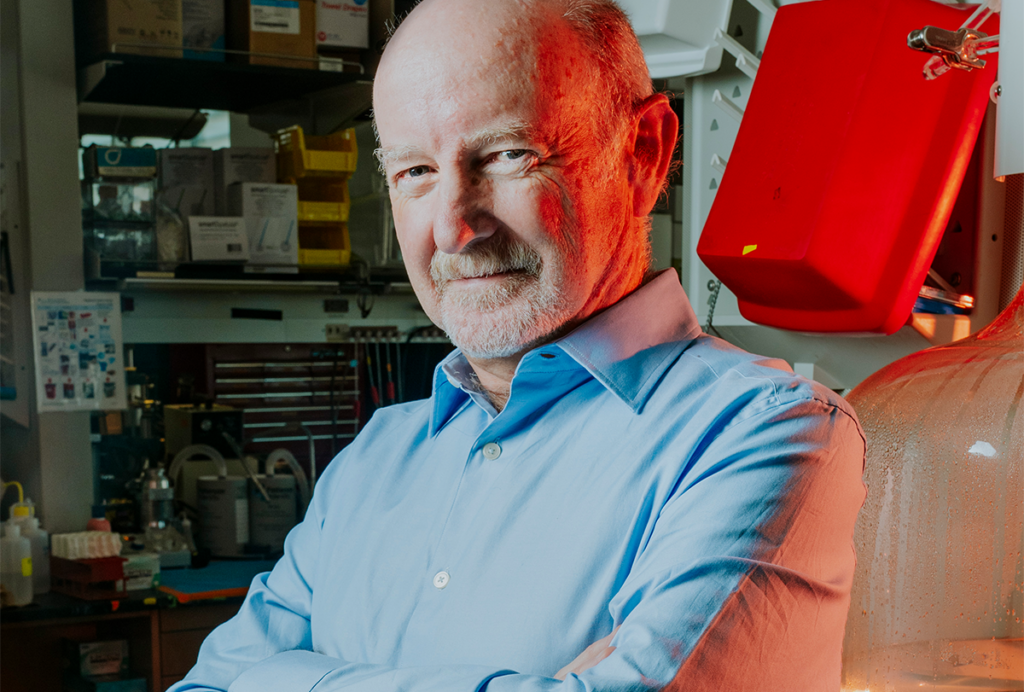

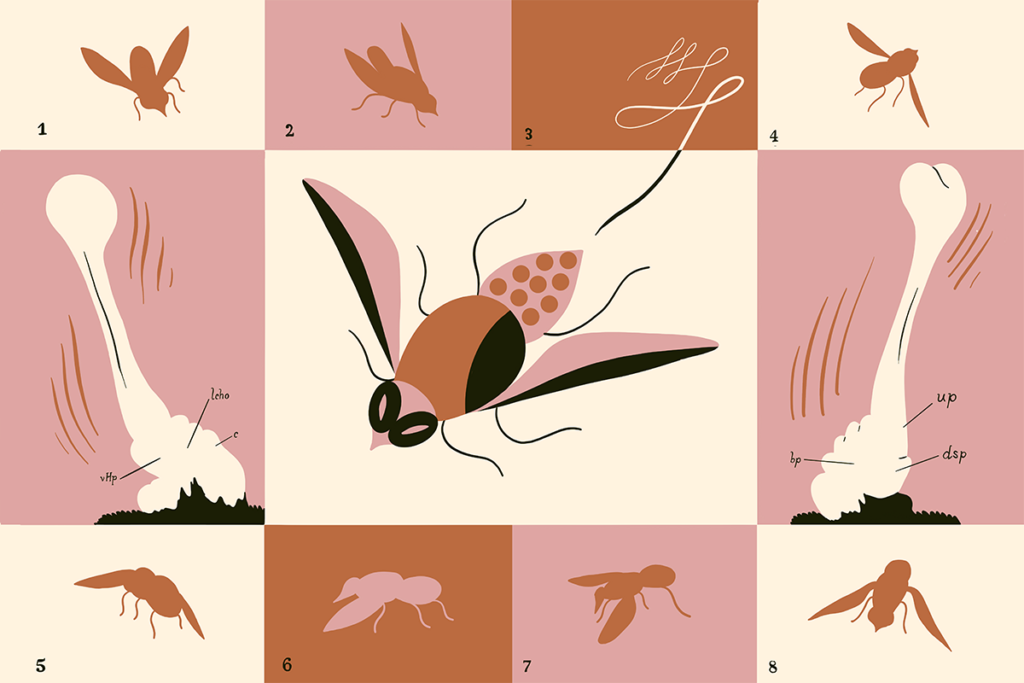

In the 1980s, A. James Hudspeth and Jonathon Howard, then a postdoctoral researcher in Hudspeth’s lab at the University of California, San Francisco, were trying to tease apart how hair cells in the ear convert mechanical sound waves into electrical signals. The pair theorized that molecular springs physically pull open ion channels in the cells, and wanted to measure the stiffness of the long fibers protruding from the cells.

But that kind of experiment requires absolute stillness, and Hudspeth’s lab was located on the eighth floor of an earthquake-proof building. Every door slam reverberated throughout the building and “killed the measurements that I was trying to make,” recalls Howard, now a professor of physics at Yale University.

So Hudspeth went underground. He found an abandoned swimming pool in the basement and built an electrophysiology rig in the deep end. “It worked absolutely brilliantly,” Howard says. The data they collected on their first day supported their spring theory, later outlined in a 1988 Neuron paper. “We were just absolutely single-mindedly going after it,” Howard says.

