The big idea with Diego Bohórquez

His theories around the neuropod have challenged the boundaries of classic ideas regarding gut-brain communication.

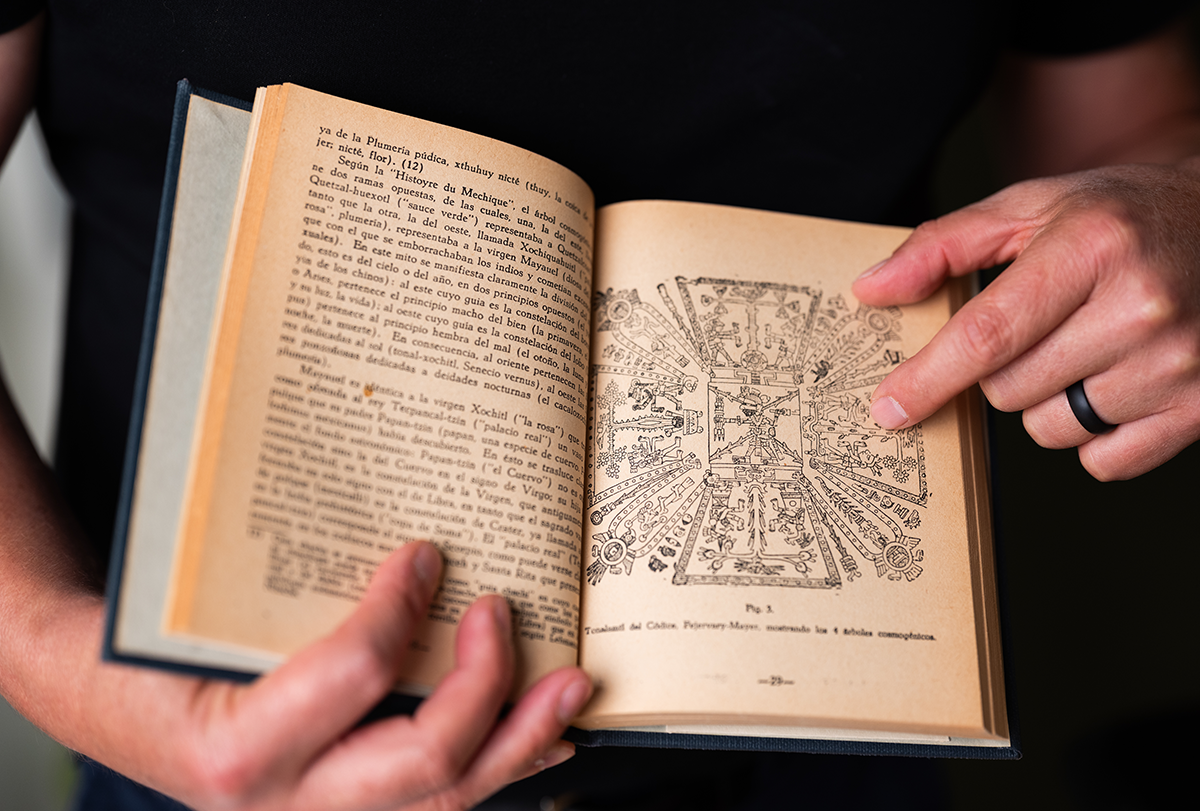

Diego Bohórquez keeps a first-edition hardback of the 1853 book “Memoirs of a Stomach,” written from the point of view of the stomach itself, in his office. He isn’t sure how he first became aware of the book, but it was mentioned in a 2015 New Yorker piece that referenced Bohórquez’s first published article.

Bohórquez, associate professor of medicine and neurobiology at Duke University, often quotes from this book, as he did in the introduction of his 2018 Science paper on the gut-brain neural circuit. He always uses roughly the same quote: “… and between myself and that individual Mr. Brain, there was established a double set of electrical wires, by which means I could, with the greatest ease and rapidity, tell him all the occurrences of the day as they arrived, and he could also impart on me his own feelings and impressions.”

“It’s just a beautiful passage,” Bohórquez says. “We were able to articulate for nearly 200 years the communication going on between the mind and the body, but we didn’t have the molecular biology.”

Bohórquez is after the molecular biology. Most notably, he examined and defined certain gut enteroendocrine cells, which he has named “neuropods,” when he was still a postdoctoral researcher. Later, he worked with his own lab to show how neuropods quickly communicate with the brain via glutamatergic signaling and influence decision-making about food.

