Cracking the neural code for emotional states

Rather than act as a simple switchboard for innate behaviors, the hypothalamus encodes an animal’s internal state, which influences behavior.

Nestled in the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus lies a cluster of neurons that can make otherwise mild-mannered mice fly into a rage. Stimulating these neurons, as if flipping a switch, prompts male mice to attack their cagemates.

The optogenetic manipulation of these and other specialized hypothalamic neurons, starting in the early 2010s, supported the long-standing idea that distinct cell types act as an “on” switch for different innate behaviors.

But it has proved challenging to disentangle the neural signals that underlie those innate behaviors from ones that drive an animal’s internal state—such as anger, hunger or sexual arousal.

Mounting evidence suggests that the hypothalamus also gives rise to these internal states, which can shape innate perceptions and behaviors. Rather than triggering an innate behavior, a specific pattern of population activity encodes the intensity and duration of anger and sexual arousal, according to four studies published within the past three years.

This work is “revolutionary for the hypothalamus community,” says Tatiana Engel, associate professor of computational neuroscience at the Princeton Neuroscience Institute, who was not involved in the studies. It upends the notion that the neurons in the hypothalamus merely act as a simple switchboard, Engel says. Instead, local computations in the hypothalamus keep track of the animal’s internal state and influence its behavior, the studies suggest.

The hypothalamic signals that encode the intensity and duration of aggression and sexual arousal can be represented by a mathematical model called a line attractor, the four studies show.

“While attractors have been described for over a decade as representing cognitive variables, such as memories or head direction, they were thought to only play a role in encoding cognition,” says David Anderson, professor of biology at the California Institute of Technology, who is an investigator on all four studies. “The brain mechanisms underlying cognition and emotion might actually be more closely related than people have thought.”

N

Variable and persistent neural activity in the cortex and hippocampus has been modeled using dynamical systems, specifically attractor networks. “If you think of neural activity in the brain as a topographic landscape,” in which each point reflects the collective activity of millions of neurons, “that landscape has hills and valleys. Attractors are those features like pits and valleys that are sticky” and difficult to change, Anderson says.

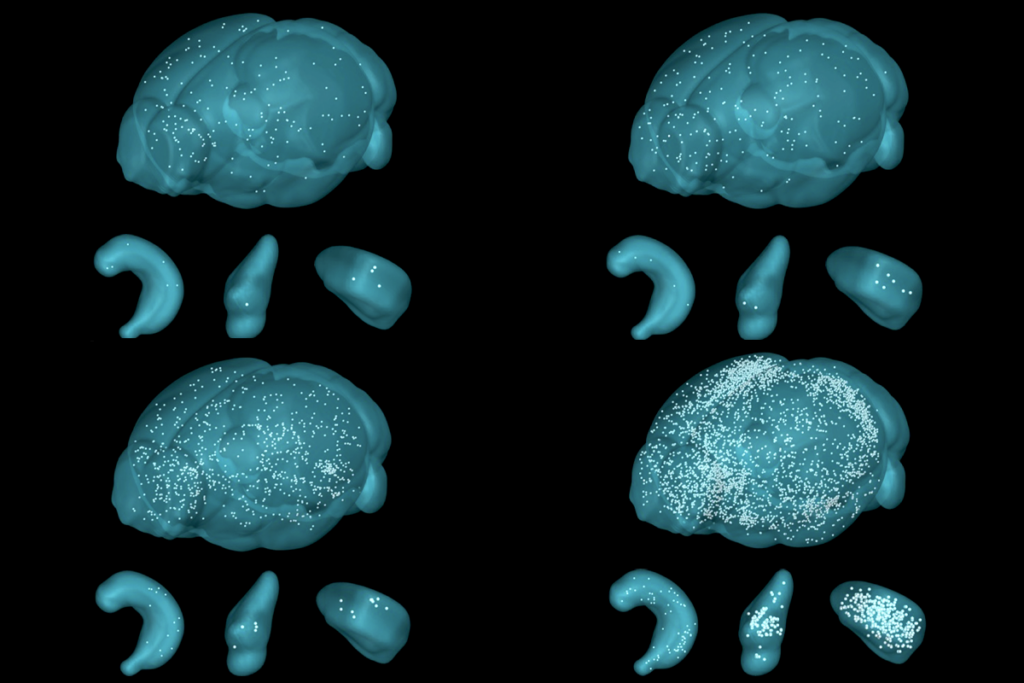

Anderson and his colleagues sought to model hypothalamus activity using a dynamical systems perspective after they recorded the activity of thousands of the supposedly aggression-specific neurons—those that express ESR1 in the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus—in freely moving male mice as they encountered and attacked an unfamiliar male mouse in their home cages. The ESR1 neurons didn’t consistently fire while a mouse was behaving aggressively, the team discovered, hinting that the region’s collective activity, rather than any individual neuron, encodes the behavior.

