The twenty-something free fall

Young adults with autism face many new expectations and challenges — with none of the support that is available during high school.

I

saac Law spends most of his time on his computer, watching movies on Netflix, poring through Facebook posts or working on his latest project, a web comic called “Aimless” about two friends named Ike and Lexis who leave Earth to join a band of space pirates.Law is 24, but he neither has a job nor attends classes. He briefly worked as a volunteer, stocking shelves in a comic book store, but that didn’t work out. “It was a very disorganized place,” he says. He also tried attending art classes. That didn’t pan out either. “I have massive authority problems,” he says.

In many ways, Law sounds like a stereotypical millennial — unwilling to work a dull job to pay the bills, and preferring to spend time on his creative interests. But Law’s path to an adult role and responsibilities is complicated by the fact that he has autism and bipolar disorder.

His mother, Kiely Law, is frustrated that he has, as she sees it, “plateaued” since graduating from high school at age 20. But as research director of the Interactive Autism Network, a registry for autism studies, she also knows that many young adults on the spectrum share her son’s difficulties transitioning to adult life.

“I think one of his challenges is that, like many adults with autism, he has some extremely narrow interests,” she says. “The opportunities that exist don’t fit what he’s interested in. And if you have difficulties relating to other people, and with social skills, and difficulties with transportation, it just snowballs.”

