A new type of progenitor cell found deep in the developing human brain spawns a steady supply of inhibitory interneurons and glia, according to a new study. The findings point to a potential origin of the inhibitory imbalance linked to autism and other conditions.

The study is a “tour de force” and “adds an important mechanistic piece” to understanding human interneuron diversity, says Xin Jin, associate professor of neuroscience at the Scripps Research Institute, who was not involved in the work.

Compared with other mammals, humans and other primates have larger populations—and a greater diversity—of inhibitory interneurons. It is not completely clear, however, where those extra neurons come from.

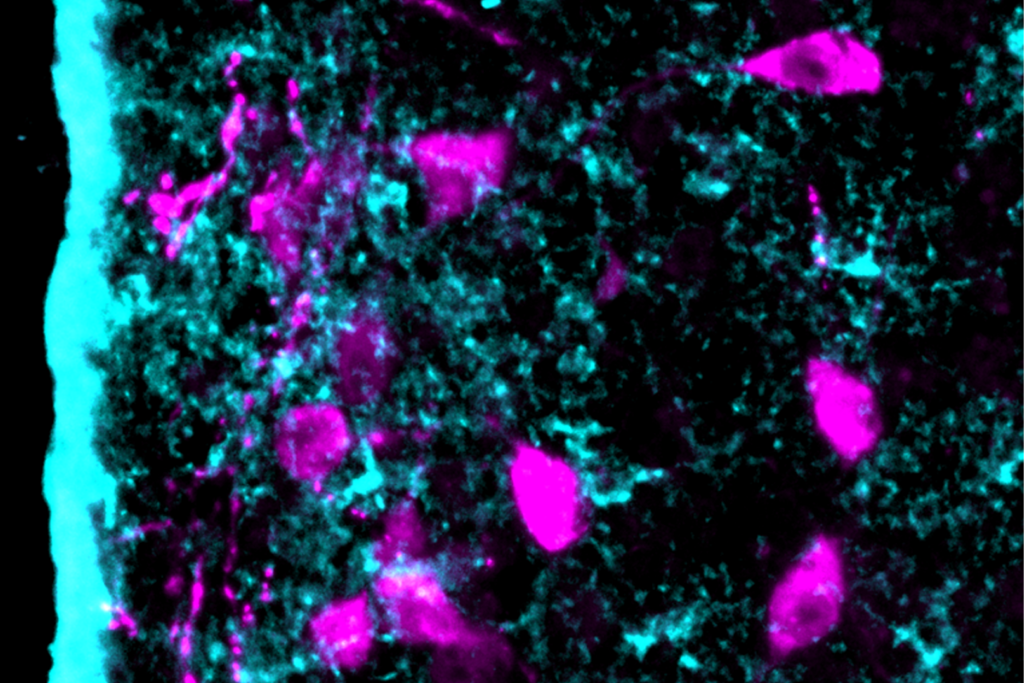

In mice, most interneurons are born in a brain structure called the medial ganglionic eminence and later migrate to the cortex. This structure, which forms transiently during fetal development, might be responsible for the expansion of interneurons during primate evolution, past research suggests. Humans and other primates have an enlarged region within the structure called the subventricular zone, where microglia gather to extend neurogenesis by secreting growth factors.

That region is also home to progenitor cells that continue to churn out GABAergic inhibitory interneurons into the final stages of pregnancy, the new study found. The cells appear to be “a main driving force for prolonged neurogenesis,” says study investigator Da Mi, associate professor of neuroscience at Tsinghua University.