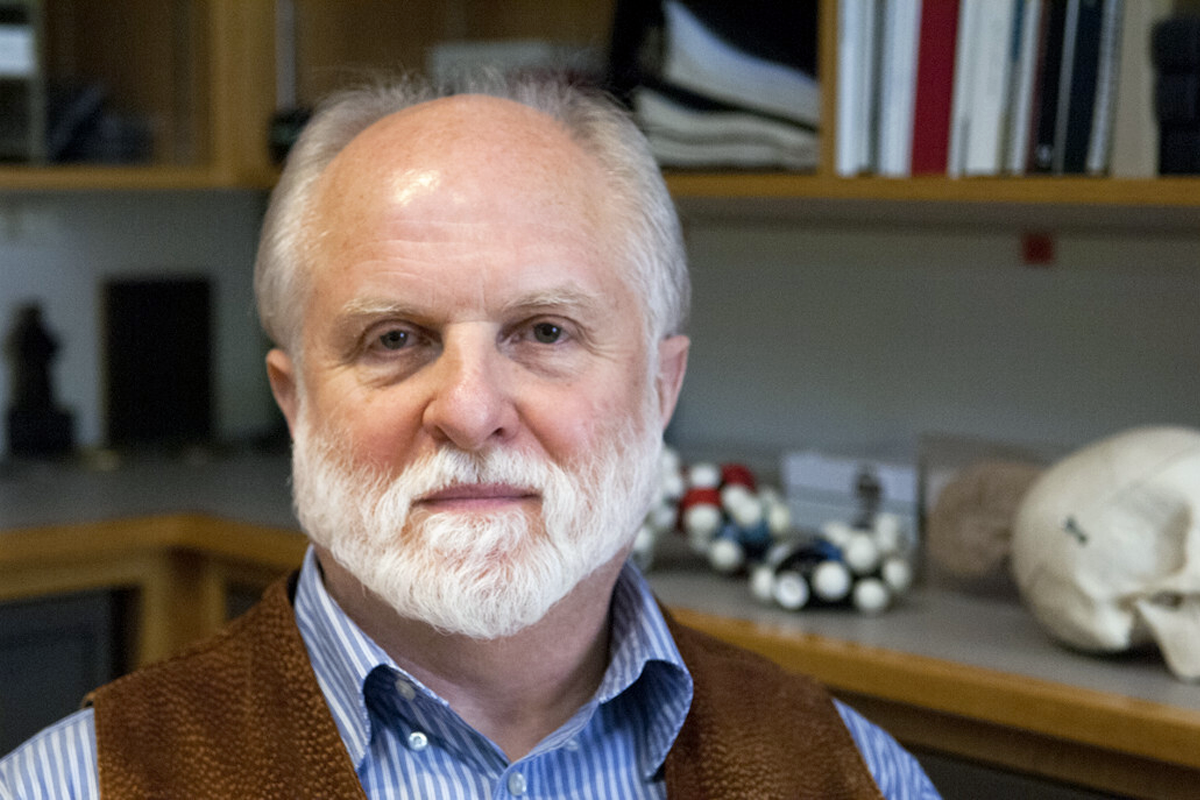

Hudspeth, who died 16 August at age 79 and is survived by his wife Maurine and two children, remained rigorous and single-minded through his 50-year career studying hair cells. “He had little patience for compromising with a problem,” says Marcelo Magnasco, professor and head of the Laboratory of Integrative Neuroscience at the Rockefeller University. “He just went out and solved the problem.”

H

udspeth was born in Texas on 9 November 1945. He grew up near a bayou outside Houston, collecting critters with his younger brother and eventually amassing “a menagerie” of more than 200 animals, as he later wrote, including armadillos, tarantulas, racoons, salamanders and a breeding colony of around 100 box turtles.In the 1960s, he attended Harvard and earned his bachelors, masters, Ph.D. and M.D. degrees. For his graduate studies, Hudspeth approached the future Nobel-prize-winning duo of David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel and asked to join their lab. Right away, the pair realized that Hudspeth was an “extraordinary” student, recalls the now 101-year-old Wiesel. “He’s one of the brightest individuals I’ve met in my life.”

He was also an “independent character,” Wiesel says, and rather than study vision like his mentors, Hudspeth became fascinated with hearing. Hudspeth came across the subject when a few professors “wanted to get out of some work,” and asked him to lecture on hearing and balance, he said in a 2020 interview. He was hooked.

He completed a brief postdoctoral fellowship with Åke Flock at the Karolinska Institutet studying hair cells, the epithelial cells in the cochlea named for their hair-like protrusions jutting out of the cell body, before beginning his own lab at the California Institute of Technology in 1975.

At this point, the field knew that hair cells served as the receptors for the sense of hearing, and some details of their structures were known, but nobody understood the cells’ transduction mechanism, says Robert Fettiplace, professor of neuroscience at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