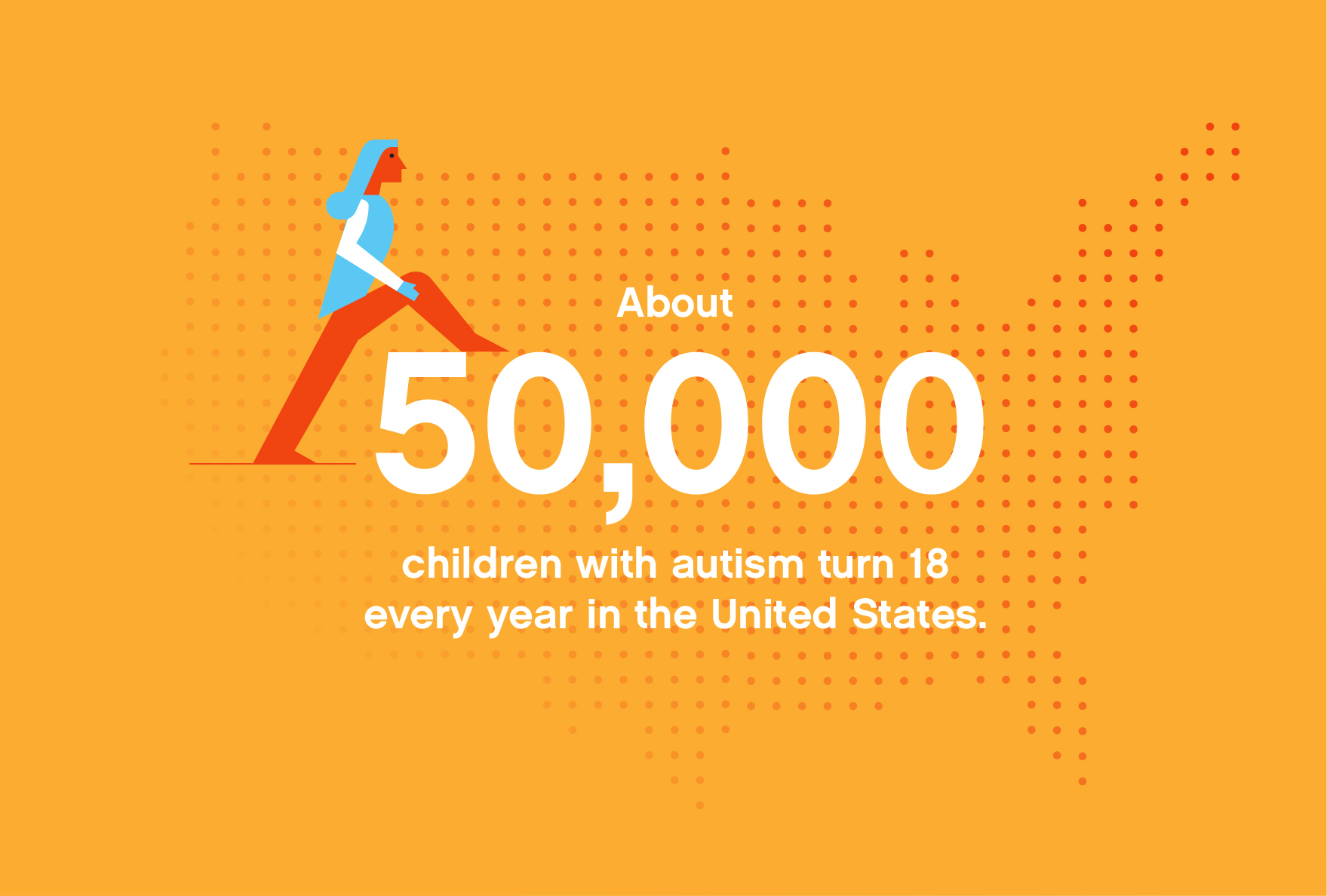

A giant wave of children diagnosed with autism in the 1990s are now reaching adulthood. Researchers estimate that about 50,000 young people with autism turn 18 every year. What’s clear is that this is a perilous phase for many of them, with at least three times the rate of social isolation and far higher rates of unemployment compared with people who have other disabilities. Whereas the majority of young people with language impairments or learning disabilities live independently, less than one-quarter of young adults with autism ever do so.

“There are a number of pretty good studies that describe fairly well the difficulties that young adults with autism face, in terms of unemployment and underemployment, in terms of comorbid mental health issues, in terms of not getting the services they need,” says Julie Lounds Taylor, assistant professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee.

So far, however, there’s been little research to determine what sort of support and services these young people need. Instead of getting extra help during these vulnerable years, they face a major impediment: a sudden drop-off in support at graduation, when federally mandated services abruptly end — a phenomenon that researchers call ‘the services cliff.’

It may be that with enough help, some young people on the spectrum would regain their footing as they continue to mature. Advocates and parents are pushing scientists to investigate practical questions that will improve the often grim outcomes for these young adults. Although the problems they face are well documented, the causes and potential solutions are unclear. Some autism researchers are collecting data they hope will illuminate just why so many young adults on the spectrum are struggling — and what they need to get through this transition. “We need to know what puts people on a path of upward mobility,” says Taylor.

Over the cliff:

