More than 200 published studies and at least seven ongoing clinical trials rely on potentially faulty brain network maps, according to a study published today in Nature Neuroscience.

The findings cast doubt on a widely used method to generate brain network maps, says František Váša, senior lecturer in machine learning and computational neuroscience at King’s College London, who was not involved in the new study and has not used the approach in his own work. “I think it’s worth revisiting some of the literature critically,” he says. And for those who use the method or plan to, “proceed with caution,” he adds.

The creators of the method, called lesion network mapping (LNM), say that the issues raised by the new study are not insurmountable. The study’s “results are often striking and tell an important cautionary point—that lesion network mapping can be prone to false-positive findings or nonspecific findings, and study designs need to be constructed carefully in a way that can account for this,” wrote LNM co-developer Aaron Boes, professor of pediatrics at the University of Iowa’s Carver College of Medicine, in an email to The Transmitter.

Boes and his colleagues developed LNM in 2015 to identify the pattern of brain activity disrupted in a given neurological condition, whether obsessive-compulsive disorder, Parkinson’s disease or psychopathy. It spawned a new way to put functional MRI to practical use, offering a clear brain network to target for treatment, says Martijn van den Heuvel, professor of computational neuroimaging and brain systems at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and an investigator on the new study.

Over the past decade, studies using LNM have produced dozens of networks that purportedly underlie individual conditions or traits, including depression, religious fundamentalism and the location of gliomas. Other investigations tested whether manipulating a given network via transcranial magnetic stimulation or deep brain stimulation could alleviate neuropsychiatric symptoms, yielding mixed results. And despite a 2020 paper questioning the method’s ability to predict behavioral issues from lesions, some treatment regimens based on LNM have entered into clinical trials.

