The Seeds of the Dual Stream Model of Speech Processing

I met David Poeppel during my stint as a postdoctoral fellow in Steven Pinker’s lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) between 1991 and 1993.

David and I were both funded by the new McDonnell-Pew Center for Cognitive Neuroscience, me as a postdoc and David as a graduate student. The prospects for the field at that time were dynamic and exciting. The first positron emission tomography (PET) studies of language and other cognitive abilities were emerging, and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which offered the hope of a completely noninvasive and widely available method for measuring neural activity with high spatial resolution, had just been invented. At the same time, magnetoencephalography (MEG) was also being developed, which held promise for high-temporal-resolution measurements of auditory and speech processes. It was a good time to be in one of the world’s first cognitive neuroscience programs.

David was working on the neural basis of phonological processing and had taken a long, hard look at the PET studies discussed in Chapter 4, along with a couple more that involved written stimuli. He basically called bullshit on their localizations of phonological processes, which, he noted, didn’t converge with each other due to task design issues. This gained him substantial attention—which sometimes included the glare of disdain—from the senior guard of the field.

He had his own theory about the neural basis of speech perception, which I learned about when he gave a talk at the “McPew Center,” as we called it. Arguing primarily from the bilateral distribution of pure word deafness and the bilateral distribution of speech activation in functional imaging, Poeppel claimed that speech perception was bilaterally mediated. He was just starting out on his career, but I was a seasoned scientist—or so I thought, having commenced my graduate training way back in 1988 (it was about 1991)—and was well schooled in hemispheric asymmetries, aphasia and the Geschwind model. In fact, I had just finished my Ph.D. under Edgar Zurif, a big shot at the Boston V.A. Aphasia Research Center, which was founded by Norman Geschwind. I had attended grand rounds regularly and hobnobbed with the likes of Harold Goodglass, Margaret Naeser, Sheila Blumstein and other prominent figures in aphasia research. (Well, I saw them in the halls now and then.) After his talk, I informed David that, while the idea was interesting, the evidence that he presented for it was not strong. Geschwind, I explained, had a theory about why bilateral lesions can cause word deafness; and, by the way, you can get word deafness from unilateral lesions too. There was also evidence, I continued, from dichotic listening and lesion data that the right hemisphere is specialized for tonal, prosodic or emotional aspects of speech. Finally, I concluded my mini-lecture by explaining that you get aphasia from left—but not right—hemisphere damage in the typical case. Yes, I was one of those people who was fully hypnotized by hemispheric dichotomies.

I can’t remember his counterarguments. Perhaps I was unimpressed or just too dichotomy drunk to take them seriously. We did our own separate thing for the rest of our overlap at MIT, interacting now and then I suppose (I honestly don’t remember) until I left to work on hemispheric lateralization of sign language with Ursula Bellugi and Ed Klima at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California.

The critical issue circulating around sign language aphasia, my new research topic, was its lateralization pattern. Was it left hemisphere organized because it is a language? Or right hemisphere organized because it has a strong visuospatial component (then thought to be a right-hemisphere function)? I realized that we could home in on more specific and trendy ideas, such as Paula Tallal’s fast temporal processing theory of left-hemisphere specialization for language. Spoken language contains such fast temporal signals, but signed language is much slower and more spatial. Therefore, Tallal’s model predicted that signed language should not be strongly left dominant. It turns out, however, that the hemispheric asymmetry of signed language is pretty much identical to that of spoken language, as revealed by our sign aphasia work, thus disproving fast temporal processing as the basis of left dominance for language.

Our conclusion was questioned, though, when the first fMRI studies were carried out on signed language, comparing the perception/comprehension of American Sign Language (ASL) with the perception/comprehension of written English. Reading English yielded mostly left-dominant activation, whereas viewing ASL produced a more bilateral pattern. This pushed me to look more closely at the activation patterns of spoken language (a more natural comparison to ASL), which was largely bilateral, as we’ve seen in the previous chapters. And this led me to consider the possibility that language lateralization was not all or nothing; rather, it varied across tasks. We concluded that the right hemisphere is indeed involved in receptive sign language processing, but so is it for spoken language, and to a similar degree. Exactly what it was doing, though, was unclear.

Thus, my interest was piqued in the possible involvement of the right hemisphere in aspects of receptive language, both signed and spoken, and David and I started talking at conferences and by phone and email about ways to further test the dominant theories. We toyed with a few ideas but never really hit on a critical test. In the meantime, while preparing a lecture on the neuroanatomy of speech perception for my undergraduate “Language and the Brain” course, I came across a surprising piece of evidence.