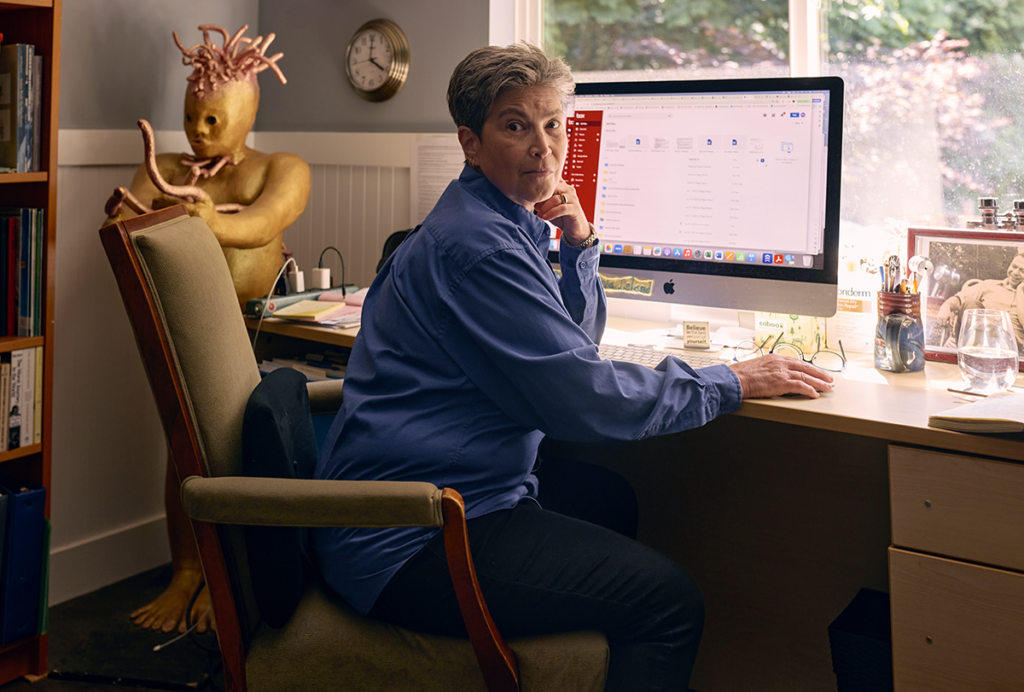

Part of the problem lay with studying a structure as delicate as the cochlea. Particularly in mammals, removing the cochlea damaged it and ruined its physiology. Researchers were “awestruck by its awesome mechanosensitivity,” says Ruth Anne Eatock, professor of neurobiology at the University of Chicago and a former graduate student in Hudspeth’s lab. “They were just terrified of doing anything directly with it.”

So Hudspeth found a better model: the bullfrog sacculus. After a simple, 15- to 20-minute dissection, “you’d have this field of thousands of hair cells to choose from,” Eatock says.

Hudspeth and David Corey, his first graduate student, poked the cells’ hair bundles with a glass rod and measured the resulting electrical activity—the first look at the mechanism of hearing transduction.

H

udspeth’s career took him to the University of California, San Francisco, and then the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center before he landed at the Rockefeller University in 1995. At each place, he dove deeper into how hair cells work, including the spring-gating mechanism project with Howard, as well as how hair cells amplify signals, why they are so sensitive to different sound frequencies and how they transmit messages to neurons. In the latter part of his career, he studied hair cell regeneration and developed an ex vivo preparation of the gerbil cochlea. “He looked at every interesting thing that a hair cell does,” Eatock says. “There wasn’t a thing that he left untouched.”Although he focused on only one topic during his research career, he had an “unquenchable intellectual curiosity” for almost all domains of knowledge, Magnasco says. He read widely and loved to discuss poetry, world politics, music and art. He was a “species fiend,” Magnasco says, who could tell you the different shapes of “some bone in bird A and bird B,” and he used many animals in his work, including zebrafish, alligators, geckos, chickens and gerbils.