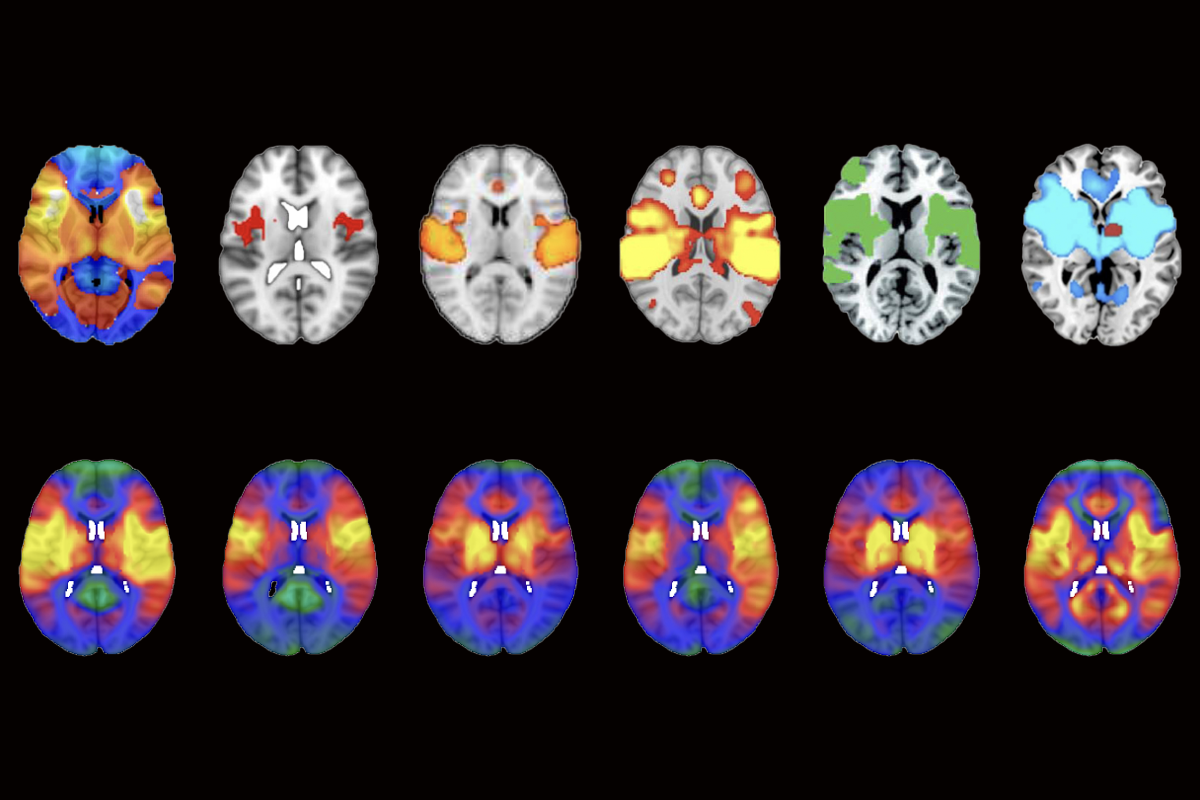

But networks identified using LNM are, for the most part, not rooted in a condition’s biology, according to the new study. Instead, a mathematical flaw in the method causes the approach to produce a nearly identical network map for any given dataset, the new study suggests.

That means that LNM’s targets are unreliable, says Sophia Frangou, professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who was not involved in the new study. “Some of the time they will be correct, by accident. But most of the time, what you think is the optimal target, it really isn’t.”

Such debate will move the field forward, wrote LNM co-investigator, Michael D. Fox, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, in an email to The Transmitter. Still, Fox added, “as a clinician, the most important test of any brain mapping method is whether it can be used to help patients, which is not tested in this methods paper but is being tested in multiple clinical trials.”

