When autistic people commit sexual crimes

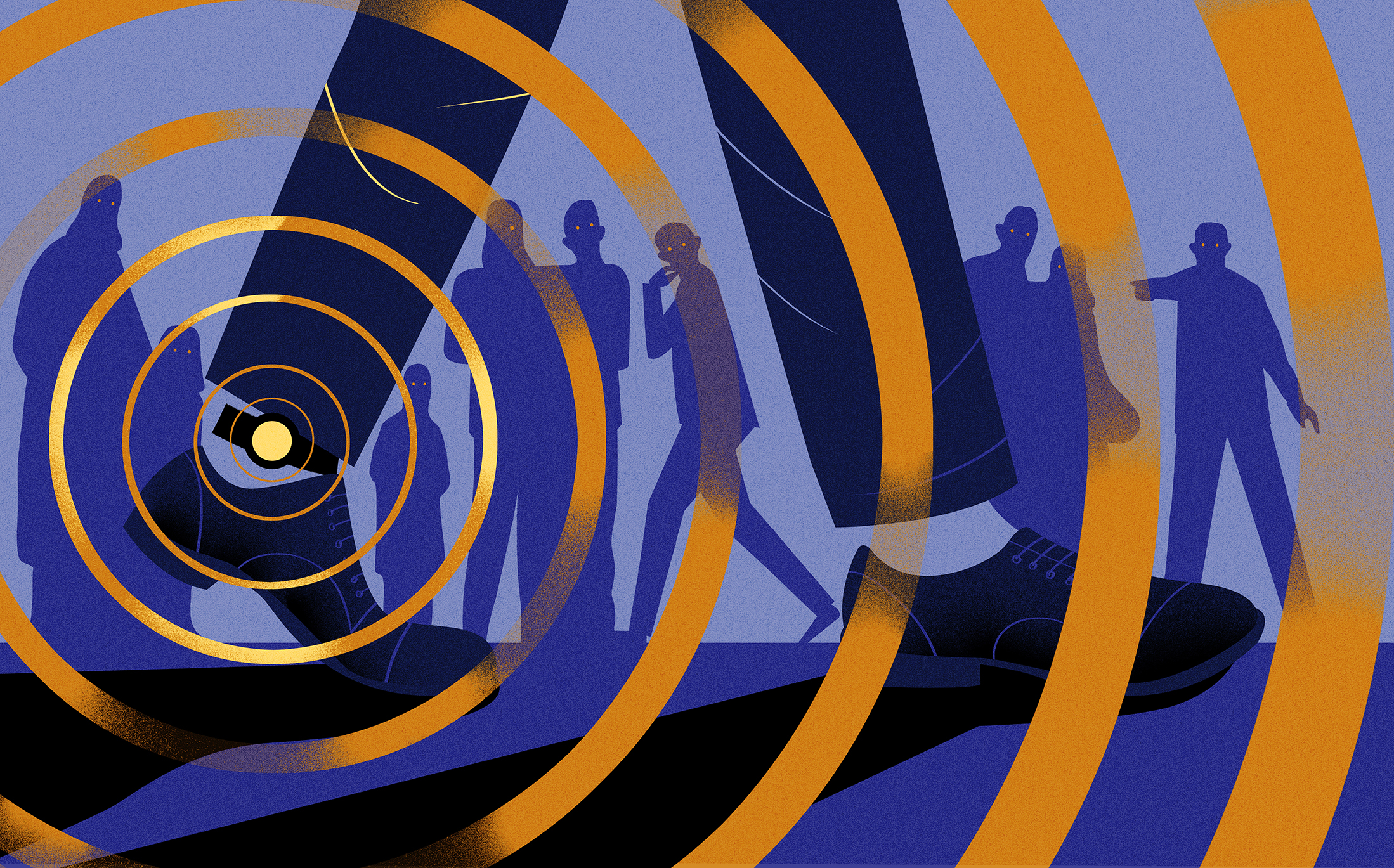

Many first-time sex offenders on the spectrum may not understand the laws they break. How should their crimes be treated?

