A new method for delivering genes to the primate brain in utero enables researchers to adapt existing genetic tools to monkeys for the first time, according to a new study.

The approach could be particularly useful for studying development, says Cory Miller, professor of psychology at the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved in the work. “It’s super exciting.”

To genetically modify a nonhuman primate, scientists previously had three tools: Create a transgenic animal, which takes years to breed; inject a wildtype animal’s brain with a harmless adeno-associated virus carrying a gene, which remains localized to the injection site; or administer the virus intravenously, which requires large volumes to reach the brain, says study investigator David Leopold, chief of the Systems Neurodevelopment Laboratory at the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health.

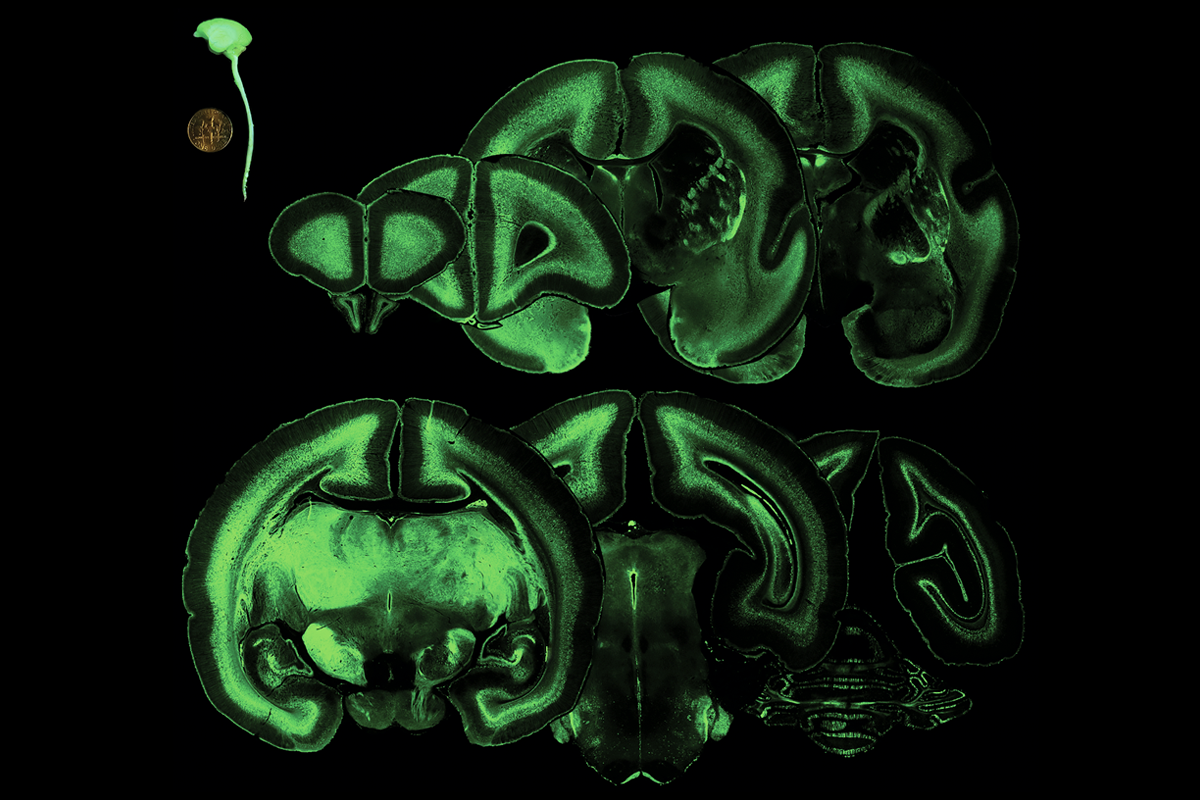

The new method adapts a protocol from mice that involves injecting a small amount of AAV into the brain’s cerebrospinal-fluid-filled ventricles. When given to newborn mice in this way, the virus transduces cells throughout the brain with long-lasting results. The approach is less effective in older mice, Leopold says.

The newborn primate brain is more fully developed than the newborn mouse brain. So to get high levels of virus throughout the brain, Leopold and his colleagues hypothesized that they might need to treat monkeys in utero and designed an ultrasound-guided system to do so.

