Reward-system differences may underlie multiple autism features

The brain’s system for sensing pleasure and reward shows unusual activation patterns and an atypical structure in people with autism.

Listen to this story on iTunes, Spotify, iHeartRadio and Google Play, or with Alexa or Google Home. Ask for ‘Spectrum Autism Research’

The brain’s system for sensing pleasure and reward shows unusual activation patterns in people with autism, according to an analysis of 13 imaging studies1. A second new study points to an altered structure of reward circuits in autism2.

The results support the social motivation hypothesis, which holds that people with autism find social interaction less rewarding than other people do. A poorly functioning reward system may leave infants and young children unmotivated to engage with others. As a result, they may get few chances to practice and develop their social skills.

The problem is not limited to social motivation, however. The results of the meta-analysis show that the autism brain also responds uniquely to nonsocial rewards, such as winning money or a game.

“It provides compelling evidence of an expansion of the hypothesis,” says Rebecca Jones, assistant professor of neuroscience in psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, who was not involved in the work. “It’s not necessarily social only.”

In the meta-analysis, researchers used cutting-edge software that enabled them to combine raw data from multiple imaging studies.

This approach “allows you to more intelligently look around different parts of the brain that individual papers may have not focused on,” says lead investigator John Herrington, a psychologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “If you look across different studies, you actually can see more subtle patterns start to pop out.”

So far, the bulk of research on autism and social motivation is based on small studies.

“Not surprisingly, a lot of the findings from these smaller studies were not consistent, and the field really needed a meta-analysis to extract some consistent patterns.” says Gabriel Dichter, associate professor of psychiatry and psychology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dichter was not involved in the meta-analysis but wrote an accompanying editorial3.

The meta-analysis, which appeared in June in JAMA Psychiatry, is based on a fairly small number of studies, Dichter says.

Still, evidence for alterations in the reward system in people with autism is accumulating. The other new study reveals that autistic children have fewer nerve tracts between two parts of the reward circuit: the ventral tegmental area and the nucleus accumbens. These regions also show less synchrony in their activation when the children view pictures of faces versus pictures of landscapes. Those results were published 17 July in Brain.

Rewarding topics:

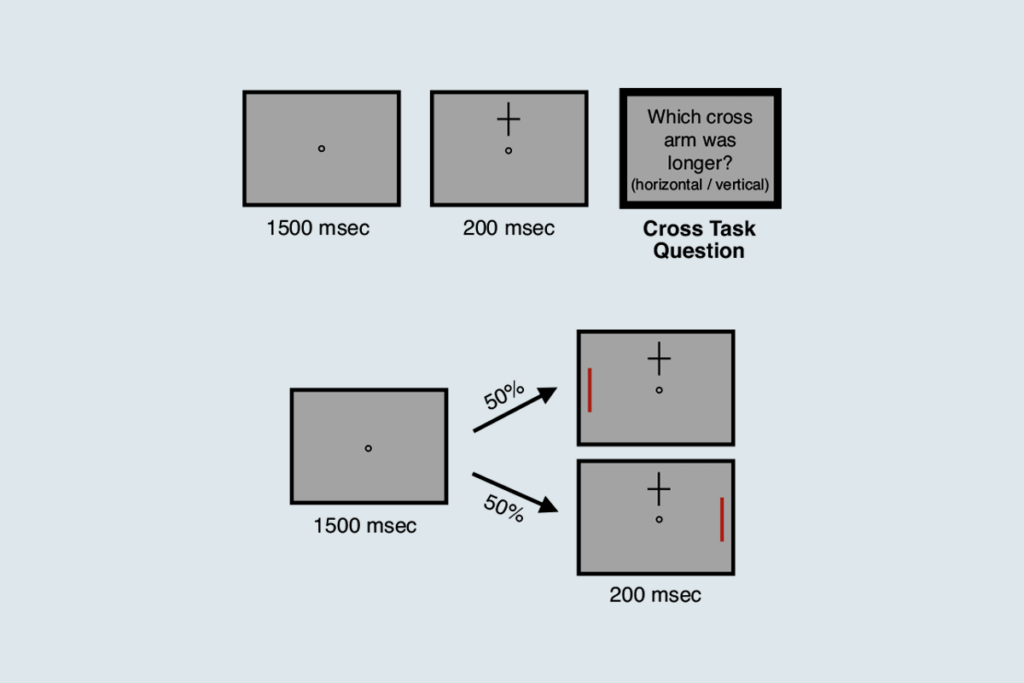

The studies in the meta-analysis included a total of 259 people with autism and 246 controls. Seven of the studies tested social stimuli such as seeing a person smile and wave, and 10 included tests of nonsocial rewards.

Overall, the analysis indicates weak activation of the system in people with autism in response to both social and nonsocial reward. The analysis suggests weak activation particularly in the caudate nucleus, nucleus accumbens and anterior cingulate gyrus.

The researchers also identified pockets of increased brain activation in autistic people. These regions include the right insula and putamen in response to social rewards, and the left insula and left caudate nucleus in response to nonsocial ones.

Three of the studies looked at how the reward system responds to images related to restricted interests, such as trains or computers. They suggest that the reward circuit goes into overdrive in people with autism in response to pictures of their interests.

For example, a study published in January revealed that, in children with autism, watching short movies related to a favorite activity or topic elicits much stronger reward responses than do videos of social scenarios4. In typical children, reward regions respond similarly to the two types of videos.

The study supports the idea that people with autism may have restricted interests and repetitive behaviors because they are disproportionately rewarding, says Benjamin Yerys, a child psychologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who led the imaging study and also worked on the meta-analysis. Over time, he says, these interests may crowd out more typically rewarding things such as social interaction.

References:

Recommended reading

INSAR takes ‘intentional break’ from annual summer webinar series

Dosage of X or Y chromosome relates to distinct outcomes; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Xiao-Jing Wang outlines the future of theoretical neuroscience

Memory study sparks debate over statistical methods