F

or years, Nick Dubin couldn’t bring himself to say the word ‘gay,’ but part of him wondered: Was he gay? Dubin has autism. And growing up in the suburbs of Detroit, Michigan, he had been mercilessly taunted by his peers, some of whom had called him gay simply because he was different.But what if he actually was homosexual? As an adult, Dubin found some men attractive, and his attempts at dating women had not gone well. To help him understand his sexuality, Dubin recalls, a therapist he was seeing in 2010 suggested he buy a few adult pornography magazines. Dubin is soft-spoken and comes across as earnest, and he took the therapist’s advice seriously. He drove to a seedy part of the city and purchased a handful of magazines. He also began looking at pornography on the internet. He recalls being surprised that it was free and so easy to find. Soon he was bombarded with pop-up ads for porn sites. Some of the ads he clicked on led to sites with pictures of minors, which he downloaded to his computer.

At the time, Dubin was 33 and had built an impressive career as an autism advocate. He had a doctorate in psychology and was working as a consultant in a nearby school for autistic students. By all appearances, he was someone who should have known that child pornography is wrong. “This is what’s often confusing to people who have not dealt with autism spectrum [disorder] before,” Lynda Geller, a New York City-based psychologist and autism specialist, said at a conference on the topic in Rochester, Michigan, in May. “They see before them someone that they’re talking with who seems quite bright, and yet whose social intelligence is quite different than their intellectual intelligence.”

That disconnect seemed to hold true for Dubin. One test that estimates a person’s social age revealed that he functions as a 7- to 11-year-old child. In someone with such a young social age, Geller says, the ages of children in photographs may not register as they would for a typical adult. Dubin says he has never had sexual feelings about children, and it had never occurred to him that looking at naked pictures of minors is against the law: “I had no concept of how something I was doing in the privacy of my home without interacting with anyone could be breaking the law,” he says.

This grave miscalculation changed his life forever.

Later that year, just after dawn one Wednesday, a dozen agents from the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) forced open the door of his apartment. They handcuffed him and told him they had a search warrant. Dubin thought at first that the men were from the fire department. He asked them repeatedly why they were there. “You want to tell us about something on your computer?” one agent finally said. Dubin was arrested and ultimately convicted for possessing child pornography.

Dubin is one of many autistic individuals who have become embroiled in the criminal justice system because of their sexual behavior. Some, like Dubin, have found themselves in legal trouble for viewing or collecting child pornography, whereas others have been charged with stalking, masturbating in public, harassment or sexual assault. Some are serving prison sentences. And hundreds, if not thousands — the numbers are impossible to pin down — including Dubin, have become registered sex offenders, a status that can prevent them from receiving state services and finding jobs for the rest of their lives.

Many of these autistic people may have engaged in sexual behaviors without understanding the implications of their actions or the law. People on the spectrum often have problems with social communication, awareness and experience. That, coupled with other hallmark traits associated with autism — including intense interests and repetitive behaviors, as well as sensory differences — can unwittingly cause problems when they start dating or exploring their sexuality.

For these reasons, some experts are calling for a change in how the criminal justice system treats autistic people. The 2018 sentencing guidelines for U.S. courts directly acknowledge that shorter sentences may be warranted when a defendant’s mental capacity contributes substantially to the commission of the offense. But it is not clear how that comes into play for people on the spectrum.

“There should be an escape from sex-offender registration for those with autism spectrum disorder who are first offenders with no history of inappropriate contact with children,” says Mark Mahoney, a lawyer familiar with Dubin’s case. Some studies show that registration laws generally do not have the effect of deterring sexual offenses — in part because most sex crimes are committed by relatives and acquaintances, not by strangers. And registration can have particularly devastating effects on autistic people’s lives: It further isolates and stigmatizes them, and also limits their access to services and benefits.

“I am not the type of person who would ever intentionally harm another human being,” Dubin says. His parents, lawyers and therapists agree.

In addition to legal reform, people on the spectrum would also benefit from sex education, Dubin and others say. Autistic people are much less likely than their neurotypical peers to receive any kind of sex education, either at school or at home, according to one 2015 study. And without education, sexual rules — often unspoken and riddled with nuance — can be among the most difficult to parse. “People on the autism spectrum are notoriously law-abiding rule followers,” Geller said at the conference in May. But “if they don’t know a rule, they don’t follow it.”