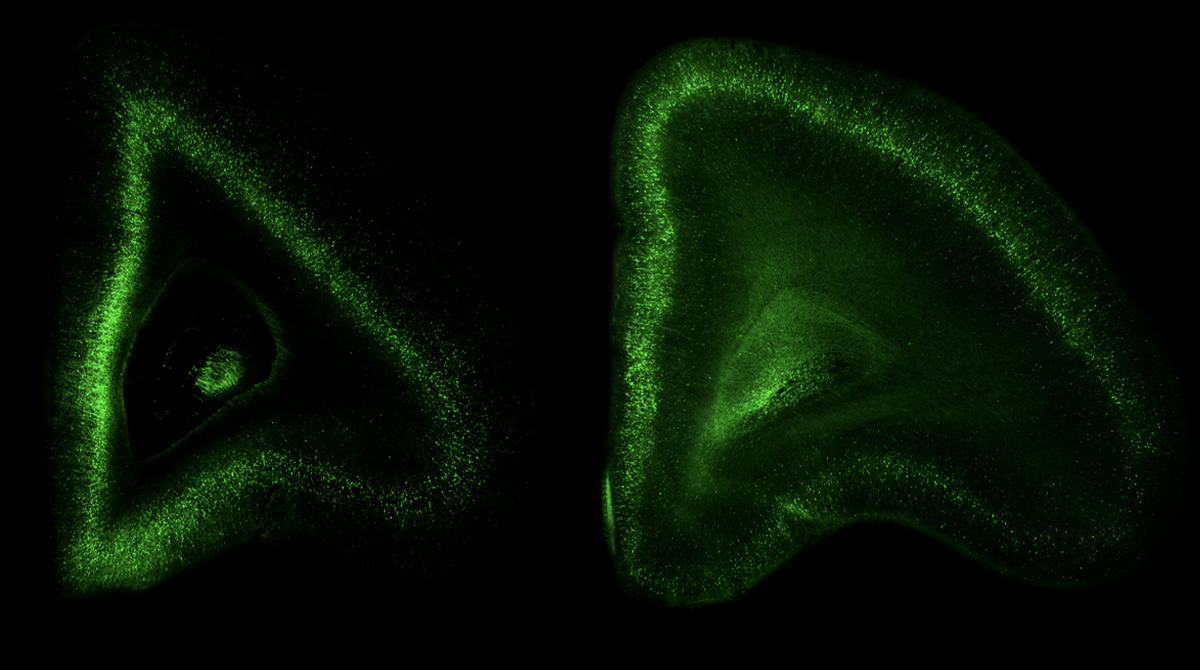

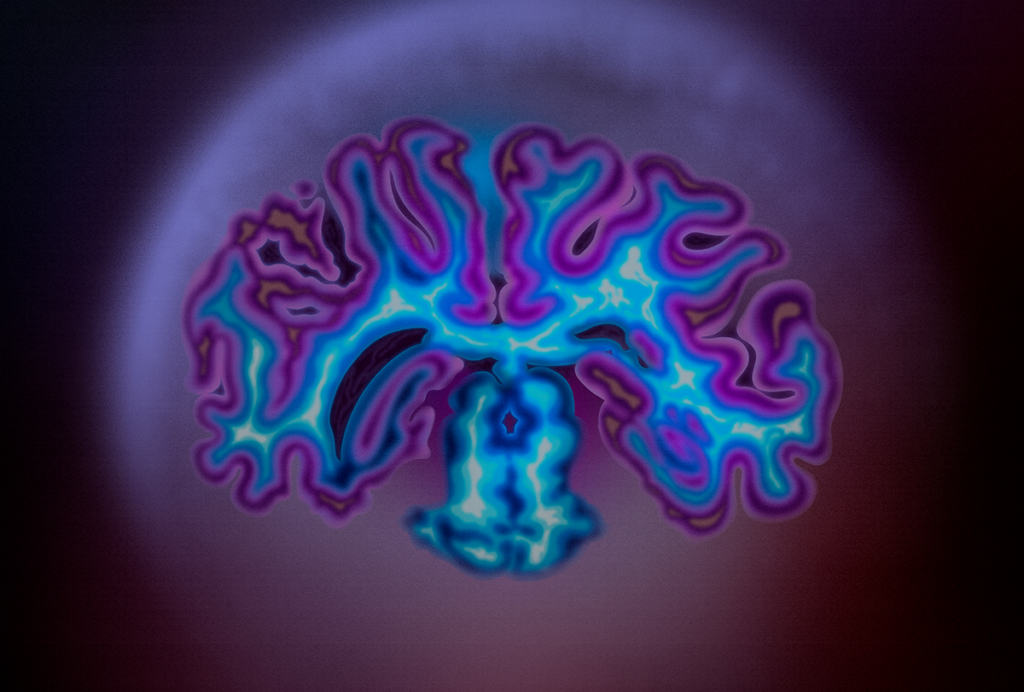

Doing so results in widespread viral expression throughout the animal’s brain that persists for more than two years after injection, the new work shows. The virus can be manipulated to express fluorescent tags or a CRISPR enzyme, and has potential for use with opsins to control cells with light.

“This work is about actually bringing all the genetic engineering technology into nonhuman primate models, and trying to do this as efficiently as possible,” says Afonso Silva, professor of translational neuroimaging and neurobiology at the University of Pittsburgh, who was not involved in the work.