Applying dimensionality reduction techniques to the data revealed a latent, or hidden, stable activity pattern, the team reported in a 2023 study. The dynamics of the neuronal firing generated a line attractor, which looks like a long, shallow gully in a hilly landscape. The gully comprises a range of stable, slightly different patterns of population activity. It allows the neural circuit to keep track of a variable that increases or decreases in intensity, like a volume knob.

This line attractor-like activity pattern appears as soon as a mouse picks up the scent of an intruder, Anderson’s team found. As the mouse’s level of aggression increases, neural activity moves along the floor of the gully. And the neural activity stays in the line attractor-like state even after the intruder mouse leaves.

If the neural activity simply encoded the behavior, “it would have jumped out of the gully every time the mouse stopped attacking,” Anderson says. Instead, the activity remained in the gully, suggesting that it encoded an internal state.

ESR1 neurons in mice viewing aggressive interactions also generated an approximate line attractor, indicating that the activity was not a consequence of fighting behavior. Optogenetically reactivating the neurons that contribute to the line attractor, even when mice were no longer viewing the interaction, slowly drove the population into a line attractor-like state, leading to persistent network activity that decayed slowly, the team reported in a 2024 study. The results indicate that ESR1 neurons form an interconnected circuit that has slow decay dynamics and that integrates information over time. Optogenetically activating individual neurons that contribute to the line attractor elicited activity in nearby neurons in the attractor network.

Although the mice in this study were head-fixed and could not attack, the results provide the first causal evidence that ESR1 neurons located in the hypothalamus encode internal states, Anderson says.

“These were really amazing experiments,” says Juan Gallego, a group leader at the Champalimaud Foundation, who was not involved in the work. “They probed causally what they could infer with neural recordings” in a precise manner, and “that’s pretty rare.” Studies that model cortical activity have not found specific cell types performing specific functions, as Anderson and his team have in the hypothalamus, Gallego says, successfully bridging theoretical modeling of neural population activity and its implementation by biological circuits.

But “my intuition is it won’t be that easy to bias decisions or actions by optogenetically stimulating the cortex,” Gallego adds. “You don’t find this clear mapping between dimensions in the manifold and single neurons.”

Because the neural signals for aggressiveness persist for minutes, slow-acting chemical messengers such as oxytocin and vasopressin might be involved, the team hypothesized. Indeed, disrupting ESR1 neurons’ ability to detect oxytocin and vasopressin by way of CRISPR prevented the formation of the aggression line attractor, the team reported in an additional 2024 paper. The animals showed reduced aggression, and this manipulation dampened the activity of neurons in the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus following an aggression-promoting stimulus, Anderson says.

In female mice, ESR1 neurons encode sexual arousal with an approximate line attractor, according to another 2024 study from Anderson’s team. Neural activity moves along the attractor over the course of an encounter, the study shows. This attractor requires estrogen and progesterone, so it forms only during certain parts of the estrus cycle when females are sexually receptive. These results show that the line attractor mechanism of encoding information is generalizable and malleable, Anderson says.

Taken together, the four papers provide the first neural dynamics perspective of the hypothalamus, grounded in “careful experimental data,” says Vivek Jayaraman, senior group leader at Janelia Research Campus of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, who was not involved in the studies.

A

The phenomenon of “hangriness” has not previously been described in mice. The literature suggests that starvation makes mice less aggressive, Anderson says. But when he and his colleagues varied the amount of time that the mice went without food, they found a horseshoe-shaped relationship between hunger and aggression: Mice deprived of food become more aggressive up to the point of starvation, after which aggression decreases.

In an individual mouse, the level of hangriness affects the shape of the aggression line attractor, the preprint shows. Neural populations in hangry mice enter the line attractor more rapidly than in sated mice. And when their activity enters the line attractor state, it “rolls” down the gully more slowly than in sated mice. Hangry mice were also quicker to attack an intruder than are sated mice.

By contrast, starvation eliminated the line attractor entirely, the preprint shows. This makes sense evolutionarily, Anderson says—if a mouse is starving, it is not beneficial for it to use its remaining energy to fight.

Although the researchers traced the aggression attractor causally to ESR1 neurons, the molecular mechanisms that enable the neurons to integrate information over time, as well as their downstream connectivity, remain unclear. “There must be other neurons in the brain listening to the attractor and extracting information,” Anderson says. “We have to find out where those neurons are, what information they’re extracting and how they’re converting it.”

Future studies still need to determine whether attractor dynamics govern rage, sexual arousal and other emotional states in people. If emotions are encoded in this way, it’s possible that long-lasting neuropsychiatric conditions, such as depression, are due to neural activity being “stuck” in a metaphorical valley, Anderson says. Disrupting these neural dynamics could represent a new therapeutic strategy, he adds.

Recommended reading

Remembering Adam Kampff, neuroscience educator and researcher

Neuroscience needs engineers—for more reasons than you think

The challenge of defining a neural population

Explore more from The Transmitter

Sex hormone boosts female rats’ sensitivity to unexpected rewards