Lack of experience:

O

ne common and pernicious myth about autism is that it renders people asexual and unemotional, with no need for intimacy; in fact, many autistic people crave closeness, even if they struggle to foster it. In a study published in May, researchers interviewed 232 teenagers and adults on the spectrum, as well as 227 neurotypical individuals, and found that the participants with autism were just as interested in having romantic and sexual relationships as everyone else. “Despite stereotypes that autistic people do not want friendships or relationships, many do,” says Laura Graham Holmes, a clinical psychologist at the A.J. Drexel Autism Institute in Philadelphia.Yet autistic adolescent boys are less likely than their typical peers to have had sexual experiences with a partner, according to a 2016 study. And in a small study published in April, only 10 of 27 autistic adolescents and young adults interviewed said they had had any relationship experience; 7 of those 10 indicated that their relationships had been unhealthy or confusing. After Dubin graduated from college with a degree in communications in 2000, his friends started getting married, he recalls — but he hadn’t yet gone on a single date. In 2004, when he was 27, Dubin was formally diagnosed with autism, although his parents had noticed social differences from a young age.

When he finally did start dating via a web service, he didn’t have much success. He would sometimes take women out and then never hear from them again; one woman explained that she didn’t like that he preferred exchanging emails to talking with her on the phone. (Many autistic people prefer to communicate via email, in part because it gives them more time to think about and craft their responses, according to a 2016 study.)

People on the spectrum can also find courtship signals and expectations difficult to pick up on, says Jessica Penwell Barnett, a sociologist at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio, who studies sexuality among people with disabilities. She recounts the story of one autistic man who told her about a disastrous date: A woman had asked him to spend the night with her. He agreed, but the following morning she was clearly irritated, and he could not understand why. He had not realized, as a neurotypical friend explained to him the next day, that she had probably expected him not only to sleep there but also to initiate sex — something he happily would have done if he had only known.

Autistic people “often don’t get cues that neurotypical people think that they’re sending them, because they’re not clear and direct,” Barnett says. That makes flirting and asking others out difficult to master. “[They] are more likely to do things like follow a person around rather than walk up and initiate a conversation.”

The converse is also true. People with autism may not always get the message that someone is signaling disinterest — by ignoring their phone calls or by saying they’re too busy to go out. If they miss these subtle hints, they may come across as creepy or persistent, and perhaps be accused of stalking or harassment: They often pursue romantic interests for much longer than others do, even after the object of their affection rejects them, according to one 2007 study.

They are also more likely than typical people to be especially sensitive to sensory information or to seek more stimulation; this, too, can lead to inappropriate behavior. Dubin, for instance, sought tactile stimulation from a young age. He liked to touch people on the head because he liked the feeling of their hair; only when he got older did he learn it was inappropriate. These kinds of sensory issues contribute to offending behavior, according to a small unpublished study presented at this year’s annual meeting of the International Society for Autism Research.

The actions of autistic people can be interpreted as sexual even when they are not intended that way — a phenomenon sometimes referred to as ‘counterfeit deviance.’ Psychologist Gary Mesibov recalls one striking case from decades ago in which a woman in North Carolina accused a young autistic man of stalking her; he said his intention had instead been to protect her. He had read about sexual assaults in the local newspaper and had become worried for her safety. “He decided that he needed to watch over her,” says Mesibov, former director of the TEACCH Autism Program at the University of North Carolina, who consulted on the case. The man began following the woman on her walk home from work in the evenings and waiting outside her home in the mornings.

The story illustrates the importance of ‘theory of mind’ — the ability to put oneself in another person’s shoes — in modulating sexual behavior. Many autistic individuals have trouble with this skill. With better skills, this young man might have realized that his behavior came across as threatening — and terrifying — to the woman he had been following.

Dubin says his own problems with theory of mind meant he never considered how the children in the pornographic images he viewed got there or whether they might have been abused. (None of the photos he viewed showed abuse, he says.) At the Rochester conference in May, Mahoney explained that when most people see child pornography, “they’re seeing it with this wealth of social understanding that’s developed over their entire life, of thousands of social interactions, thousands of cues as to what’s acceptable or not to society.” But autistic people may not share this socialized perspective; they might zero in on body parts and literally “not see the social context of a photograph.” Once his therapist explained to Dubin the violence inherent in the production of child pornography, Dubin says he was mortified. “I truly was blind to the harm I was causing,” he says. “But that doesn’t mean I wasn’t causing harm, and I sincerely wish I could turn back time and do better with the information I have now.”