T

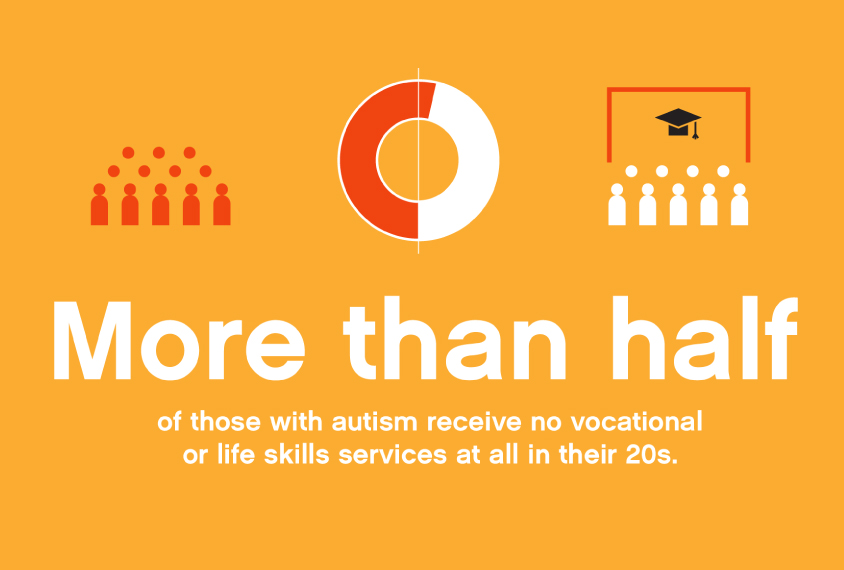

he period between ages 18 and 28 is critically important in establishing a foundation for adult life. For young people with autism, these years tend to be especially challenging. More than 66 percent of young adults on the spectrum do not secure a job or enroll in further education during the first two years after high school. Even two to four years later, nearly half are still not working or in school, according to the 2015 National Autism Indicators Report, produced by the A.J. Drexel Autism Institute in Philadelphia. And they struggle in other ways: One in four young adults on the spectrum is socially isolated, according to the report; only one in five has ever lived independently by their early 20s. Many also have two or more physical or mental health conditions in addition to autism, making it difficult to meet these milestones of adulthood.In fact, the limited number of studies on young adults who have autism show that many lose ground once they leave school. While teens with autism are in high school, their autism features generally tend to improve over time, but progress slows dramatically after graduation. In a 2010 study, researchers found that once adolescents leave school, any improvement they had shown in repetitive behaviors, reciprocal social interactions and communication basically stalls. Meanwhile, those who had shown progress in problem behaviors such as self-injury and aggression backslide. “We found that when they left high school, that improvement slowed down a ton and in some cases even stopped,” says Taylor, who led the study.

The likely reason, Taylor and other researchers say, is that support for adolescents vanishes after graduation.

During high school, 97 percent of young people on the spectrum get some type of publicly funded help, according to the Drexel report, which is based on U.S. government statistics. For example, at age 17, about 66 percent of individuals with autism receive speech and language services; after high school, that dwindles to 10 percent. Similarly, the proportion of those receiving occupational or life skills therapy diminishes from more than half to just under one-third.

For many years, these problems weren’t even on researchers’ radar. “For the longest time, people were thinking about children and how to intervene in childhood,” Taylor says. It wasn’t until about a decade ago that she and other researchers began working to fill the gap — and encountered daunting obstacles.

For example, Vanderbilt University has an extensive autism research program, so when Taylor began studying young adults in 2009, she thought it would be easy to connect to potential study participants through the network. “I didn’t expect at all that it would be difficult to find families,” she says. She found that, in fact, it was “incredibly difficult” and much harder than persuading young children or their families to participate.

That may be because the autism community tends to be more tightly knit among families with younger children. Once children are older, families may not be as eager to participate in research because they no longer anticipate the kind of ‘quick fix’ they may once have hoped for.

Funding agencies also tend not to be interested in supporting studies that might help to tease out why the years after high school are difficult and disorienting, researchers say. That’s especially true for studies on services to help young people with autism transition to adulthood.

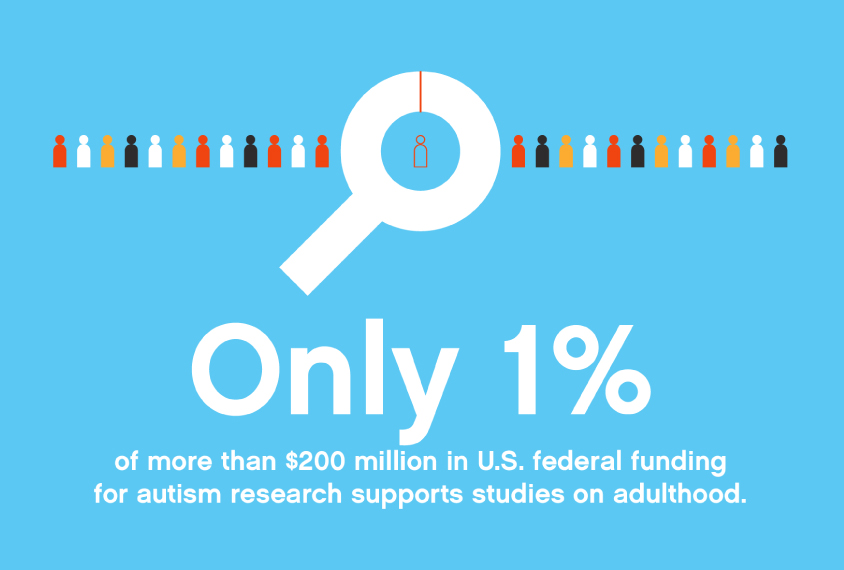

The overwhelming majority of autism research is focused on children. Between 2008 and 2012, only 1 percent of federal research funding for autism went to study issues of adulthood, according to a U.S. Government Accountability Office report. “The emphasis on brain and biology really pulls away from those kinds of studies,” says Catherine Lord, director of the Center for Autism and the Developing Brain at New York-Presbyterian Hospital in New York City. “It’s very hard to get funding for something that doesn’t have some kind of biological marker.”