This was around 1997, so I was well aware of the essentially bilateral, symmetric activation in the superior temporal lobe during speech listening. The mainstream interpretation of these results at the time, as detailed in the previous chapter, was that left-hemisphere activation reflected low-level auditory plus linguistic-phonological processes, whereas right-hemisphere activation reflected low-level auditory plus some other higher-level nonlinguistic process, such as emotional prosody. This seemed to be broadly (if indirectly) supported by lesion data—aphasia is typically caused by left-, not right-hemisphere damage—but I wanted to show my students more specific evidence for this claim.

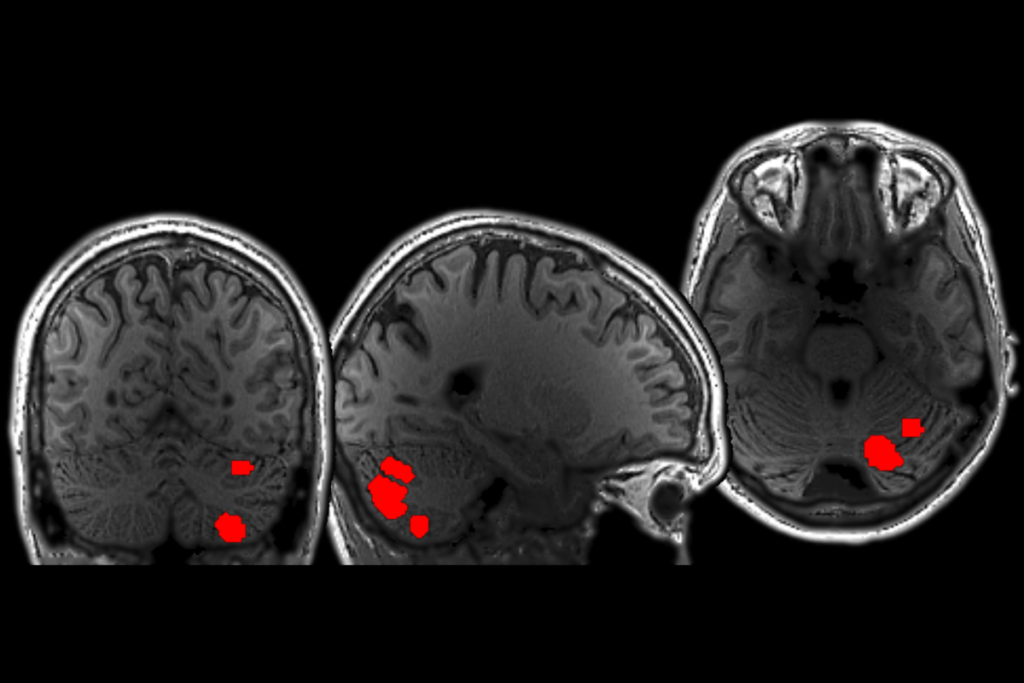

The most straightforward test would be to examine the effects of lesions to the left-versus-right-hemisphere regions that activated during speech listening in functional imaging studies. In the era of functional neuroimaging, I had an advantage over previous theorists interested in this question because I knew exactly which areas of the brain activated to speech, the superior temporal lobe, and could focus my attention on the effects of lesions in that zone. In the past, researchers like Geschwind couldn’t be sure whether the critical zone was just the superior or middle temporal gyrus, whether it was the anterior, middle or posterior parts, or the angular gyrus or supramarginal gyrus, or some combination of these. Because I knew where to look, I could take a different tack. I consulted the literature and tried to find cases of patients with damage to the left STG. If that was the critical zone for speech perception, as the dominant interpretation of the functional imaging data suggested, then I should find examples where damage in that area caused at least moderate receptive phonological deficits, if not full-blown word deafness.

I succeeded in finding cases with damage in the critical left STG zone, but they had no trace of receptive speech problems. Instead, affected individuals had speech production problems, conduction aphasia in particular. I dug deeper, probing the literature for evidence that more extensive damage in the left temporal lobe might cause receptive phonological problems. This led me to the work described in Chapter 3, showing that even patients with substantial receptive language problems (such as Wernicke’s aphasia) don’t have predominantly phonological receptive speech perception deficits. Finally freed from my hemispheric dichotomy goggles, I called David and told him that I had found some evidence that really clinched his case for bilateral speech perception. We decided that we should write a simple, short paper in which we lay out the evidence and then move on to more interesting things.

But it turned out not to be so simple.

Excerpted from Wired for Words: The Neural Architecture of Language by Gregory Hickok. Reprinted with permission from the MIT Press. Copyright 2025.