Missing information:

T

he neurological differences and communication problems that underpin autism are not the only potential contributors to inappropriate sexual behavior. Most typical individuals learn appropriate courtship behavior from their peers, but many autistic people don’t have meaningful friendships growing up. “They don’t have anybody to talk to in the locker room,” says Brian Kelmar, co-founder of the nonprofit Legal Reform for People Intellectually and Developmentally Disabled, based in Richmond, Virginia.That lack of knowledge landed Kelmar’s autistic son ‘Eric’ (his real name is being withheld to protect his privacy) in trouble in 2010 after he began receiving sexual texts from a girl several years younger than him. At the time, Eric didn’t understand the implications of her texts and agreed to meet her, thinking he had made a new friend. The girl initiated oral sex, Kelmar says, at which point Eric — who was extremely sensitive to touch — froze and asked her to stop. They parted ways. That night, however, police showed up at Kelmar’s front door and arrested his son for sexually assaulting a minor. Eric didn’t spend time in prison, but he was added to the sex offender registry indefinitely. “If it were not for his age and gender, he would be regarded as the victim,” says Mahoney, who is familiar with the case.

Sex education might have helped Kelmar’s son, but it is “deplorably absent” for young people on the spectrum, sociologist Barnett says. In a 2014 survey, less than half as many autistic adults as controls said their parents and teachers had talked to them about sex. “A lot of folks on the spectrum are in secluded classrooms, which very often never offered any form of sexuality education,” Barnett says. And often, “parents feel that sexuality, and therefore sexuality education, are inappropriate for their autistic child.”

To counteract the problem, the Organization for Autism Research in May published an online sex-education module for autistic people 15 years old and up. Kelmar is also introducing legislation in Virginia that would require sex education for students with intellectual disabilities. And at last year’s meeting of the International Society for Autism Research, researchers and autism advocates met to develop a research agenda around sexuality and romantic relationships, and to better understand what autistic people need in terms of support and education.

Dubin also didn’t have much sex education — nor did he learn much from his peers. As he recalls, he was “friendless from middle school on”: He went home every day for lunch because he never had anyone to sit with in the school cafeteria; without friends, it was much more difficult for him to learn the basics of flirting, dating and sex, and to discuss burgeoning feelings about his sexuality. “I don’t say this to blame my autism or make excuses,” Dubin says, but if he had had “same-age friends to confide my thoughts and feelings to, it would have made a difference.” Starved of healthy social interactions, Holmes says, people on the spectrum often end up learning sexual scripts and norms “from less credible sources like media — which depicts all kinds of unhealthy relationship behavior — or pornography.”

Aside from providing information, pornography can be attractive to autistic teenagers and young adults for another reason: Its networks provide them with a social outlet, making them feel liked and accepted. Mesibov once worked with a 15-year-old autistic boy who went to prison for sharing child pornography. The boy had been encouraged by online predators to join child porn chat rooms, where he felt appreciated and included. “They’re not only sexually frustrated, but they’re socially frustrated,” Mesibov says. In chat rooms, “they’re not just getting hooked on looking at more pictures, but they’re getting hooked on a social interaction.”

Life after crime:

T

he day after Dubin’s apartment was raided, he was formally charged in a Detroit courthouse and an electronic tether was bound to his ankle to record his every movement while he awaited trial. He was required to stay in his apartment between 8 p.m. and 8 a.m. every day and was ordered to attend a weekly sex-offender therapy group. The expectations of group therapy — having to engage socially and share personal details with strangers who were also sex offenders — made him extremely anxious, and the information he got from the group was confusing, too. According to Dubin, the group leader told him that by being open and honest, he could shorten his sentence, but privately, people in the group told him that anything he said could be used against him in court.Dubin’s father, a lawyer, marshaled an impressive defense team, including former prosecutor Alan Gershel, chief of the criminal justice division at the U.S. Attorney’s office in Detroit from 1989 to 2008. The defense team requested a pretrial diversion — meaning Dubin’s criminal charges would be dropped and he would instead undergo what is typically an 18-month-long period of supervision by the U.S. Probation and Pretrial Services System. The prosecution refused.

The prosecution requested an independent evaluation of Dubin’s mental health. The independent forensic psychologist concluded that Dubin was not likely to be a threat to children and recommended against “impediments,” such as sex offender registration, that might “limit [Dubin’s] access to social support and opportunities for social learning.” Even so, Dubin was convicted of a felony. He did not go to prison but was required to register as a sex offender.