V

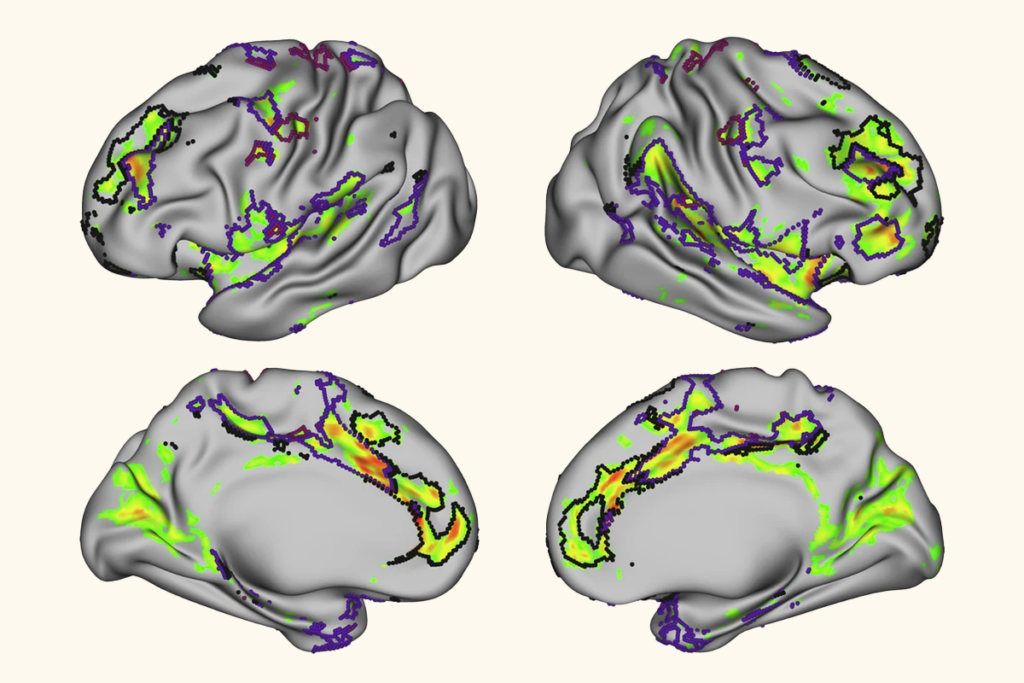

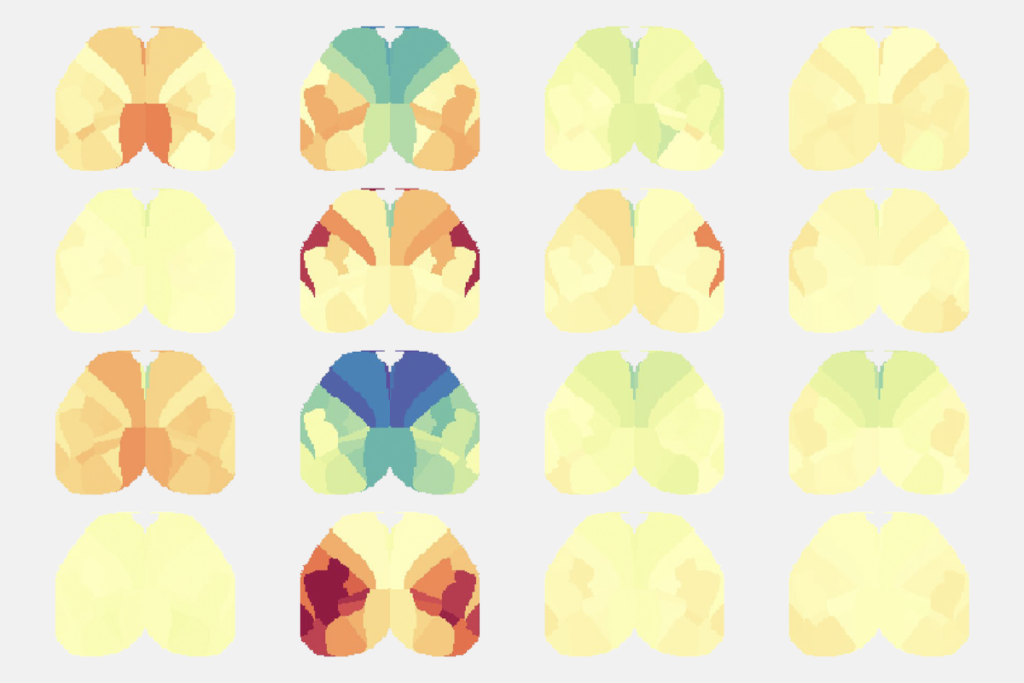

Van den Heuvel pored over other papers on LNM and repeatedly turned up the same map: The networks altered in psychosis and smoking addiction were also altered in post-traumatic stress disorder, migraine, insomnia, vertigo, and so on. All of these conditions show activation of the insular cortex, anterior cingulate cortex and the frontal cortex, he found.

Some network overlap could make sense, van den Heuvel says. For example, people with schizophrenia are more likely than average to smoke. And the overlap could reflect shared etiology among these conditions. But other connections seemed more tenuous, van den Heuvel says. “I could never find a link between psychosis and migraine, right?”

The link, van den Heuvel and his colleagues found, was in how the datasets were processed.