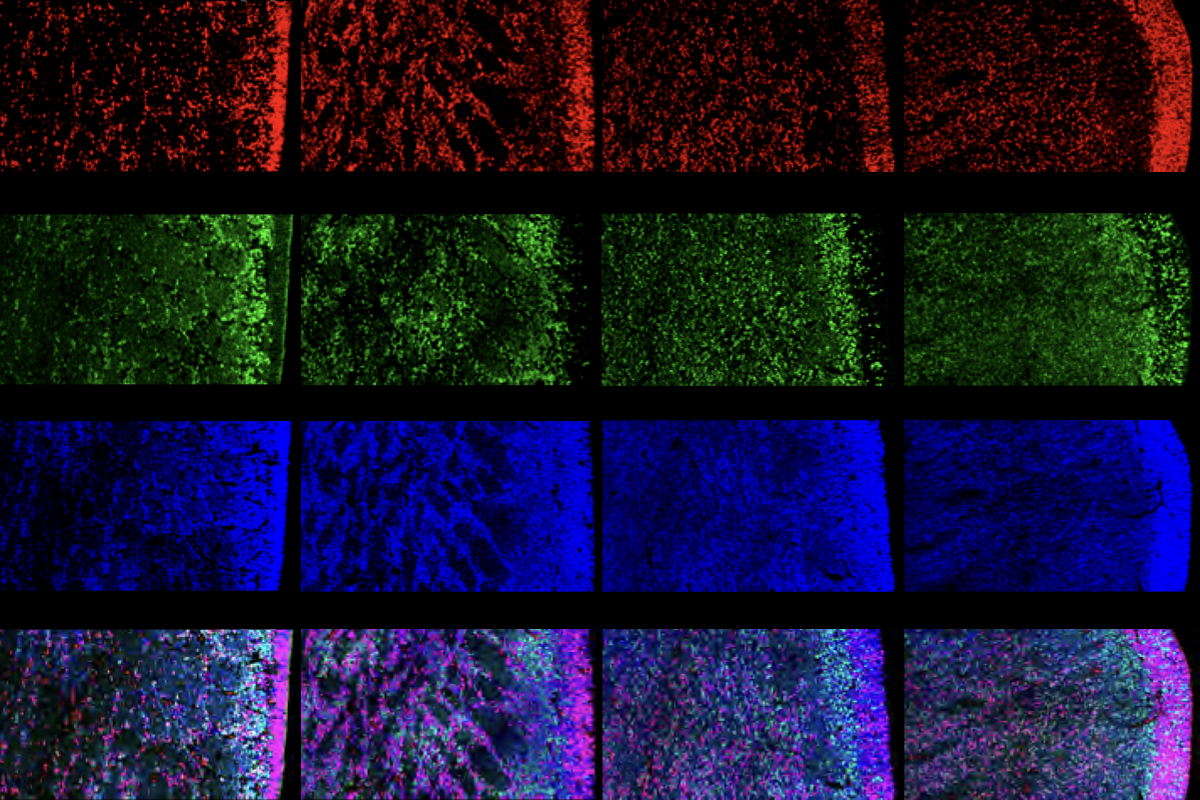

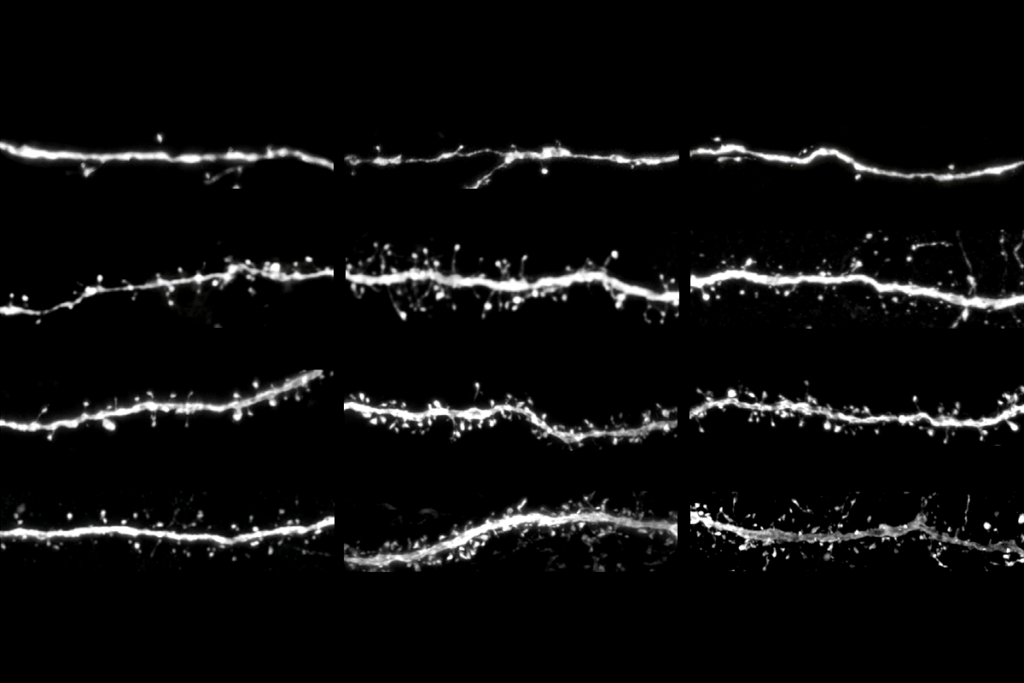

The progenitors—dubbed subventricular zone radial glial cells (SVZ RGCs)—surround nests of proliferative cells that are thought to contribute to human cortical development. Comparing brain tissue samples with those from other mammals, Mi’s team found a similar progenitor population in macaques but not mice, hinting that the cells may have emerged during primate evolution.

U

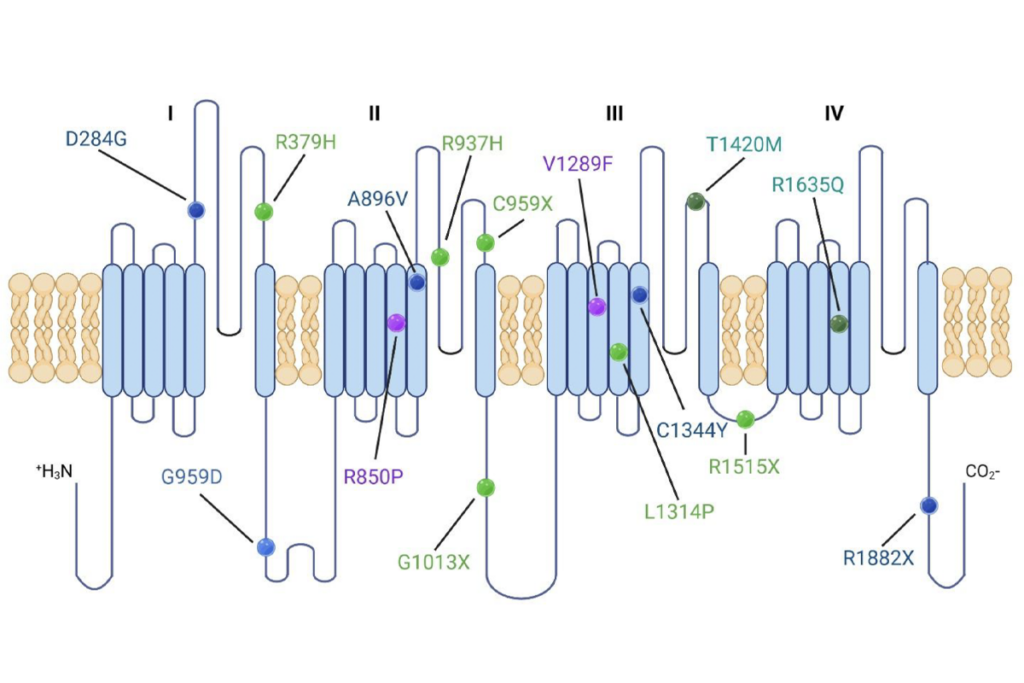

The findings, published 15 January in Science, challenge previous notions that neuronal progenitors are a homogeneous mass of cells, suggesting that SVZ RGCs activate transcriptional programs that drive cell fate before neurons integrate into circuits.

“That’s really impactful,” says Tomasz Nowakowski, associate professor of neurological surgery, anatomy and psychiatry, and of behavioral sciences, at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the new work. “It opens up a lot of questions but potentially provides some molecular handles that we can begin to mechanistically examine,” he adds.