Largest study to date confirms overlap between autism and gender diversity

People who do not identify with the sex they were assigned at birth are three to six times as likely to be autistic as cisgender people are.

People who do not identify with the sex they were assigned at birth are three to six times as likely to be autistic as cisgender people are, according to the largest study yet to examine the connection1. Gender-diverse people are also more likely to report autism traits and to suspect they have undiagnosed autism.

Researchers often use ‘gender diverse’ as an umbrella term to describe people whose gender identities — such as transgender, nonbinary or gender-queer — differ from the sex they were assigned at birth. Cisgender, or cis, refers to people whose gender identity and assigned sex match.

The results come from an analysis of five unrelated databases that all include information about autism, mental health and gender.

“All these findings across different datasets tend to tell a similar story,” says study investigator Varun Warrier, research associate at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom.

Autistic people are more likely than neurotypical people to be gender diverse, several studies show, and gender-diverse people are more likely to have autism than are cisgender people2,3.

But most previous studies have probed the relationship among people who sought gender-related medical care — often for gender dysphoria, a condition in which the ‘mismatch’ between gender identity and sex assigned at birth causes significant distress. That cohort doesn’t represent the full scope of gender-diverse people, says Aron Janssen, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois, who was not involved in the work.

“It’s so vital to understand this question outside of the clinical context,” Janssen says. “A more naturalistic study with this many participants outside of a clinical context really does provide a lot of support for this overlap.”

Gender and autism:

The five datasets together include 641,860 people, mostly adults; 30,892 have autism and 3,777 identify as gender diverse. The majority of the data — from about 514,000 people — came from an online survey conducted as part of a 2017 British television documentary about autism. (Simon Baron-Cohen, professor of developmental psychopathology at the University of Cambridge and the new study’s lead investigator, led the collection of those data.)

Three of the other datasets also used online questionnaires. The fifth came from a population study that collected information through primary care providers and included an optional online survey about autism traits. All of the studies included a question about autism diagnosis and asked for supplementary information, such as a participant’s age at diagnosis. One asked for a copy of medical records to confirm the diagnosis.

The surveys also gave different options for sex and gender: One included the terms ‘nonbinary’ and ‘other,’ for example, and another used variations on sentences such as “At birth I was registered as female, but I am male.”

About 30,000, or 5 percent, of the cisgender people in the study have autism, the researchers found, whereas 895, or 24 percent, of the gender-diverse people do.

Gender-diverse people also report, on average, more traits associated with autism, such as sensory difficulties, pattern-recognition skills and lower rates of empathy — or accurately understanding and responding to another person’s emotional state. And they are five times as likely to suspect they have undiagnosed autism as cis people are, based on one dataset of 1,803 people whose survey included this question.

The findings were published in Nature Communications in August.

The researchers also explored the relationship between gender identity and six mental health conditions, including schizophrenia, depression and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Many of these conditions co-occur with autism, and it has been unclear whether autism’s association with gender diversity is unique among these conditions, Warrier says.

Gender-diverse people have higher rates of all six conditions than cisgender people do, according to the new study. The association was highest for autism and depression.

Clinical implications:

The study reinforces trends seen in smaller studies, says Jeroen Dewinter, senior researcher at Tilburg University in the Netherlands, who was not involved in the research.

“They did a really great job in confirming earlier findings in a really careful way,” Dewinter says.

It also indicates a need for clinicians and educators to talk with autistic people about gender identity, Dewinter says, and to be aware of potential mental health impacts that can result from ‘minority stress’ — or the difficulties associated with being part of a marginalized group. Being both autistic and gender diverse can intensify such stress4.

“Clinicians and practitioners in both fields — autism and gender identity — need to be aware of this association, and to factor it into how best to support the person’s mental health,” Baron-Cohen says.

Nearly 70 percent of autistic gender-diverse adolescents say they need medical gender-related care, according to a small 2018 study, and 32 percent say their gender identity has been questioned because of their autism diagnosis5.

“It’s really, really distressing to read sometimes, where you have people who have very strong gender dysphoria and want to transition, and their therapist says, ‘Well, we need to first cure your autism before we transition,’ which is wrong on all levels,” Warrier says. “We want this study to really demonstrate that both of these things can co-occur, and just because these things co-occur does not mean that one should be denied.”

The findings also suggest that researchers should investigate how autism presents in gender-diverse people, Warrier adds. Researchers have often missed autism in cisgender girls because they tend to show different traits than cisgender boys do, and the same may be true for gender-diverse people.

Further research should move beyond quantifying the relationship between autism and gender, Janssen says, and focus instead on investigating the research priorities and clinical needs of autistic gender-diverse people, as well as underlying causes of the overlap.