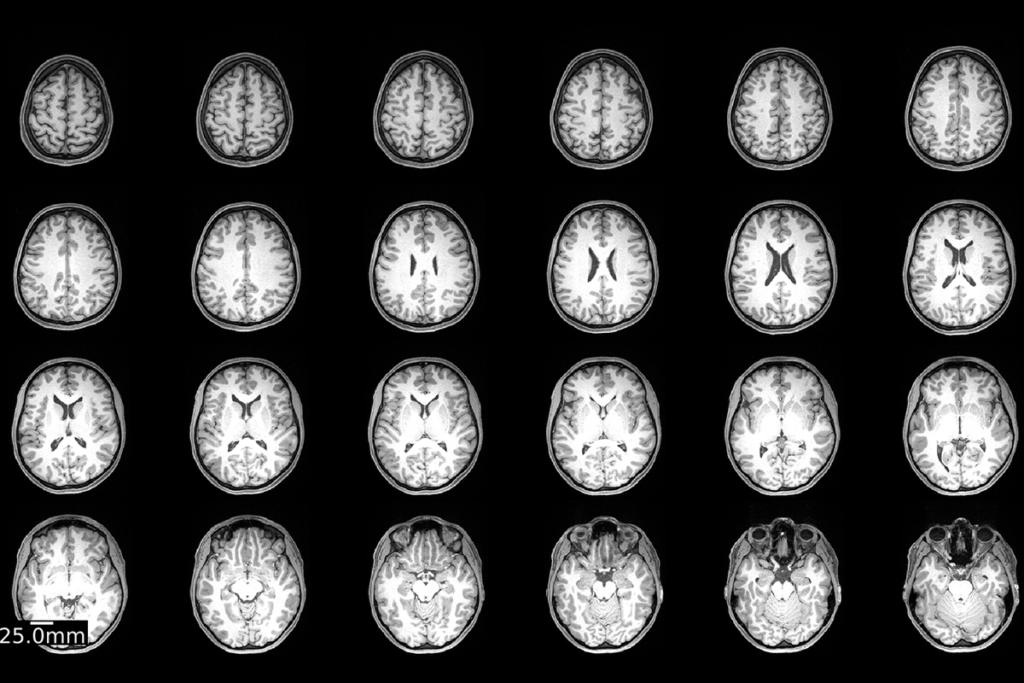

To create a lesion network map for epilepsy, for example, researchers use a reference connectome derived from healthy people to identify the networks that are likely disrupted by an epilepsy-causing lesion in a given location. They repeat the process for other participants with epilepsy who have lesions in disparate brain regions, and then they combine the affected networks to form the condition’s map. When a network within that map is disrupted by a lesion, the condition’s symptoms arise, the thinking went.

Lesion network mapping gave researchers an explanation for why two brain lesions in disparate locations could cause the same neurological condition, says Janine Bijsterbosch, associate professor of radiology at Washington University in St. Louis, who reviewed van den Heuvel’s study for Nature Neuroscience. “It was an attractive idea, and it was well received in the field.”

But each new network added to a lesion network map derives primarily from the original typical connectome, van den Heuvel and his colleagues found. That means that with each new participant and lesion, an LNM map increasingly recapitulates basic properties of the typical connectome; disorder-specific contributions to the map are minimal.

When van den Heuvel’s team applied LNM to a set of hypothetical lesions in randomized locations across the brain, the method produced essentially the same map.

“We started to realize that these networks are then likely not biological. They’re just, unfortunately, a consequence of a very complex procedure of handling data,” van den Heuvel says.

T

Because the problem stems from the data analysis, “the method itself is probably not salvageable,” Cocchi says. He adds that starting fresh with a new form of network analysis will be best for the field.

However, there may still be useful disease-specific information within maps produced by the LNM method, Váša says. “When you overlap all of these networks, they all look very similar, but they’re not identical.” It may be possible, then, to use null models to isolate statistically significant disease-specific effects, he says.

Boes and his colleagues already do that to overcome what he says was a known problem of LNMs converging to the typical connectome, he wrote in an email to The Transmitter. “Various efforts have been undertaken to address this issue, such as the use of well-matched comparison groups that share the same nonspecific patterns but differ in the elements of greatest relevance to symptom expression.” He also suggests testing LNMs by evaluating “how they perform in predicting symptoms in independent samples”—noting that his lab often sees added predictive value with the method. He said he is drafting a response letter to van den Heuvel and Cocchi’s paper.

Despite this potential way forward, the possible problems with LNM suggest that researchers should remain cautious when moving new platforms and pipelines to the clinic, Frangou says. “We have to kind of hold back in terms of the claims that we’re making, and rethink a little bit how we can personalize and optimize target detection for treatment in a way that is really scientifically very rigorous.”

And taking a step back from LNM could push researchers to explore other ways of mapping brain networks involved in neurological disorders, van den Heuvel says. “I’m absolutely certain that we will find different methods. And I think this is the silver lining.”