NIH proposal sows concerns over future of animal research, unnecessary costs

The new NIH policy calls for greater incorporation of new approach methodologies in all future Notices of Funding Opportunities related to animal model systems.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced last week that its future funding opportunities would no longer include research that exclusively uses animal models, confusing members of the neuroscience community.

The announcement has researchers wondering exactly what the mandate entails, if it applies to all grant proposals and even how it might affect the future of animal research, says Eliza Bliss-Moreau, professor of psychology at the University of California Davis. “I don’t have an understanding of the policy, and I think that’s part of the challenge.”

During the FDA & NIH Workshop on Reducing Animal Testing on 7 July, Nicole C. Kleinstreuer, acting NIH Deputy Director for Program Coordination, Planning and Strategic Initiatives, said that “all new NIH funding opportunities moving forward should incorporate language on consideration of [new approach methodologies],” adding that “NIH will no longer seek proposals exclusively for animal models.” In a press release published 10 July, NIH clarified that all funding opportunities related to animal model systems “must now also support human-focused approaches such as clinical trials, real world data, or new approach methods (NAMs).”

Yet, the announcement doesn’t make clear which animal models are included and whether a proposal without NAMs is automatically denied, says Nicole Ackermans, professor of biological sciences at the University of Alabama. It also raises the issue of what this means for the future of animal research. “Is the goal to have zero animal research in the United States, and at what point in time? Is that immediate or is that over the next 50 years?” she says. “How would you support the transition financially to get there? Because it will be expensive.”

There is also uncertainty about how NIH will implement the policy. Already, researchers are encouraged to consider alternative methods—when possible—and then include their justification for animal use in grant proposals, says Takashi Kozai, associate professor of bioengineering at the University of Pittsburgh. Being required to include NAMs in all grant proposals for notice of funding opportunities (NOFOs) would add “an additional layer of work, and an unclear review path that’s going to add a lot of uncertainty.”

This is the most recent move in a series of developments to prioritize “human-based research technologies,” particularly NAMs, which include organoids, computational models and non-mammalian models, among other approaches. In April, the FDA announced a plan to phase out animal research.

NIH has not published a final policy and did not respond to specific questions but did email The Transmitter to say that “all future funding announcements will emphasize human-relevant data such as clinical trials and real-world data, and new approach methods (NAMs) such as advanced laboratory-based methods and AI-driven tools.” The agency added that in order to “support NIH’s shift toward human-focused research, NIH will no longer issue NOFOs exclusively for animal models, and some may exclude animal use entirely, advancing science that directly benefits human health.”

While researchers can obtain NIH funding through other avenues, such as supplemental grants, NOFOs are a main mechanism through which NIH directs policy, priorities and research directions, Ackermans says.

N

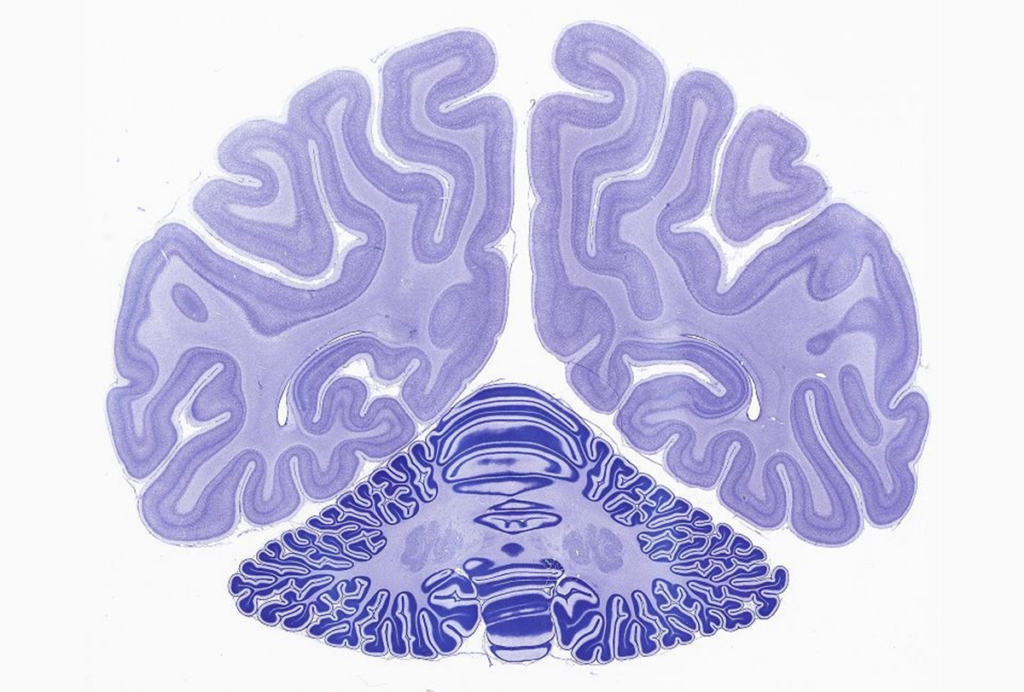

IH first signaled a shift away from animal research with the NIH Revitalization Act in 1993. More recently, NIH has been pushing NAMs (which have also been called novel alternative methods, non-animal methods, or new alternative methods) to complement animal research, and many neuroscientists welcome the use of models that reduce animal testing. As for the new policy, these include “ex vivo human-based approaches, including perfused human organs and precision-cut tissue slices; in vitro methods, including microphysiological systems and organoids; computational and artificial intelligence-based approaches; and combinations thereof.” Still, some of the alternative approaches are “very premature,” says Kozai.A push toward phasing out animal research now would be a “disaster” for neuroscience researchers specifically, since many rely on mouse and non-human primate models exclusively, says Arnold Kriegstein, professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, who had been a part of an NIH-commissioned 2023 report on alternative models.

Particularly in neuroscience, some NAMs are not yet thoroughly validated and might be too simplistic or insufficient to answer basic questions about the brain and behavior, he adds. For example, Kriegstein says that it would be difficult to envision how NAMs “could complement work that involves that whole animal circuit and behavior study.”

If NAMs aren’t useful for select neuroscience experiments, labs could be wasting funding, time and resources to investigate, learn and use a non-animal model just to fulfill an NIH requirement, says Bliss-Moreau. “I can imagine a situation where grants that are including [NAMs], they kind of tick the box because they include them, but the science is actually weakened because of the practical issues.”

Kriegstein says that it might be more fruitful for neuroscience if NIH called for proposals investigating alternative models themselves. “Directing funding in that direction and encouraging those applications would move the field forward much, much more quickly.”

During last week’s workshop, Kleinstreuer also said that NIH is “developing long-term solutions that ensure that there are no new animal labs that open up in their place.” This, Bliss-Moreau says, makes it seem like NIH is “abolitionist relative to the use of animals in research.”

Increasing the use of NAMs might be “the right direction eventually,” Kozai says, “but the technology isn’t there and implementing it now is going to do more harm than good.”

Recommended reading

Nonhuman primate research to lose federal funding at major European facility

Star-responsive neurons steer moths’ long-distance migration

Explore more from The Transmitter

Imagining the ultimate systems neuroscience paper

Grace Hwang and Joe Monaco discuss the future of NeuroAI