Life on the sex offender registry is never easy, but it can be especially difficult for someone on the spectrum. “It destroys these kids’ lives,” Kelmar says. First, the registry comes with residence restrictions — in some states, offenders cannot live within 1,000 feet of a school or places where children congregate. Erin Comartin, associate professor of social work at Wayne State University in Detroit, once calculated that there were only two homes in all of Ferndale, Michigan, a suburb near where Dubin resides, in which sex offenders are legally allowed to live. Because many autistic people live with their parents, these residency requirements often mean the entire family is forced to move. “It takes over their families, it takes over their lives,” Comartin said at the Rochester conference.

The registry also makes it more difficult for people with autism to get jobs than it already is. Yet at the same time, anyone on the sex offender registry is ineligible for ‘Section 8’ housing assistance, which subsidizes housing costs for people who make less than a certain income.

In what may be the worst possible outcome, autistic sex offenders can also end up in prison. Sentences for child pornography have skyrocketed in recent years; they averaged 34 months in 2004, but 66 months in 2013. And for people on the spectrum, long spells in prison can be more difficult because of their sensitivities to light and sound, and the social demands of sharing a prison cell, according to “The Science of Evil,” a 2011 book by Simon Baron-Cohen, director of the University of Cambridge’s Autism Research Centre. Putting someone with autism behind bars is like “dropping a wheelchair-bound individual with physical disabilities into a swimming pool and expecting them to cope,” he wrote.

At the conference, a man named Tom, who asked to be referred to by his first name only, choked up when describing the day he had had to drive his autistic son to prison after a child pornography conviction. “It’s way too painful for me to tell you what I was feeling inside,” he said. “After dropping off my son at the gates of prison, I drove a few miles away, pulled off the road and cried like I’ve never cried before in my life.”

Mahoney says one of his autistic clients, who spent nearly two-and-a-half years in prison for possessing child pornography, has attempted suicide several times since he was released. “He cannot get work, he cannot get services, he cannot get [Section 8 housing choice] vouchers for living expenses, they will not let him in temple,” Mahoney says. The client feels, Mahoney says, like “he has nothing to live for except his dog.”

Mahoney and others argue that autistic people who are first-time sex offenders and have had no inappropriate contact with children should not spend time in prison or be put on the registry. A few researchers and organizations, including the Organization for Autism Research and the Asperger/Autism Network, have co-signed a set of guidelines that include this recommendation. And they are making progress on this front. At the Rochester conference, Mahoney said there were eight cases he knew of in federal courts in which prosecutors had allowed individuals on the spectrum to plead guilty to offenses without requiring prison time or registration, or had agreed to pretrial diversions.

When evaluating cases, “there should be an assessment of contributing factors, such as co-occurring conditions, and a focus on remediation: education on laws, treatment for executive impairments, treatment for co-occurring conditions, and cognitive behavioral therapy focused on offending behaviors,” Holmes says.

Autistic people should also be exempt from the usual treatments for sex offenders, Mahoney and others say. These treatments typically involve rehabilitating deviant thoughts and correcting aberrant beliefs about sexuality — but what people on the spectrum need instead is basic information about what is appropriate and what is not, which they may never have been given before. “What we recommend is that the [sex] education happen early and that it be lifelong,” Barnett says.

Dubin, now 42, has had ongoing therapy and education, and has spent the past nine years trying to atone for his mistakes. In 2014, he co-wrote “The Autism Spectrum, Sexuality and the Law,” which tells his life story and provides information and advice for parents, psychologists and criminal-justice professionals. He also regularly speaks at conferences about autism, sex education and sexuality — he has realized that he is, in fact, gay — hoping to help other autistic people understand the consequences and moral implications of poor decisions like his own: “I’ve spent every day of my life since 2010 thinking about that.”

Corrections

This article has been revised. The original incorrectly stated that Nick Dubin views children and teenagers as his peers.

Syndication

This article was republished in Slate.