A Perspective piece accompanying the 2018 Science paper noted that the findings “overturn a decades-old dogma that enteroendocrine cells signal exclusively through hormones,” and Kirsteen Browning, professor of neuroscience and experimental therapeutics at Pennsylvania State College of Medicine, says the work offered a “paradigm shift” for how the field considered gut-brain signaling. “I don’t think anyone had ever thought that vagal signaling from the gut might have this mechanism,” she says.

This has earned Bohórquez a reputation as a “trailblazer,” says Ivan de Araujo, director of the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics, but de Araujo notes that putting “new ideas” into a field of research is not always easy. “There will always be people saying, ‘We need more evidence.’”

B

ohórquez grew up in El Chaco, Ecuador, at the edge of the Amazon rainforest. His parents were farmers, and Bohórquez says his father traveled the country trading cattle, sometimes returning home with peacocks or horses or—one time—about 70 water buffalo. As a child, Bohórquez helped with the chores and played with the animals until, when he was 11, his parents sent him to the military school Colegio Militar Eloy Alfaro in Quito to provide him with a better education.After that, he attended Zamorano Pan-American Agricultural School, a private university in Honduras. Noticing that those in a leadership position at the university often had Ph.D.s, he began to think about graduate school in the United States. When he sought an internship in his final year at Zamorano, a faculty member helped match him with a dairy farm in California. During that spring on the farm, seven cows died in one week, and Bohórquez noted that the owner called for a nutritionist, not a veterinarian, to look into the problem. The cows were discovered to have milk fever, or low blood calcium, and Bohórquez learned their issues had “actually come from the food.”

He began to think more about nutrition. When he got back to Zamorano, a professor connected him with Peter Ferket, professor of nutrition and biotechnology at North Carolina State University, who offered Bohórquez another internship after graduation. “That’s how I landed in Raleigh, North Carolina,” Bohórquez says, “and I had to go and look it up on the map, because I had no clue where I was going.”

Ferket’s lab studies nutrition in commercial poultry, and it was Ferket who suggested that Bohórquez enroll in North Carolina State’s master’s degree program in poultry science and nutrition. A Ph.D. followed, during which Bohórquez says he took 23 courses—more than the required courseload—including biochemistry, genetics and biotechnology. The idea, he says, was to satisfy his curiosity about how the body worked and get as much out of the degree as he could.