Funding agencies also generally prefer research that explores ‘mechanisms’ underlying autism. That typically implies a biological approach, which further limits the scope of research, Lord says. “Most [scientists], when they are looking for mechanisms, are looking for things that can be easily translated into animal models.”

She proposes that scientists could interpret the idea of a mechanism more broadly, evaluating therapies that improve conversational skills or other aspects of daily living. Some evidence indicates that adults with strong adaptive living skills — such as communication and social skills, personal hygiene, cooking, cleaning and ability to use public transportation — are more likely to be employed and to be better integrated into their communities than those with poorer skills. But so far, not much research has explored adaptive functioning during the transition to adulthood for people on the spectrum.

Young adults have participated in numerous autism studies over the years — many imaging studies have scanned their brains, for example. But those studies, although interesting to researchers, typically don’t have much direct impact on the participants’ quality of life.

In some cases, the young adults themselves may be resistant. Isaac Law, for one, doesn’t believe that there is such a thing as ‘autism.’ “Most people labeled autistic are just plain oddballs,” he says. He rejects the diagnosis and has no interest in participating in studies — even though both his parents are autism researchers.

”“Health policy research has more to offer this group of individuals.” Kiely Law

Growing pains:

I

n 1990, Lord began tracking a large group of children with autism, starting at around 2 years of age. Her original intent was to determine whether it is possible to diagnose autism in children that early, and to explore whether the diagnosis remains stable into school age. About 130 people, now in their mid-20s, remain in the study. “About 45 people are verbal and really able to talk about what’s going on,” she says. The rest are intellectually impaired.Over the years, Lord and her colleagues have collected information on the participants’ behavior, adaptive living skills, educational achievements, daily activities, and their mental and physical health.

The team has found that the adaptive living skills of people who have both intellectual disability and autism continue to improve from age 18 to 26. “That’s one of the things that’s been encouraging for us,” she says. “They are still learning all kinds of things.” One reason for this is that people on the spectrum with intellectual disability have access to a wide range of services even after they leave school. “There are places for them to work when they come out of school, there are service systems in place to help them find things to do during the day, to find places to live if they don’t want to continue to live with their parents or they need help, and to get transportation.”

Paradoxically, the picture is bleaker for young adults with autism of average intelligence or above. Some who do well in high school seem to crash when they get to college, Lord says. And those who are not in college or working struggle to find ways to fill their suddenly empty days. These young people express more distress about their circumstances than do those who have intellectual disability. Their parents are more likely to rate them as anxious or depressed compared with parents of young people with both autism and intellectual disability.

“It’s much more difficult for the brighter, more verbal people with milder problems,” Lord says. Their own expectations — and those of their parents — are higher, for one thing. But they also face a more abrupt change in lifestyle, Lord says; they no longer enjoy the kind of structure and support that characterized their high school years. On their own for the first time in their lives, many flounder. And other than their parents, there’s no one around to help them navigate this sea of changes.

Few studies have probed just what sorts of help would actually improve quality of life for people on the spectrum. A 2012 review identified 23 studies focused on improving services for adults with autism; in 12 of those studies, the average age was 30 or younger. Most of those studies focused exclusively on employment, exploring job-skills training or support for people who already have jobs. Not a single study explored the range of services that people with autism might require, from medical and psychiatric services to transportation. States seldom pay for case managers to coordinate services, for people over 18 who don’t have intellectual disability.

Lord says that one big problem with young adult research is that it’s difficult to define what qualifies as a good outcome for a young person on the spectrum. A bright young woman with autism might find a job that doesn’t match her academic qualifications — but should that automatically be considered a poor outcome? What if she’s happy in the job?