References:

- Warrier V. et al. Nat. Commun. 11, 3959 (2020) PubMed

- Walsh R.J. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 4070-4078 (2018) PubMed

- Strang J.F. et al. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 57, 885-887 (2018) PubMed

- George R. and M.A. Stokes J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 2052-2063 (2018) PubMed

- Strang J.F. et al. J. Autism Dev Disord, 48, 4039-4055 (2018) PubMed

Recommended reading

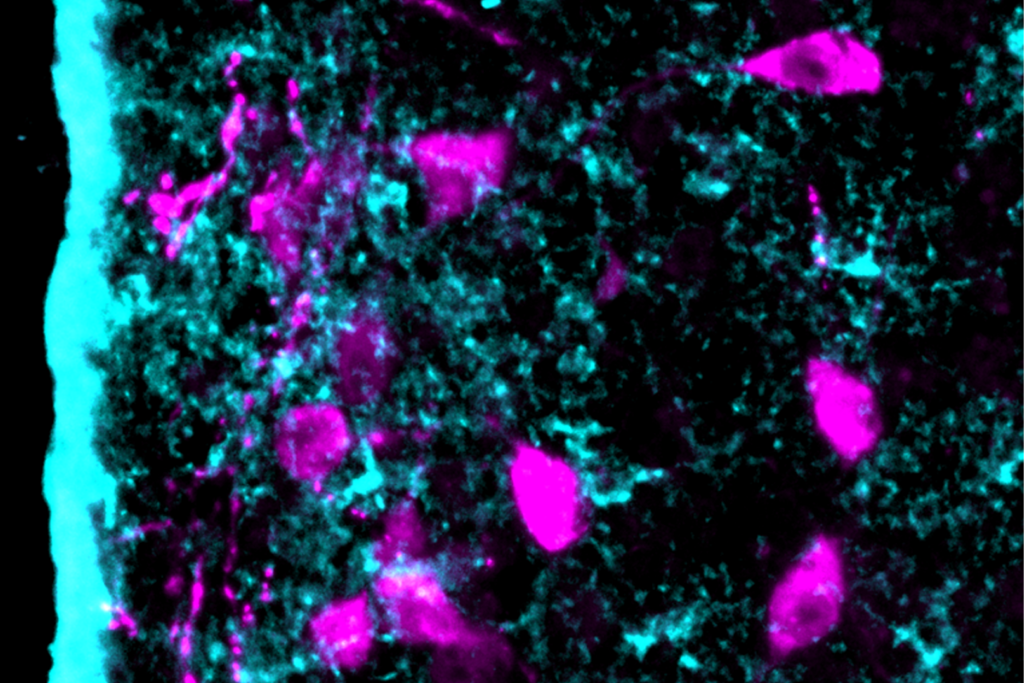

Astrocytes orchestrate oxytocin’s social effects in mice

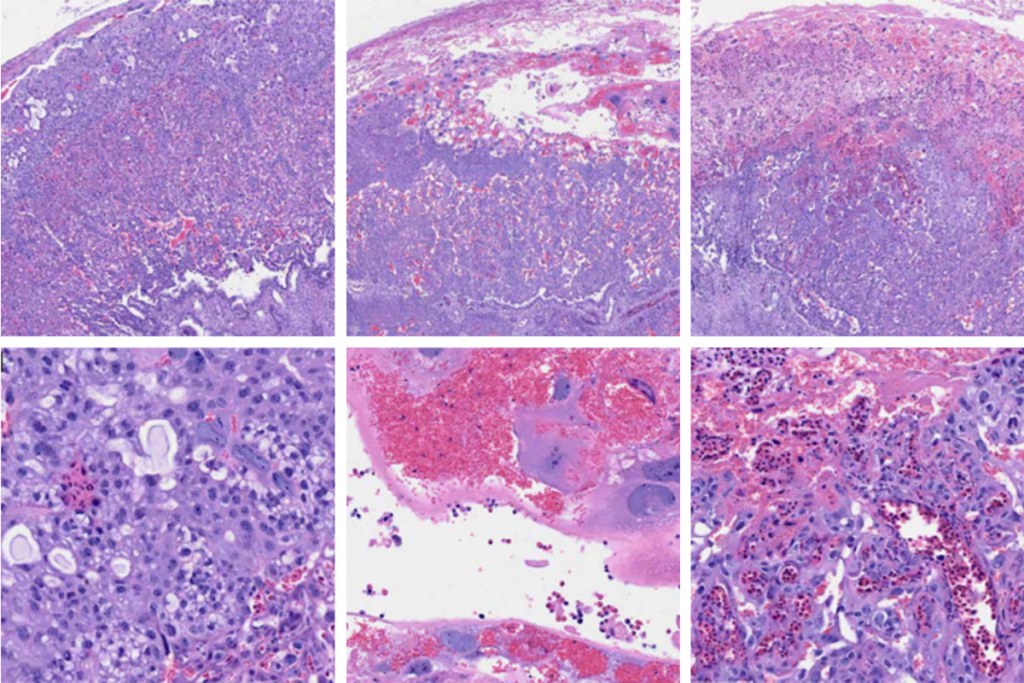

Post-infection immune conflict alters fetal development in some male mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Neuro’s ark: Spying on the secret sensory world of ticks

Lack of reviewers threatens robustness of neuroscience literature