Researchers unveil seven new rat models of autism

A large scientific research company debuted seven new rat models of autism Tuesday evening in Washington, D.C. Two of the models, one lacking FMR1 and the other lacking NLGN3, show some unexpected new characteristics.

-

Play partners: Rats have much more dramatic social behaviors than mice do, making them ideal for studying autism, researchers say.

Sigma Life Science, a St. Louis-based research company, debuted seven new rat models of autism Tuesday evening at the 2011 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Washington, D.C.

Six of the rats each lack one autism candidate gene — FMR1, NLGN3, MeCP2, NRXN1, CACNA1C and PTEN — and a seventh lacks mGluR5, which encodes a neuronal signaling receptor that is important in fragile X syndrome.

The impetus for making the rat models is to make autism research more attractive to the pharmaceutical industry. The standard approach in the industry is to test dosage and toxicology in rats, not in mice.

“Unless there’s investment, it doesn’t matter how many great ideas — which tend to be risky — you generate, they will not proceed forward,” says Robert Ring, vice president of translational research at the autism science and advocacy organization Autism Speaks. The idea is not to replace mice, Ring adds, but “to begin creating complementary animal models that help facilitate translational research.”

Over the past few months, Richard Paylor at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, has done behavioral testing on young rats missing FMR1 — mutations in which lead to fragile X syndrome— and NLGN3, one of the first genes implicated in non-syndromic autism.

Unexpectedly, some of the rat behaviors are the opposite of what’s seen in their mouse counterparts: The FMR1-deficient rats engage in social play less than controls do, for example, whereas some strains of mice lacking FMR1 have more social interactions than controls.

Rats missing either FMR1 or NLGN3 also show some unexpected new characteristics, such as severe female aggression and compulsive chewing on water bottles.

Big and bold:

For more than a century, the rat was scientists’ favorite laboratory animal. Then, in the mid-1980s, genetically engineered mice debuted, and rats slowly began to be relegated to the back bench. “Everybody moved to mice, whole facilities changed,” Paylor recalls.

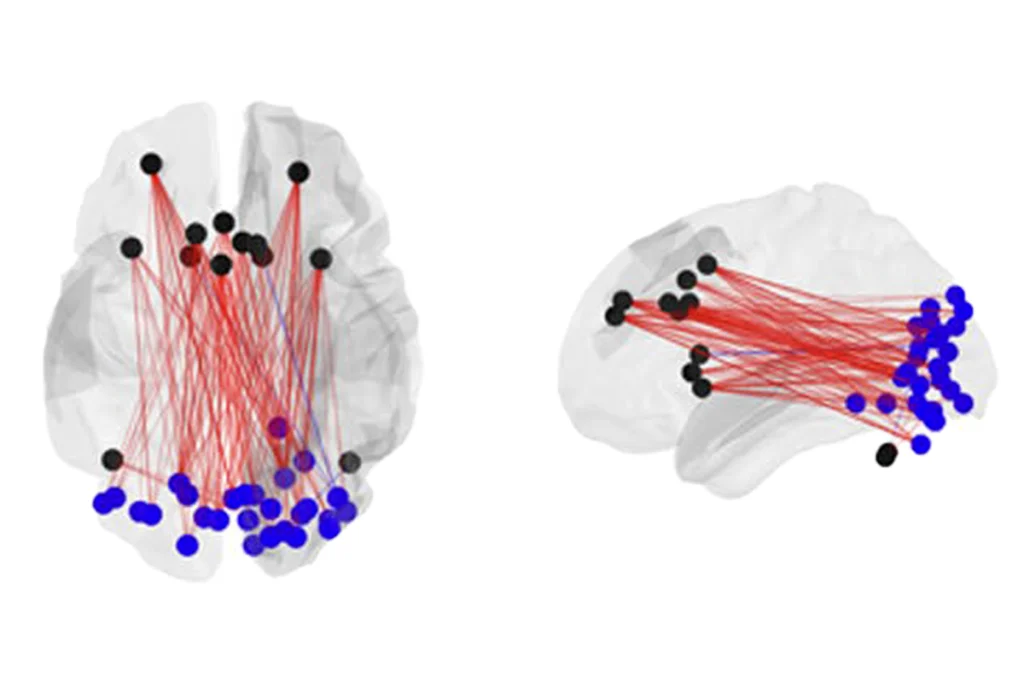

In many ways, though, rats are better suited for neuroscience. Their brains, and brain cells, are larger, making it easier to map out structures and connections.

“There’s so much more history on the anatomy of the rat,” says Caroline Blanchard, professor of genetics and molecular biology at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. “To replicate a literature that’s going back 100 years is no easy thing to do.”

Social behaviors are also tricky to measure in mice. “Their social play is not quite non-existent, but not much, really not much,” Blanchard says.

Rats, in contrast, live in large social groups and have dramatic interactions. When two rats meet for the first time, for instance, they immediately begin to rough and tumble. “We understand social play very beautifully in the rat, because it’s there. In the mouse, it’s very minimal,” says Robert Blanchard, Caroline’s husband and collaborator.

It’s much more difficult to manipulate a rat’s genetic make-up, however.

In 2009, Sigma Advanced Genetic Engineering Labs (SAGE) and a large team of researchers created the first rat lacking a targeted gene1. The company has since made a few dozen different rat mutants, including the seven new autism models.

