Spotted: Microbiome mania, CRISPR cousins

Researchers call for a massive collaboration to study the microbiome, and the gene-editing tool CRISPR is in good company with the discovery of three similar systems.

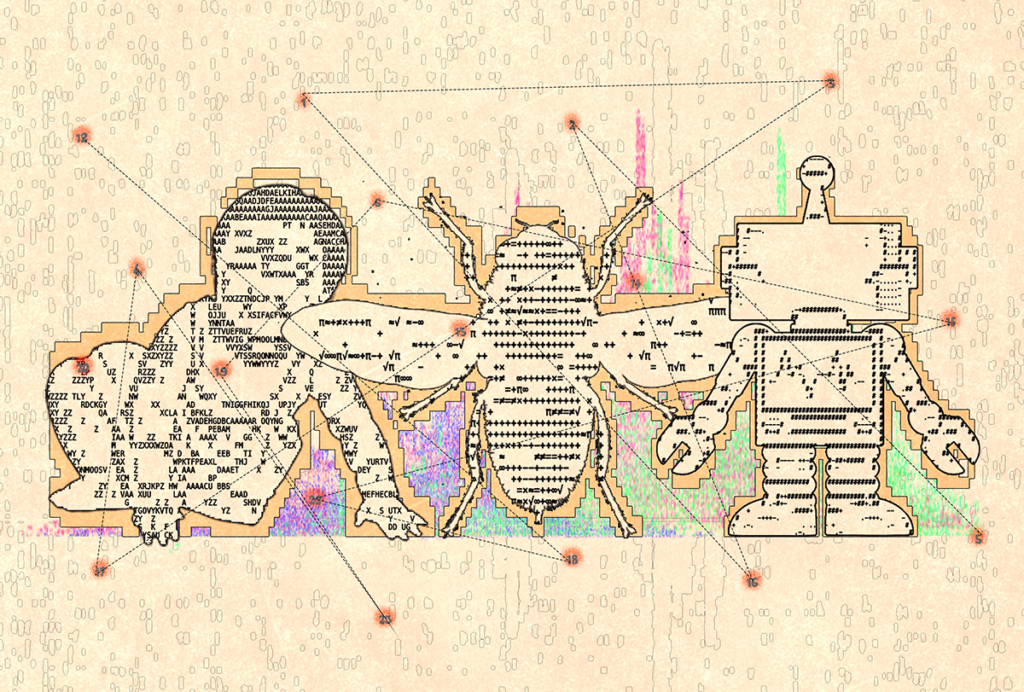

- Interest continues to bloom around the microbiome — the world of bacteria living in our soil and our bodies. This curiosity reached a peak on Wednesday when a group of microbiologists called for the creation of a Unified Microbiome Initiative (UMI).

The UMI would be akin to a bacterial version of the BRAIN Initiative, a national effort to understand the healthy brain and how it changes with disease. It’s estimated that there are 10 times as many bacterial cells in our bodies as there are human cells, but researchers know little about these bugs and what they do.

“We’re trying to put together an extraordinarily complex puzzle with just a fraction of the pieces,” Jeffrey Miller, professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics at the University of California, Los Angeles, told The Atlantic.

The effort could help autism researchers understand how microbes in our guts help to shape our brains.

- Researchers have uncovered three alternative versions of the gene-editing tool CRISPR. The discovery, published 22 October in Molecular Cell, could make it easier to delete, duplicate or mutate DNA in cells and animals.

Like the original CRISPR system, its newly discovered cousins work by homing in on a specific DNA sequence and cutting into it. But they have slightly different properties, which may make them better suited for certain editing jobs.

- Why grovel for grants when you can work at Google? An article published last week in Nature explores why an increasing number of ‘biomedical superstars’ are leaving successful labs and high-profile posts to join the tech giant’s life sciences team.

“They’re being continuously recruited away,” Euan Ashley, associate professor of medicine and genetics at Stanford University in California, told Nature. “We’re in competition with Google and other tech companies, and generally they can pay a lot more than Stanford can.”

But money isn’t the only lure. Google’s gaggle of tech wizards, innovators and now life scientists means that possibilities for progress abound.