Recommended reading

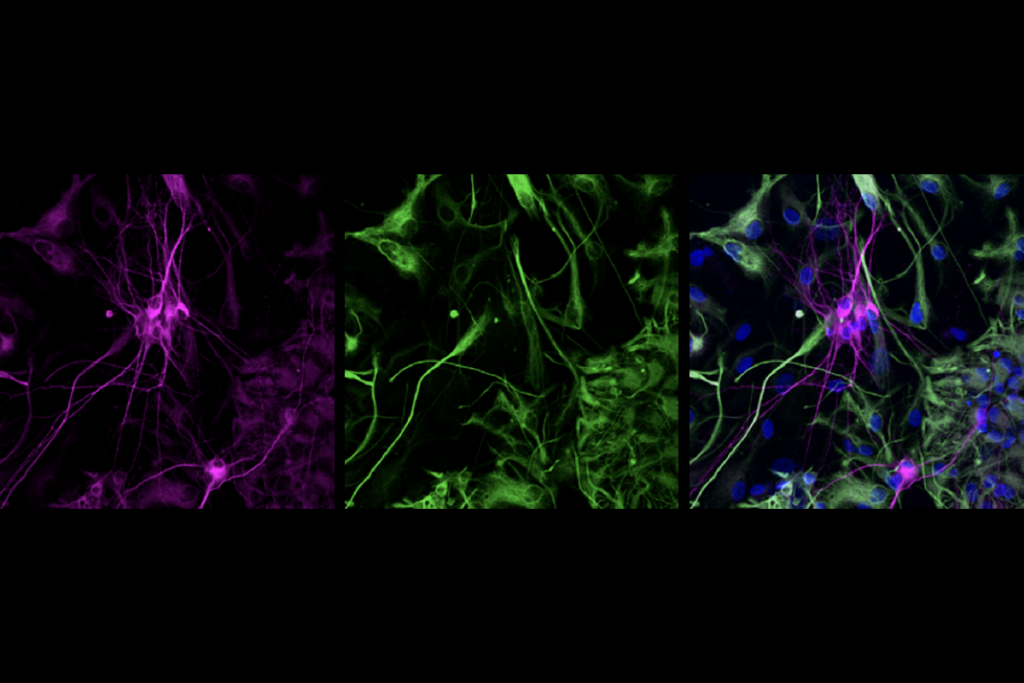

Parsing phenotypes in people with shared autism-linked variants; and more

Boosting SCN2A expression reduces seizures in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

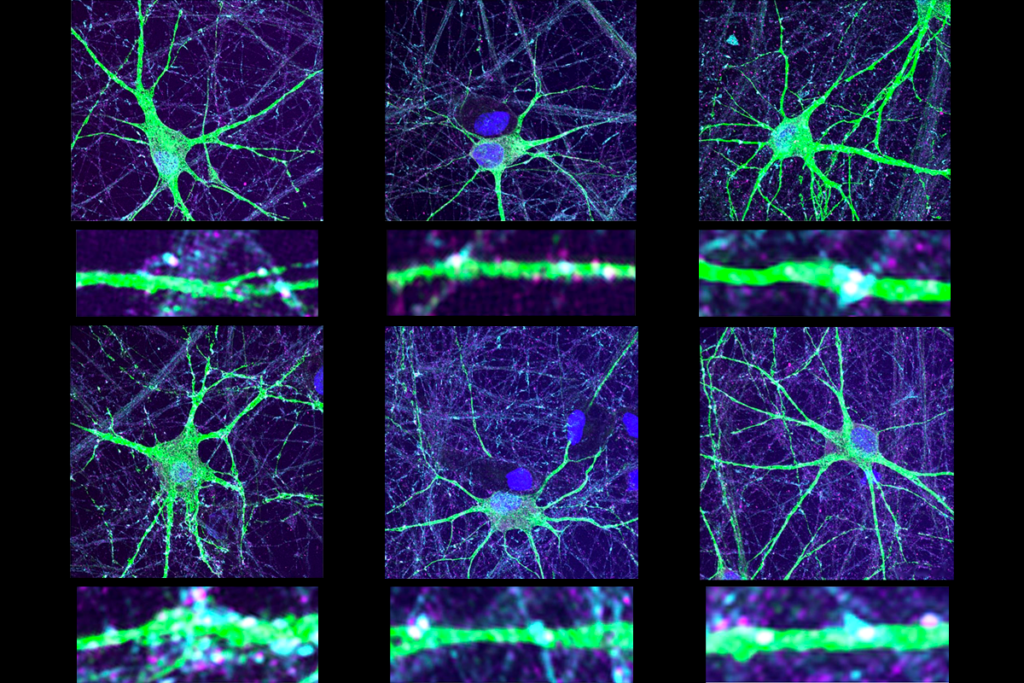

Engrams in amygdala lean on astrocytes to solidify memories

Ant olfactory neurons reveal new ‘transcriptional shield’ mechanism of gene regulation