Once, Hudspeth ordered “some weird microscopic animal,” perhaps a tardigrade, Magnasco says, simply because he was curious about it. He wanted to examine it under the microscope without squashing it under a cover slip, so he started breaking pieces of glass with his bare hands and assembled a makeshift corral to house the animal in water. He did it as casually as tying his shoes, Magnasco says. “I mean, who does that?”

His curiosity extended to what he could learn from his students, says Pascal Martin, team leader at the Institut Curie and former postdoctoral researcher in the lab. Hudspeth made his students feel like “you had some importance, because you had something to bring,” even if you weren’t aware of it, Martin says. But he also had high expectations and “didn’t suffer fools,” causing friction with some trainees, says Peter Barr-Gillespie, professor of otolaryngology at Oregon Health & Science University and former postdoctoral research in Hudspeth’s lab.

Hudspeth was a gifted science communicator and teacher. He was fond of making props to aid his explanations, including a decommissioned mousetrap to demonstrate how springs open and close the hair cells’ ion channels and a giant model of hair bundles made with PVC pipe. Barr-Gillespie recalls spotting Hudspeth sitting on a bench for hours, practicing a talk, and Eatock says he held full dress rehearsals for his introductory biology lectures.

Hudspeth earned the 2018 Kavli Prize in Neuroscience, which he shared with Fettiplace and Christine Petit, and was elected to the National Academy of Sciences, but his work was still underrecognized, Martin says. Wiesel says he nominated Hudspeth for the Nobel prize many times, to no avail.

Even after receiving a glioblastoma cancer diagnosis, Hudspeth kept working on experiments until June, Martin says. As his health declined, Hudspeth suggested that his friends, colleagues and former trainees gather in Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, to vacation and give scientific talks, as either an early 80th birthday celebration or a memorial.

It turned out to be neither: Shortly before the mid-August trip, Hudspeth became too ill to travel. The gathering took place anyway, with Hudspeth attending via Zoom.

“We did not throw up our hands and say, ‘Well, we don’t need to do these talks anymore’,” Barr-Gillespie says. “That’s not the attitude that he instilled in people.”