“It makes us uncomfortable because it seems very arrogant for us to say, ‘This is a good outcome,’” Lord says. “That’s part of the complexity of this kind of research.”

These young people have their own priorities for the kind of research they believe should be funded, and those often differ vastly from what scientists or funding agencies would say. “For our independent adults, one of the top priorities is employment services: better support systems within the work environment,” says Kiely Law, who was involved in a 2015 survey of nearly 400 adults with autism and their caregivers in the Interactive Autism Network. The survey included people aged 18 to 71, with most in their 30s, but people of all ages agreed on this point.

Another priority was educational opportunities beyond high school, and the need for special support in that environment, Law says. An informal survey she carried out last year with a community advisory council turned up similar concerns. Apart from access to mental health providers, people on the spectrum report their research priorities to be work, education, bullying and discrimination, rather than biomedical research. But without evidence-based studies evaluating the cost and effectiveness of such programs, it’s unlikely that legislators will fund them.

Survey participants also mentioned the difficulty of finding healthcare providers — particularly specialists in mental health — skilled at working with adults on the spectrum. Once again, however, there is little information on how medication and other treatments for anxiety, depression and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder — all common among people on the spectrum — should be provided to adults with autism. “Health policy research has more to offer this group of individuals,” Law says.

Working it:

S

ara and Abby Alexis, 24-year-old twins, both have autism. Abby takes a class at the local community college and works one day a week in a hair salon where she folds clothes, sweeps hair and washes dishes. She has just started a second job at a café. Sara just completed a continuing-education art class and has two part-time jobs: folding towels at a fitness center and packaging soap at a personal care products company. They are two of the lucky few to have found jobs that work for them — thanks to a program launched by parents who solved the service-cliff problem on their own.The sisters got their jobs through Itineris, a community-based program created in 2009 by nine Baltimore families who realized that after high school graduation, there would be no specialized services available to help their children on the spectrum become more independent. In addition to providing job training, Itineris staff take the 70 or so young people in the program on outings to restaurants, amusement parks, movies and bowling.

Abby and Sara both love Itineris. “It’s good to make friends and be social,” says Sara. Abby has a boyfriend, whom she met at Itineris, and many friends. She is hoping to move into an apartment with her older sister in a year or two and become even more independent. “I want people to treat me like an adult, not like a kid,” she says. Working a paying job where she makes $9 an hour is part of that.

Researchers tend to focus on employment among young adults with autism for one simple reason. “We find that for many people, employment is not just about a paycheck. It’s about opportunities for social inclusion, meeting other people, for self-expression and identity formation,” says Paul Shattuck, director of the Life Course Outcomes Research Program at the A.J. Drexel Autism Institute.

But without the help of an organization like Itineris, finding a job is tough — and sticking with a job even tougher. Though about half of young adults on the spectrum work for pay at some point after high school, only one in five works full time, with average earnings of around $8 per hour. Their rates of employment are lower than those of people with language impairments, learning disability or intellectual disability alone.

Young adults with autism are more likely to work for pay if, like Abby and Sara, they are from middle- to high-income households and have decent conversational abilities and functional skills. Finding a job or being enrolled in school is no guarantee of consistent employment or earning a college degree, however. A 2015 study of 73 young adults showed that 49 either worked or were enrolled in some form of post-secondary education, typically college classes, at some point over the 12 years following high school graduation. However, only 18 were consistently employed or in school during that time. And only 3 of the 31 people who graduated from college found jobs in their field of study; most were either unemployed or had unskilled jobs in food service, retail or maintenance.

For young people from working-class and poor families, joblessness isn’t really an option, adds Shattuck. Last year, he and his colleagues launched a partnership with Philadelphia public schools and a state social services office to provide full-time internships and job training for young people with autism. The program is designed for people with intellectual disability; one participant is nonverbal, he says. Still, their families expect them to secure paying work of some kind. Most of the participants are African-American and come from families of modest means, Shattuck says. Families must apply to the program. “More importantly, each youth has to express a clear willingness and interest in working and learning,” he says.