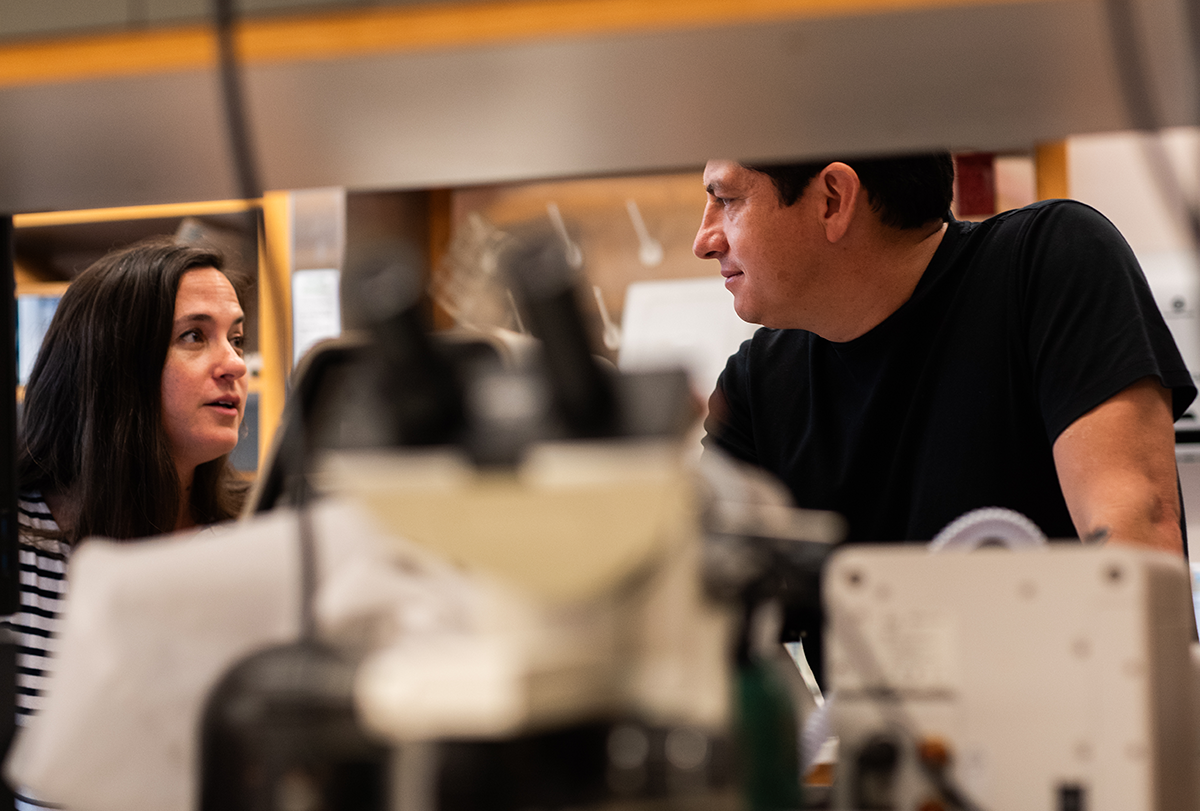

This background and training “are very different from a typical neuroscientist,” and this makes his thought process “imaginative,” says Polina Anikeeva, professor of brain and cognitive sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who has collaborated with Bohórquez.

T

wo formative things happened during his time at North Carolina State, Bohórquez says. One had to do with his graduate school project, which investigated in-ovo feeding for poultry to promote growth and improve chick health after birth. The chicks that were given nutrients in ovo were highly active and would eat robustly after hatching, he noted, whereas those not injected with nutrients in the egg tended to be sluggish. Spotting this difference got Bohórquez thinking about the link between food and behavior, he says.Around that time, he had his first Thanksgiving in the U.S. He spent the day with Ferket and his wife, Debbie, at their house. Debbie had recently undergone gastric bypass surgery, and it had changed her food preferences—before the surgery she had hated egg yolks, but afterward she craved them. Debbie was surprised by this change in behavior, and Bohórquez was, too.