Now that the technology has come of age, autism researchers may begin to look at rats anew.

“We worked on rats for many years,” says Jacqueline Crawley, an expert in mouse behavioral testing at the National Institute of Mental Health. “I don’t know, maybe we’ll all switch back.”

Scientists, especially those interested in measuring neuronal signaling, will definitely be eager to work with the rat models, says Matthew Anderson, associate professor of pathology at Harvard University.

“The one downside is the general cost,” Anderson says. The new rats cost $400 each, which is about ten times the price of a mouse. Rat housing is also much more expensive: A cage can hold five mice but only two or three rats.

Drama queens:

SAGE, a subsidiary of Sigma Life Science, created the rats using zinc finger nucleases, which recognize and cut particular DNA sequences. This effectively prevents the gene from making functional protein.

Through a joint project with Autism Speaks and SAGE, Paylor’s team is the only one with access to the autism rat models. Apart from the behavioral testing on young male FMR1 and NLGN3 models, his team is breeding rats lacking MeCP2, the gene mutated in Rett syndrome, and plans to begin work on the other four strains next year.

Paylor noticed differences between the rats and mice right away.

Rats are extremely sensitive to sounds and odors in the lab, for example. “They stop what they’re doing when they hear something,” Paylor says. “Everything about the rat is more dramatic.”

Female NLGN3 rats, which are used for breeding, are extremely aggressive. The researchers observed them frequently biting the feet and tails of male rats, and chewing on their cheeks. “We had to euthanize some of the males because the females beat them up — bad,” Paylor says. Sometimes, after an attack, the female cuddles underneath the male, “and he just takes it.”

Paylor also noticed something strange in the females’ cages: water bottles, made of hard plastic, with holes in them. The rats had chewed through them in two days. “We thought, no matter what this is, it’s a very perseverative behavior,” Paylor says.

To measure this more quantitatively in the male offspring of these females, Paylor designed a new ‘block chewing’ assay in which a small block of wood is placed in the rat’s cage overnight. After 16 hours, the researchers weigh the block to measure the chewing.

The FMR1 rats chew off more of the wood than controls do. The NLGN3 rats don’t chew the blocks — they chew through the water bottles instead.

Testing social behavior in these rats is more time-consuming because researchers must manually score the animals’ complex behaviors — including wrestling, boxing, chasing and grabbing one another’s necks. Two pairs of FMR1 rats analyzed so far are less social than controls, and emit fewer ultrasonic squeaks during play.

His team is assessing NLGN3 mice for social behaviors. Based on what the researchers have noticed in the cages, he says, he expects “to see some very dramatic differences in their social behaviors.”

For more reports from the 2011 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

References:

1: Geurts A.M. et al. Science 325, 433 (2009) Full Text

Recommended reading

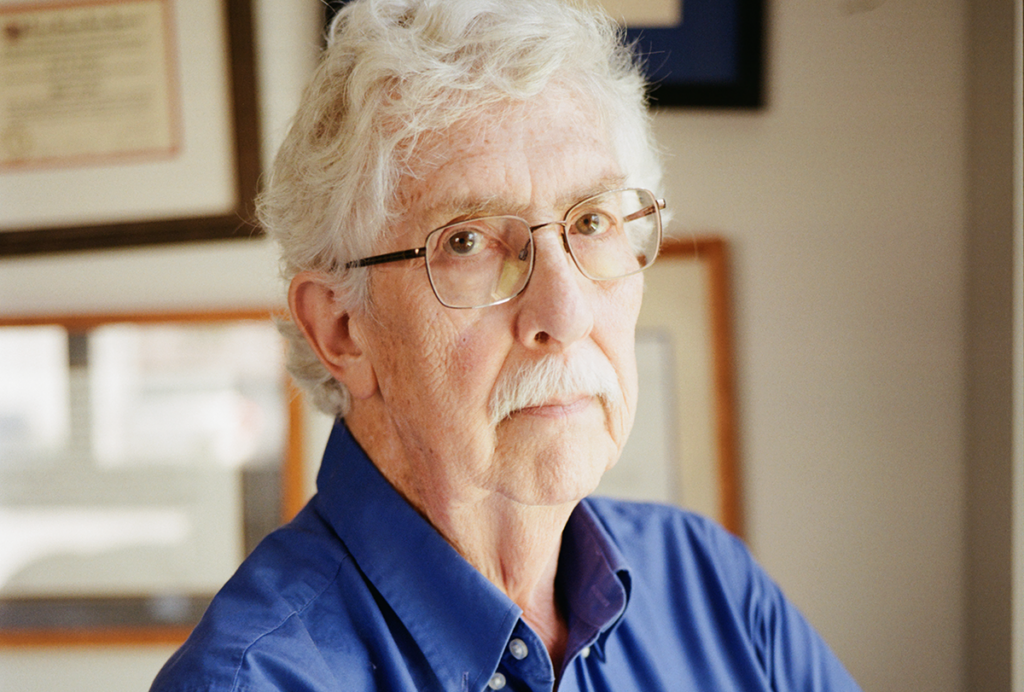

How pragmatism and passion drive Fred Volkmar—even after retirement

Altered translation in SYNGAP1-deficient mice; and more

CDC autism prevalence numbers warrant attention—but not in the way RFK Jr. proposes

Explore more from The Transmitter