The participants — only eight so far — rotate through internships in the Drexel University campus bookstore and other offices, with the aim of learning skills they can transfer to future jobs. “These are not volunteer ‘make-work’ positions,” Shattuck says. Though it is too soon to assess whether the program can help participants stay in jobs, Shattuck says that employers are pleased so far. “We’ve had tremendous buy-in from Drexel staff and supervisors.”

The researchers hope to expand the program next year. Funding comes from state and city agencies that already provide support for adults with intellectual disabilities, meaning that “it’s budget-neutral for those agencies,” Shattuck says. That should make it easier to replicate the program in other cities and states.

The limited research on young adults with autism makes it challenging to advocate for more services for them, says Shattuck. Legislators and their staffers all ask the same question: What proportion of young people on the spectrum will be able to live independently, and what proportion will need significant care for the rest of their lives?

“We don’t have the successful framework, the infrastructure, the tools to even answer those basic questions,” he says.

”“We need to know what puts people on a path of upward mobility.” Julie Lounds Taylor

New beginnings:

O

ne day when Renee Gordon’s son Alex was 21, he bolted out of a moving car in the middle of the freeway. In order to subdue him, the police eventually threw him to the ground and handcuffed him. The incident was the culmination of a bad period for Alex, who has autism and is intellectually disabled and nonverbal. His anxiety had become particularly intense following a series of significant changes, including the departure of a longtime caregiver and the loss of school friends. After the incident, his parents, approaching retirement age, decided that they could no longer provide the structured environment that Alex needed at home. They were worried that he would have difficulty adjusting, but his experience has revealed that for people with autism, change and growth can stretch far beyond the teen years.Alex moved to a group home in June 2014, where he now lives with two other men with disabilities and their caregiver. Gordon is astonished by the changes in her son. “It has been the most amazing transition for him,” she says. “He is far more independent, far more flexible.”

Alex still requires 24-hour care. But he has learned to zip his coat and pants, is far less fussy about food, volunteers at Meals on Wheels and attends social functions with his housemates and other peers, including a trip to the beach and a monthly nightclub at the League for People With Disabilities. And he finally has friends.

“We think that just because school ends at 18 or 21, that’s the end of learning,” Gordon says. But seeing the changes in her son, and recalling stories she has heard from other parents over the years about the great strides their adult children made in their 20s, she wonders if young adulthood might be the perfect time to teach new skills.

Shattuck says that he too has heard many “second wind” stories from parents about young adults with autism in their 20s and 30s. It leads him to ponder two fundamental questions: What are the conditions that facilitate this unexpected progress — and what’s going on in brain development that allows it to happen?

Shattuck doesn’t consider basic research and studies of services to be at odds. Understanding how the maturation and aging processes plays out in people with autism throughout life, he says, will improve their health, well-being and quality of life, as well as contribute to understanding mechanisms at the biological level. “It doesn’t have to be one or the other,” he says. “The point I try to make when talking to fellow scientists is: Yes, there is clearly a discrepancy between what the community wishes was funded and what actually gets funded. But I think it is a mistake to conclude that there needs to be a difference between those two goals.”

Gordon, who is married to a neurologist, agrees. Biological studies are important; so is research focused on what kind of help young adults like her son need right now, she says. “I would like more research into how you can make sure that these individuals have happy and fulfilling lives.”

For Isaac Law, happiness and fulfillment are represented by his web comic, which he hopes to publish by August 2018, when the Museum of Science Fiction opens in Washington, D.C. His dream is to be paid for his art as a cartoonist. “I would rather not get a job again,” he says. “I would just like to focus on my web comic if possible.”

The comic is a buddy comedy, centered around two friends who are inseparable. Law says he doesn’t have such a friend himself. The character of Lexis is based on his cousin, but, he admits, “we don’t talk to each other as often as we probably should.”

Syndication

This article was republished in Slate.

Recommended reading

INSAR takes ‘intentional break’ from annual summer webinar series

Dosage of X or Y chromosome relates to distinct outcomes; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Machine learning spots neural progenitors in adult human brains

Xiao-Jing Wang outlines the future of theoretical neuroscience