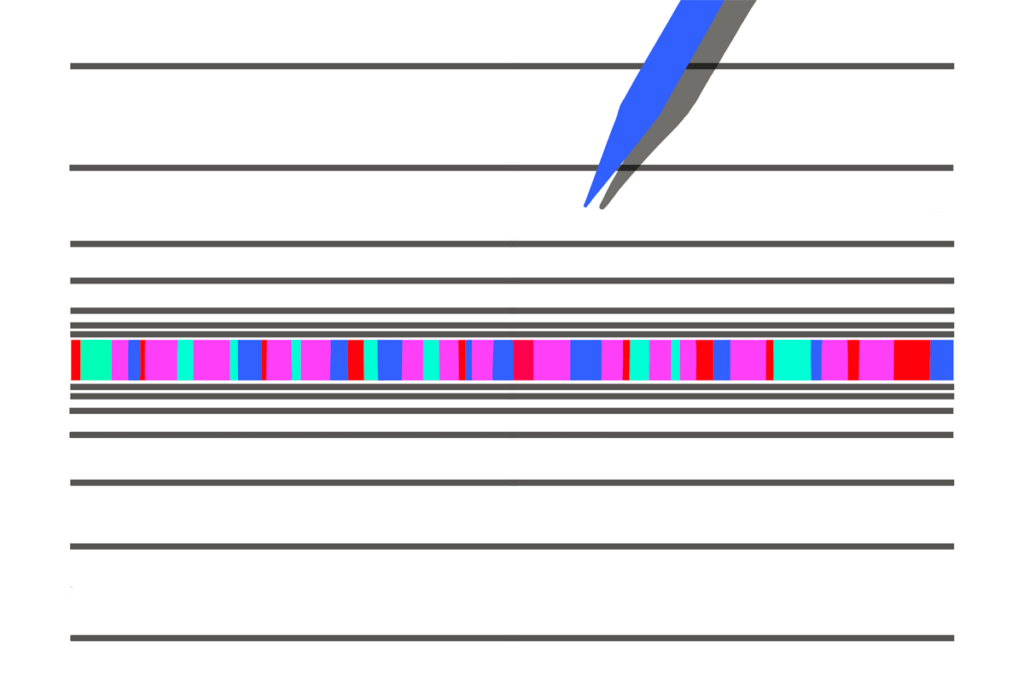

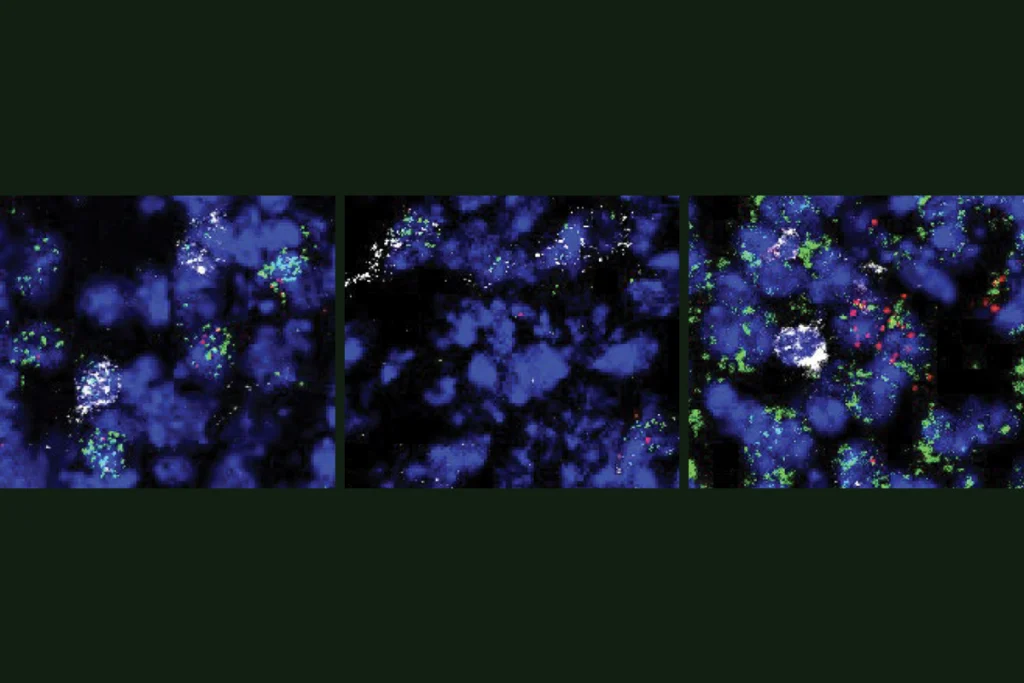

These observations led Bohórquez to study under Rodger Liddle, professor of medicine in the Duke University division of gastroenterology, for a postdoctoral fellowship in 2010. Under Liddle’s guidance, Bohórquez began studying enteroendocrine cells, which produce gut hormones. Bohórquez used serial block-face scanning electron microscopy to image sections of the enteroendocrine cells, labeling their morphological features. He also cultured an enteroendocrine cell and a nerve cell and watched as they formed a connection in the dish. Finally, to explore the nature of this connection, he injected rabies into the intestine, showing that it infected enteroendocrine cells, which in turn, infected the nervous system. That study was published in 2015 in The Journal of Clinical Investigation, essentially defining a “neuropod” as an “arm” extending from the base of some enteroendocrine cells, the other side of which faces into the lumen of the gut, allowing the cells to communicate directly with the brain.

Arthur Beyder, a consultant in the division of gastroenterology and heptology at the Mayo Clinic, points out the novelty of Bohórquez’s imaging techniques and use of rabies tracing and credits him as the first to show a synapse between enteroendocrine cells and vagal neurons. Bohórquez’s research led Beyder to wonder about the structural nature of the synaptic connections and the differences between enteroendocrine cells and tail-possessing neuropods. “I don’t think that we have strong evidence that you have to have that tail to make the synapse,” he says.

Bohórquez opened his own lab at Duke University the same year. He eventually updated the term neuropod to encompass the entire cell type, not just the extension, and in one of their first projects, he and his team used rabies tracing, polymerase chain reaction and optogenetics (among other methods) to show a direct synapse between neuropod cells and vagal neurons, with glutamate as a neurotransmitter. That became the 2018 Science paper; the work suggested “the gastrointestinal system works more or less like other sensory systems,” says de Araujo, “transmitting information to the brain at a very fast pace.”

Bohórquez next wanted to show that the neural circuit plays a role in behavior. His lab created a behavioral assay in which mice were given access to sugar and an artificial sweetener. Using a specialized optic cable designed by Anikeeva, Bohórquez and Anikeeva’s labs collaborated to develop a new tool for the use of optogenetics in the gut of living mice, he says. The study, published in 2022, showed that sugar intake triggers glutamatergic signaling, and artificial sweetener triggers purinergic signaling using ATP as a neurotransmitter.

