Jobs, relationships elude adults with autism

Nearly half of adults with autism live with a family member and about one in five is unemployed.

Nearly half of adults with autism live with a family member and about one in five is unemployed, according to a new analysis1. Only 5 percent have ever been married.

The findings suggest that many middle-aged adults with autism have little independence.

The work echoes a study from last year that found that about half of adults with autism live with a family member. The unemployment rate in the new sample is only slightly lower than the 27 percent reported in that study.

Understanding the daily lives of adults with autism will help researchers identify the types of resources they need to succeed in various areas of life, says lead researcher Megan Farley, a senior psychologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Waisman Center.

The new work is “one of the first systematic” studies of housing and employment among people with autism in the United States, says Shaun Eack, professor of social work and psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh. “This paper is incredibly important. It says that these children [with autism] do grow up, and they face tremendous challenges.”

Home base:

The data derive from a mid-1980s survey of autism prevalence in Utah involving 489 people2. The researchers contacted the 305 people from that survey who either met criteria for autism as children or would meet current criteria based on their medical records. Of the 305, 162 people or their caregivers responded; 127 of these people have intellectual disability, and 128 are men.

The researchers were able to confirm diagnoses in 93 people, using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule. Caregivers answered questions about employment, relationships and social service use.

Only 38 people had full- or part-time jobs; others had a ‘supported’ job or were otherwise considered to have an ‘occupation’ because they volunteered, attended a day program or worked for minimal pay at a sheltered workshop. The remainder, 30 people (20 percent), were unemployed.

Surprisingly, landing a job does not track with intelligence: Of the 38 employed individuals, 10 have IQ scores below 70, and of the 24 unemployed participants for whom the researchers have IQ scores, 5 score in at least the average range.

The results also suggest that many adults with autism lack autonomy. For instance, 44 percent had a legal guardian. Only 9 percent lived in a home they had purchased themselves or in their own apartment; the same proportion lived in an institution. And 35 percent lived in a group home, supported apartment or other supervised living situation. The remaining 47 percent lived with family. The findings appeared 20 December 2017 in Autism Research.

In many cases, parents shoulder the bulk of the responsibility for their child.

“Parents are continuing to provide a huge amount of support,” Farley says. “Parents are aging, and there is not a clear way for them to develop plans for care for their adult sons or daughters when they’re not able to care for them anymore.”

Rocky romance:

Romantic relationships are relatively rare among adults with autism: 67 percent of the caregivers said their adult child had no interest in a romantic relationship. The majority also reported that their adult children had never been on a date. Some caregivers said their child’s relationship, when it existed, was immature or dysfunctional. About half of the participants spent little or no time with peers.

Adults with autism are not totally isolated, however. More than 60 percent of them are involved in organized social activities, such as a church or the Special Olympics.

Autism diagnostic criteria were stricter in the 1980s than they are now. As a result, the participants are likely to have relatively severe autism features. Still, the findings seem to align with the “everyday reality” of today’s adults with autism, Eack says.

Some researchers caution against using standard measures of job and relationship success for people on the spectrum.

“What these rating systems generally don’t do a good job at is understanding how good the fit is between the person’s situation and what that person’s ability level is and what their own goals are,” says Paul Shattuck, associate professor at the A.J. Drexel Autism Institute in Philadelphia. People with autism and their families should be allowed to set their own goals — and measure achievement based on those, he says.

References:

Recommended reading

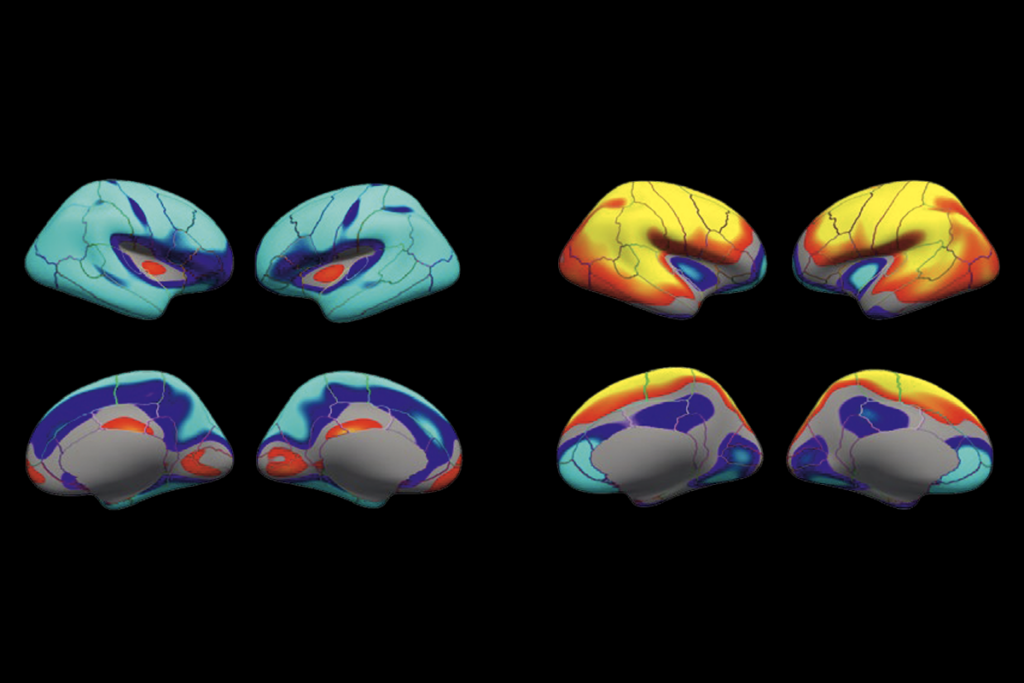

Poor image quality introduces systematic bias into large neuroimaging datasets

Probing the link between preterm birth and autism; and more

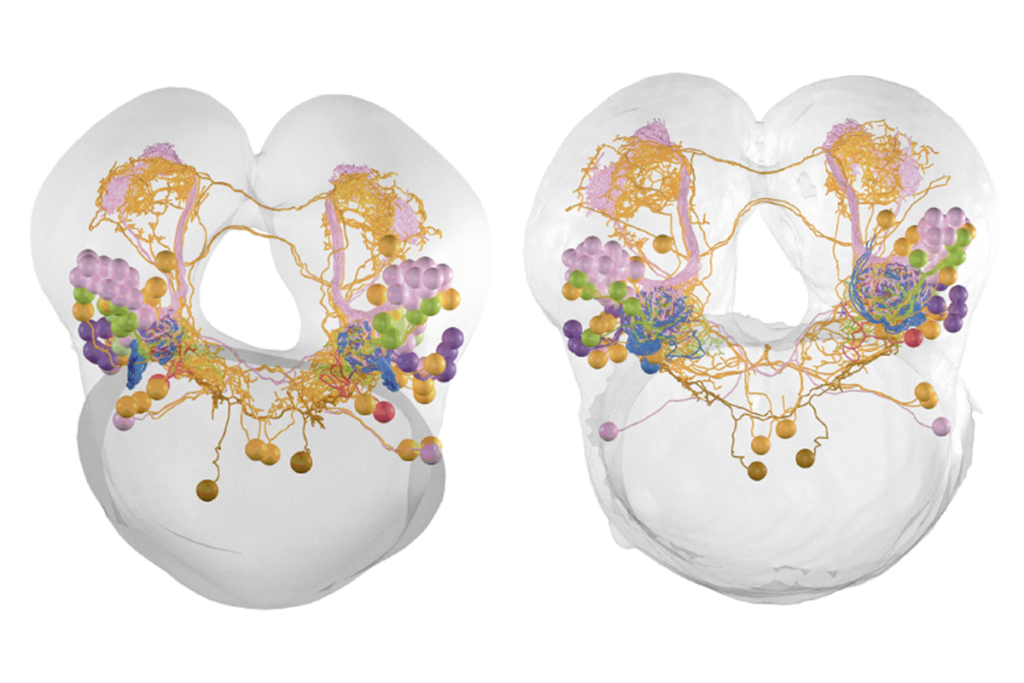

Cell ‘antennae’ link autism, congenital heart disease

Explore more from The Transmitter

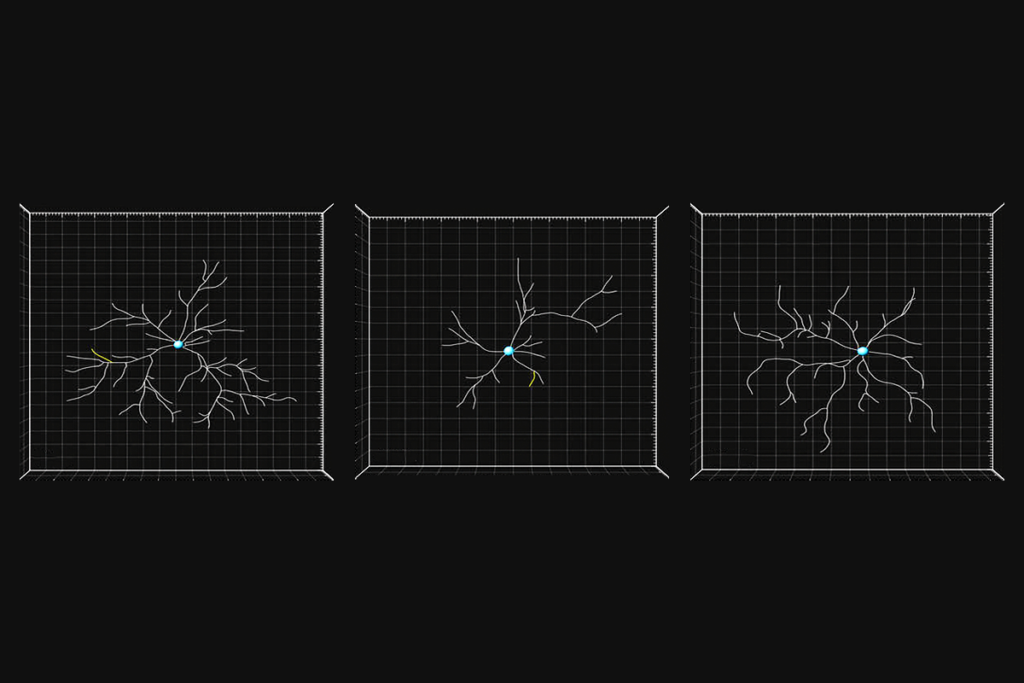

Cross-species connectome comparison shows uneven olfactory circuit evolution in flies

Null and Noteworthy: Downstream brain areas read visual cortex signals en masse in mice