D

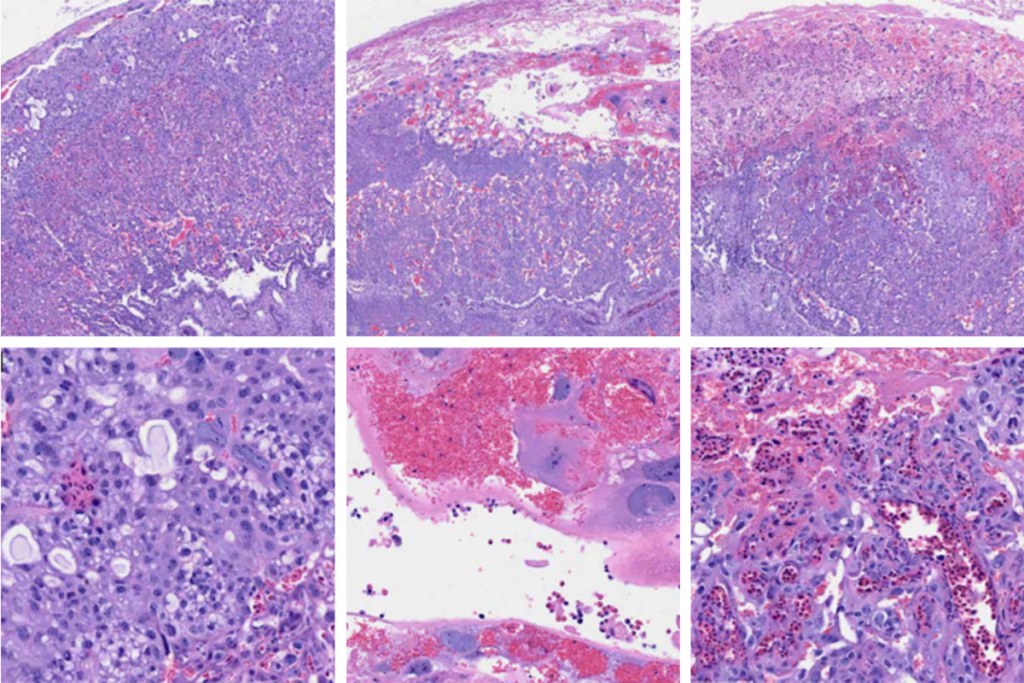

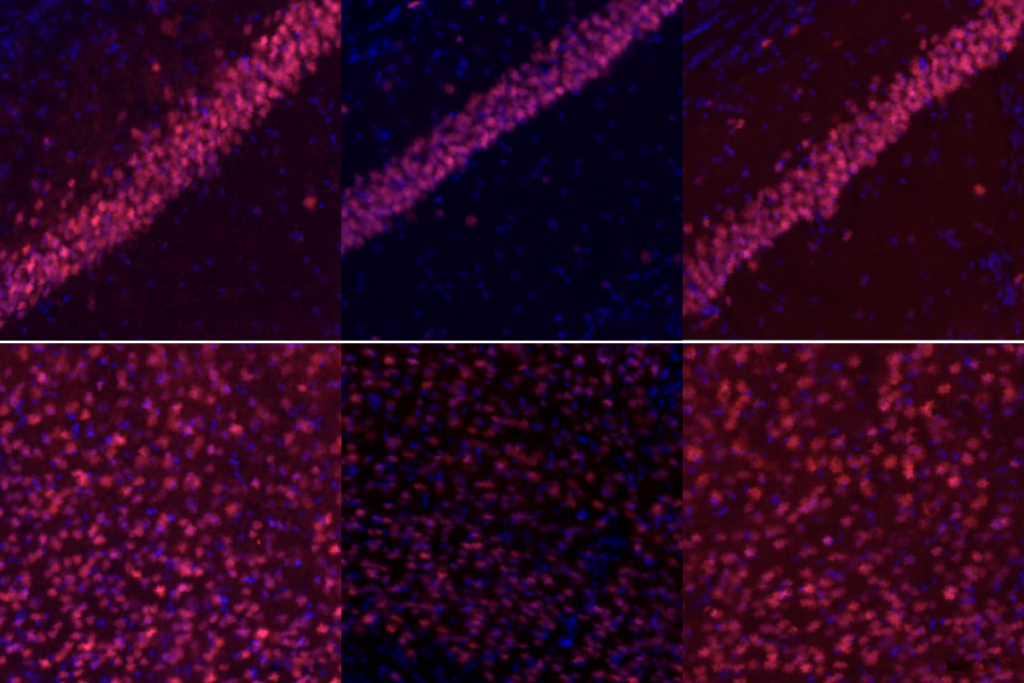

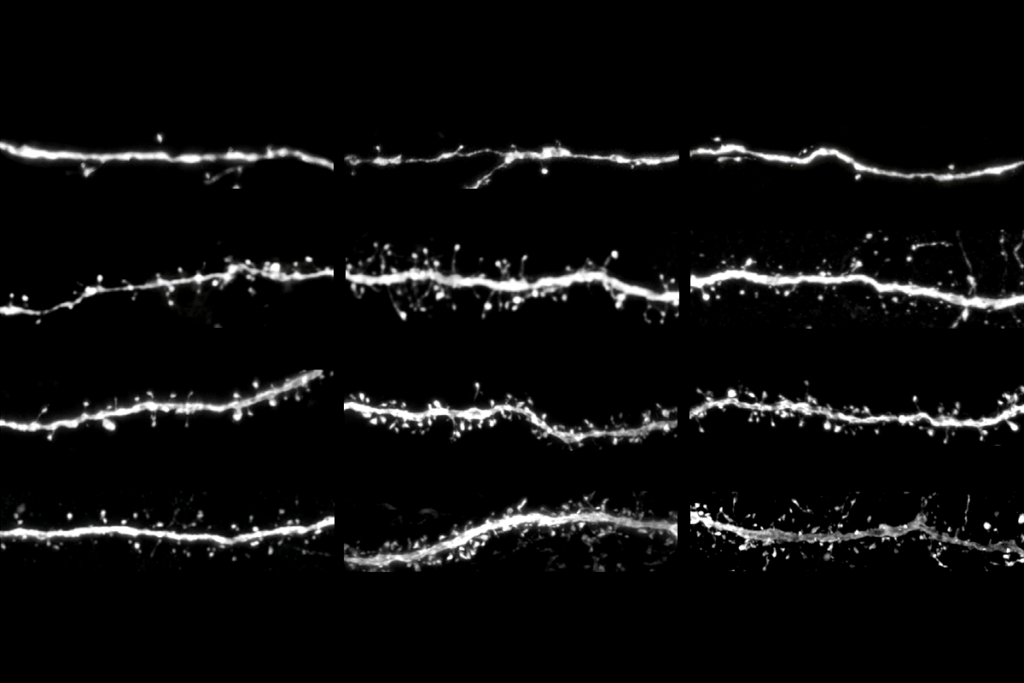

In another application for studying brain development, the researchers time-stamped the birth of a group of neurons by injecting a marmoset with two viruses. One virus produces the Cre enzyme in the presence of nestin, a protein temporarily expressed in newborn neurons. The other carries a red fluorescent reporter that activates when Cre is present. Neurons that appeared red in the animals’ brains had been expressing nestin, and therefore were recently born, at the time of injection.