Over time, the mice preferred sugar over artificial sweetener, but once the researchers used optogenetics to inhibit neuropod cells, that preference went away. In other words, neuropod cells “not only detect the glucose, but then, by releasing glutamate, they guide the animal towards the sugar rather than the sucralose,” Bohórquez says. This work linked neuropods to behavior, he adds.

T

he idea that “a cell in the gut will guide your [food] choices” was unprecedented, he says. And in fact, some in the field have not been convinced. Laurent Gautron, assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, says the concept of fast synaptic transmission from the gut to the brain “remains unproven.”In their own study, Gautron and his colleagues found that vagal neuron axons made contact with less than 0.5 percent of enteroendocrine cells. (Another group found no evidence of direct contact between the cells.) Also, at the molecular level, these cells did not express markers indicative of synaptic activity, Gautron says, suggesting there is little evidence of synaptic transmission from enteroendocrine cells.

Bohórquez notes that factors such as the specific cellular marker used, the age of the animal and the region of the gut examined can yield varying data regarding contact between enteroendocrine cells and vagal neurons. But his lab used several methods to be the first to provide “definitive evidence of these connections,” he says.

There is also skepticism around the mechanism of glutamatergic signaling described in Bohórquez’s papers. A group in 2022 showed that no cell type within the intestinal lining, including enteroendocrine cells, expressed glutamate, and the next year another group also demonstrated no evidence of glutamate expression from enteroendocrine cells. It seems unlikely that the gut-brain circuit would often need to communicate synaptically, says Hans-Rudolf Berthoud, professor of neurobiology and nutrition at Louisiana State University. Instead, he says the “main mode” of communication between stomach and brain “is paracrine.” (That concept has been around for decades.)

Bohórquez insists that neuropods enable fast synaptic transmission from the gut to the brain, and he points out that in both studies the researchers used RNA sequencing to determine gene expression. If transcripts for glutamate are present at low levels, their signal can be “comparatively weak” and hard to detect, he says. Also, difficulty in detection is particularly applicable to enteroendocrine cells because they have large amounts of peptide hormone transcripts that might “obscure” glutamate’s expression, he explains.

Still, the questions that Gautron and others have raised don’t necessarily “destroy the argument” for neuropods, Browning says. The data in Bohórquez’s papers have been “incontrovertible,” she says, and “it has the potential to be a big idea.”

Even his detractors have not fully written off the neuropod concept. “Is there enough proof of it or not?” Berthoud says. “In this case, I think it’s going to show in 5, 10 years.”

T

he Bohórquez Lab has published just three research articles in 10 years. That isn’t a lot of volume, but having “several key papers” already sets Bohórquez “apart from many others in our field,” says Semir Beyaz, assistant professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. And Naama Reicher, a postdoctoral associate in Bohórquez’s lab, considers the lab to be “high attention.” The lab has published in high-impact journals, and Bohórquez also has spoken about his work in outlets with mainstream appeal—a TED Fellows conference presentation in 2017, the popular Huberman podcast in 2024.Maya Kaelberer, assistant professor of physiology at the University of Arizona and a former postdoctoral fellow in the Bohórquez Lab, says it’s understandable the lab has received “pushback” because of the long history of research into hormonal signaling. “Your life’s work is on one thing,” such as paracrine signaling, she says, “and then we come out and we say, ‘Well, there’s a synapse,’” as well.

Bohórquez is not fazed by “respectful” critiques of his work. That is part of being a scientist, he says, and he understands questions will follow new ways of thinking. This is how science progresses, he says, as hard as big ideas can be to prove. He points to the birth of optogenetics as an example. Karl Deisseroth, professor of bioengineering, psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University, discovered in 2005 that a light-activated ion channel can control action potential firing in the mammalian brain. His paper has gone on to be cited more than 6,000 times, and optogenetics has become one of the most useful tools in research, winning Deisseroth the BRAIN Prize, the Breakthrough Prize and the Massry Prize, among others. Yet the concept alone, before its invention, would have befuddled most researchers.

“If I would have told you 20 years ago that I could make a mouse eat with light,” says Bohórquez, “you would have been, ‘Get out of here.’”

Bohórquez also wants to work on big ideas. The three papers his lab has published are just “fractions” of what he ultimately hopes to discover about the gut and behavior, he says. And it is partly this pursuit of big ideas that sets Bohórquez apart, Browning says: his ability to ask questions that seem “improbable,” with theories that “other people might consider mad.”

Explore more from The Transmitter

Novel neurons upend ‘yin-yang’ model of hunger, satiety in brain