Clinical research: Metabolic disorders rare in autism

Screening for metabolic disorders in children with autism is not cost-effective, according to a study published 7 July in PLoS One. The researchers argue instead for careful individual clinical analysis.

Screening for metabolic disorders in children with autism is not cost-effective, according to a study published 7 July in PLoS One1. The researchers argue instead for careful individual clinical analysis.

Some rare metabolic disorders, such as phenylketonuria — caused by intolerance to the amino acid phenylalanine — lead to many of the same symptoms as those seen in autism. Many of these disorders are treatable, and can lead to severe consequences if undiagnosed. Because of this, psychiatry clinics routinely screen individuals with autism for metabolic disorders.

However, only 2 of 274 children with autism treated at a clinic in Paris, France between 2006 and 2007 tested positive for a metabolic disorder, the new study found.

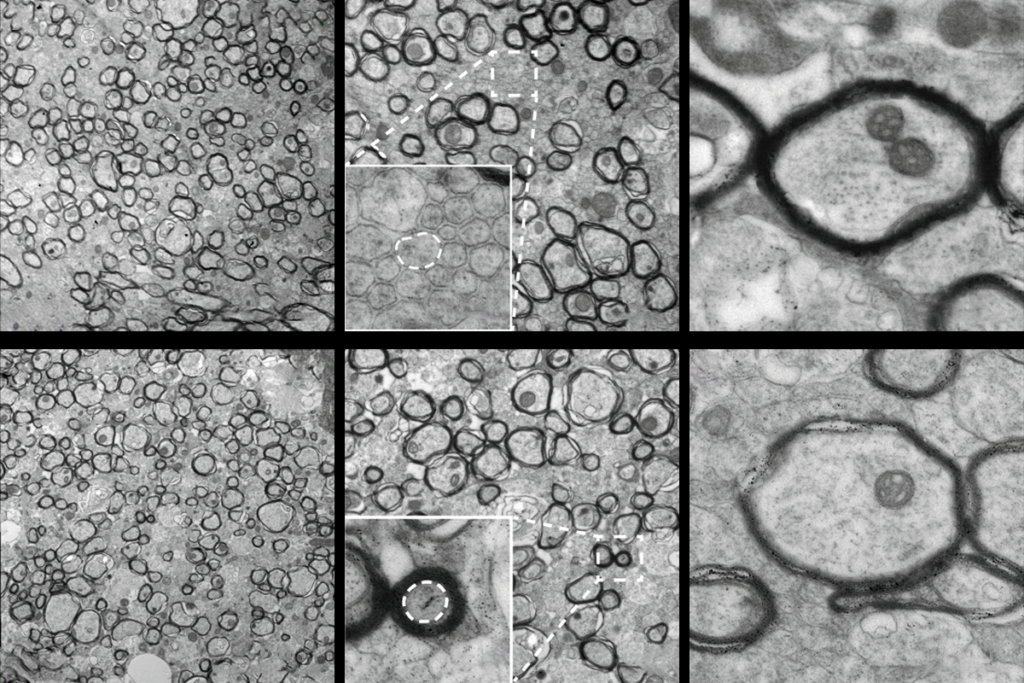

One child has 3-methylglutaconic aciduria, a disorder affecting mitochondria, the energy center of the cell. The other has elevated levels of creatine in the urine, which is an indicator of kidney dysfunction.

Studies have associated both mitochondrial disorders and elevated peptide levels in urine with autism.

Because 0.5 percent of the general population also has a metabolic disorder, children with autism are not a particularly high-risk group, the researchers suggest. The study does not mention whether treatment for their metabolic disorder alleviated autism symptoms in the two children identified in the study.

References:

-

Schiff M. et al. PLoS One 6, e21932 (2011) PubMed

Recommended reading

Sex bias in autism drops as age at diagnosis rises

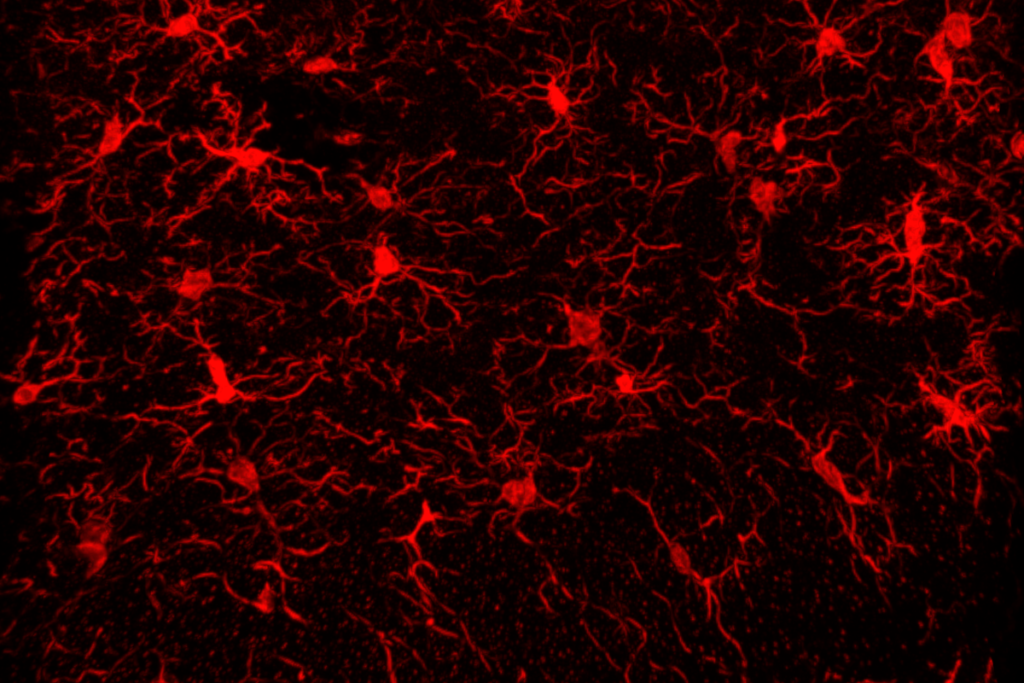

Microglia implicated in infantile amnesia

Explore more from The Transmitter

This paper changed my life: Ishmail Abdus-Saboor on balancing the study of pain and pleasure