“What I find compelling is the immersion of people with strong technology backgrounds — hardware and software engineers — sitting next to people like myself,” Jessica Mega, who left a successful cardiology career at Harvard Medical School for the Googleplex in March, told Nature. “The impact feels very, very large.”

- After steadily swelling for three decades, the number of postdoctoral fellows at academic institutions is starting to shrink, according to a study published earlier this month in the Journal of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology.

The findings may reflect shrinking budgets at the National Institutes of Health and other funding agencies, lead researcher Howard Garrison, deputy executive director for policy at the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology in Bethesda, Maryland, told Nature. “This probably means that there is less science being done,” he said.

The number of Ph.D. students continues to grow. This suggests young scientists are seeking alternatives to the classic postdoc track, such as industry postdocs that prepare them for biotech jobs.

Recommended reading

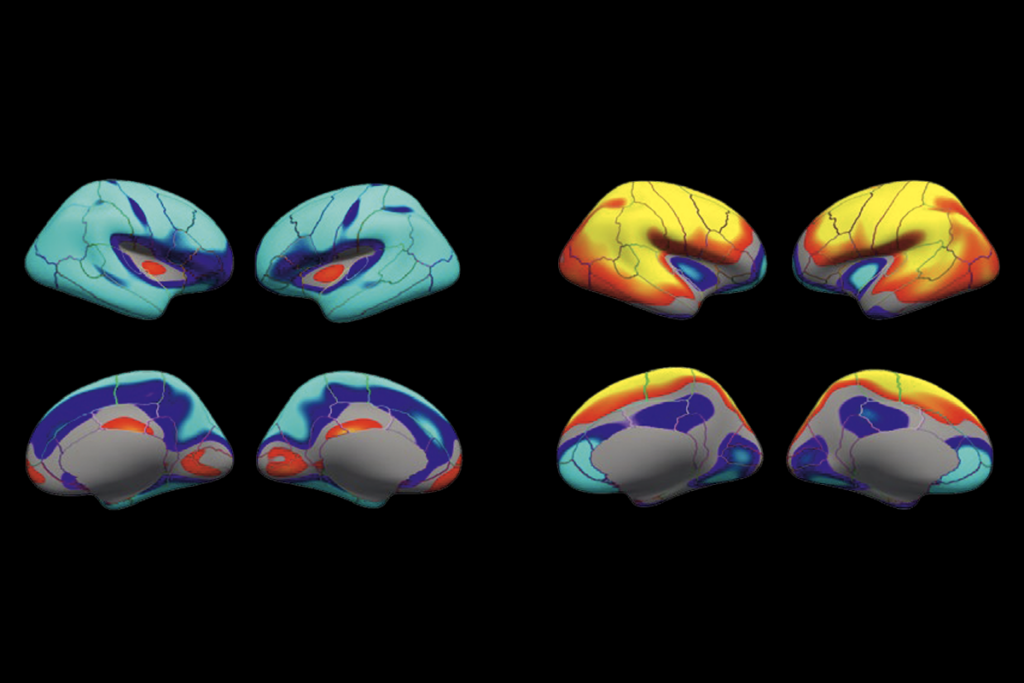

Poor image quality introduces systematic bias into large neuroimaging datasets

Probing the link between preterm birth and autism; and more

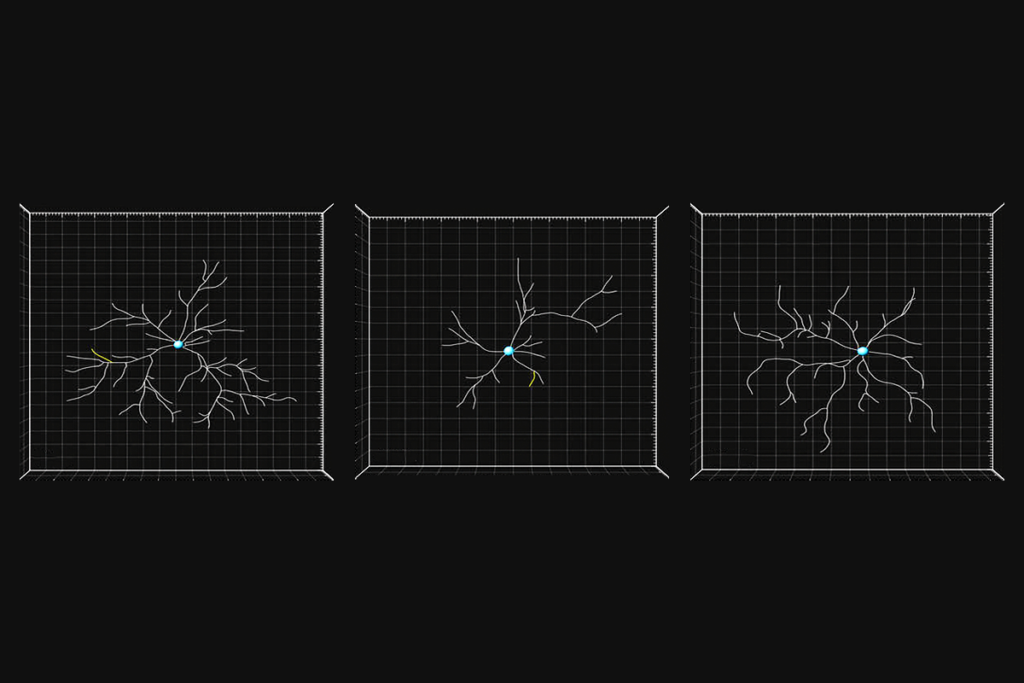

Cell ‘antennae’ link autism, congenital heart disease

Explore more from The Transmitter

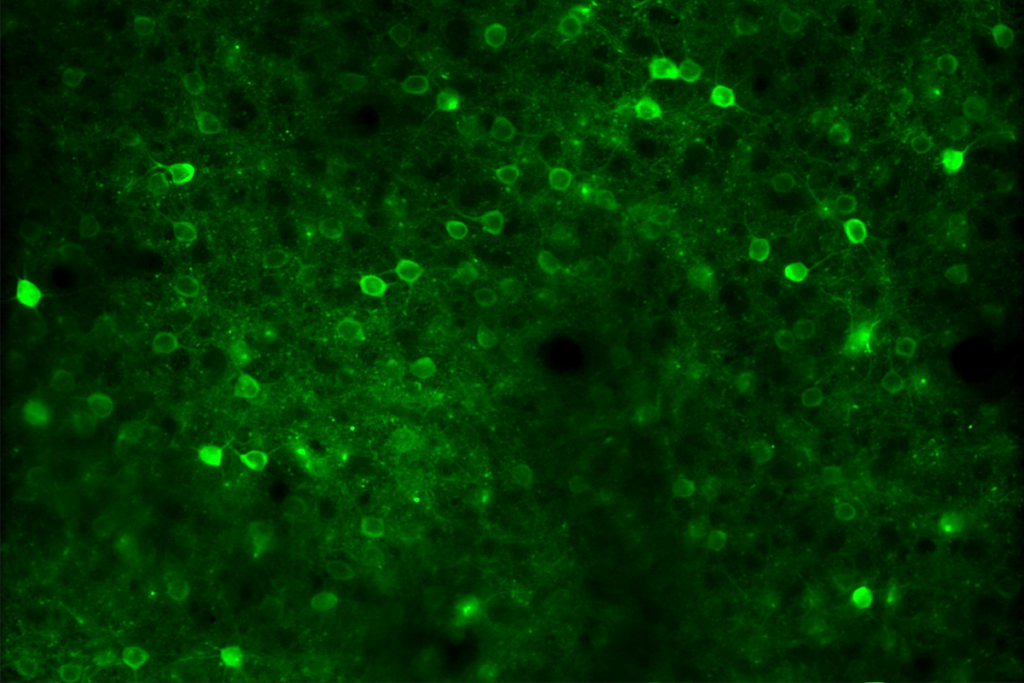

Null and Noteworthy: Downstream brain areas read visual cortex signals en masse in mice