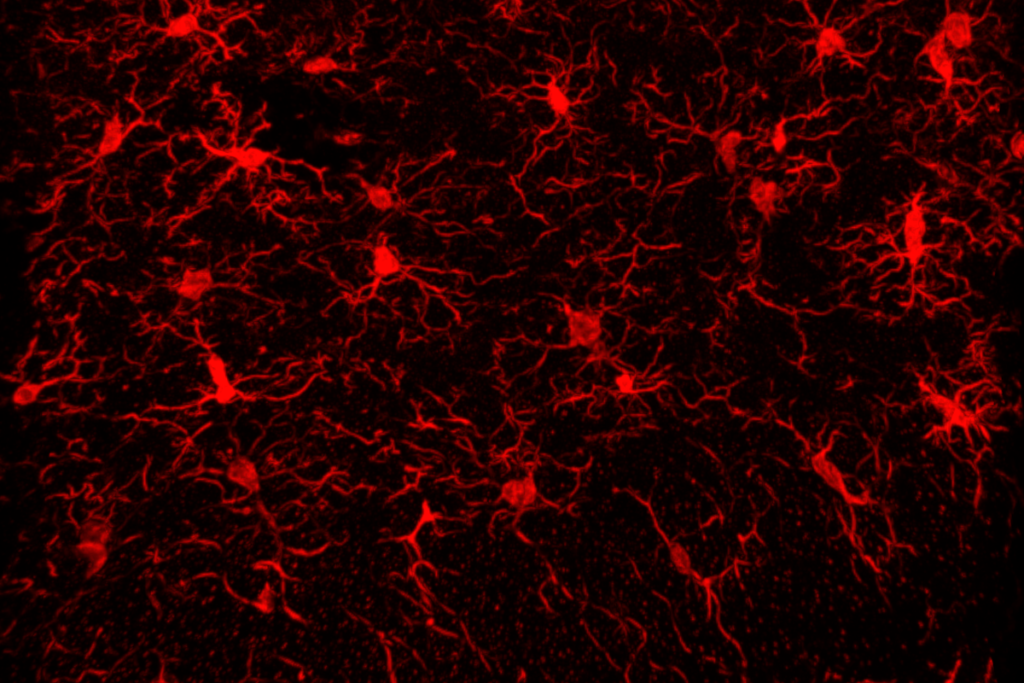

Microglia implicated in infantile amnesia

Explore more from The Transmitter

Probing the link between preterm birth and autism; and more

Structural brain changes in a mouse model of ATR-X syndrome; and more