Knowledge gaps in cephalopod care could stall welfare standards

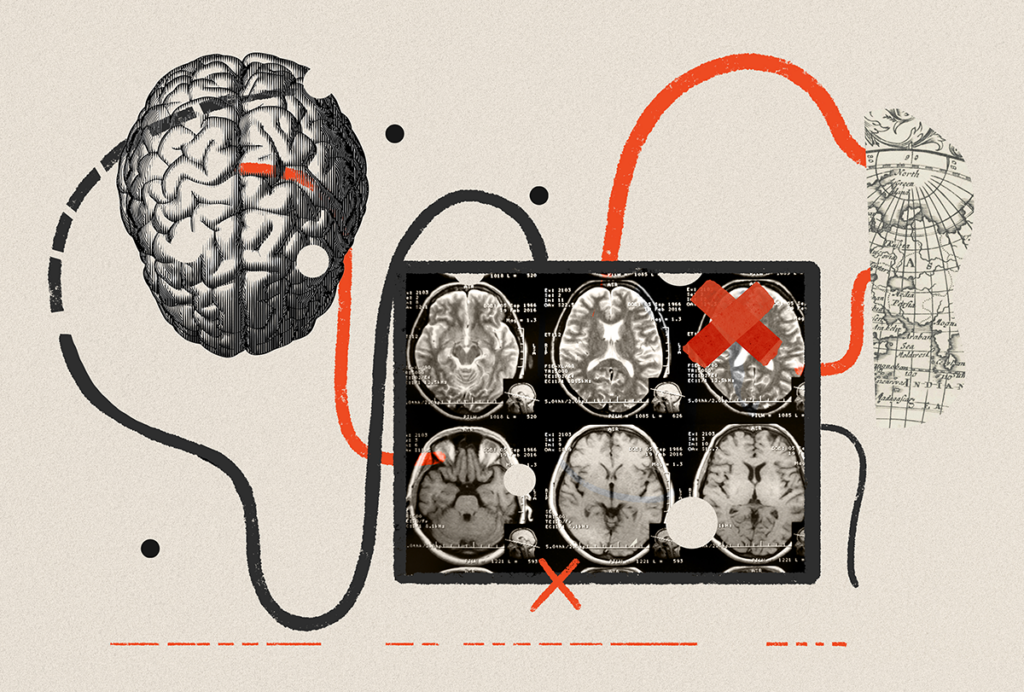

The U.S. National Institutes of Health wants to regulate research involving cephalopods. But there aren’t enough rigorous studies to base the regulations on, veteran cephalopod researchers say.

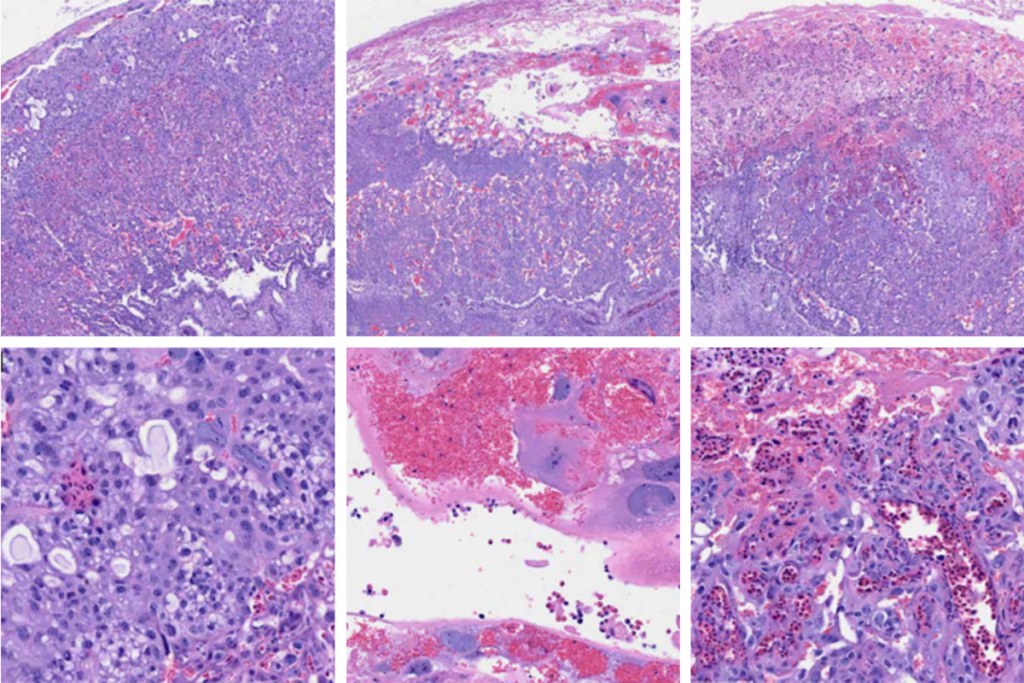

A growing number of neuroscientists are stepping away from traditional model organisms into the squishy world of octopuses, squid, cuttlefish and other cephalopods. These intriguing invertebrates offer a rare window into the neural basis of unusual behaviors—including camouflage, eight-arm motor control and deep-sea vision—and the evolution of complex nervous systems radically different from our own.

The U.S. government is paying attention to cephalopods, too: Last September, in response to increasing evidence that cephalopods can feel pain, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) proposed extending research animal protections to cephalopods—a move that many other nations have already taken.

Under the proposed guidelines, an institutional animal care and use committee, or IACUC, must approve in advance any NIH-funded experiment performed on cephalopods. Studies in no other invertebrate animal model, such as Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster, must meet this requirement. The NIH published the draft guidance on 7 September and accepted comments from the public until 22 December.

Several veteran cephalopod researchers, including Robyn Crook, associate professor of biology at San Francisco State University, told The Transmitter that they are largely on board with the proposal but have concerns. They say that there aren’t enough rigorous studies on basic cephalopod biology and care for researchers and IACUCs to use when designing and evaluating protocols. They also say they worry that this change could lead to more restrictive regulations that do not consider the cornucopia of cephalopod species, or how they differ from vertebrates.

“In many aspects, we’re putting a square peg in a round hole,” says Trevor Wardill, assistant professor of ecology, evolution and behavior at the University of Minnesota. “It’s not that I’m against it. It’s just I think we need to be really careful” about adapting broader vertebrate regulations so they are suitable for an invertebrate, he says—“especially an invertebrate that we know very little about.”

The NIH’s request for comment acknowledged this lack of insight and stated that grandfathering cephalopods into the vertebrate policies would be “problematic.” The agency also underscored the need for additional “scientific study and validation” of cephalopod-specific best practices for care.

Cephalopod husbandry does not have a robust literature for multiple reasons, Crook, Wardill and others told The Transmitter. These studies lack funding, scientific journals lack interest, and researchers have had a tendency to share techniques in more informal ways. But now that more scientists are eager to start working with cephalopods, this dynamic needs to change, Crook says.

“Someone needs to support these studies if they’re going to claim that cephalopod welfare is this important,” Crook says.

D

uring IACUC proceedings for other animal models, researchers must outline how they plan to use animals in an experiment, including, for example, how many animals will be used and why; details of any surgical procedure or training paradigm; anesthesia methods, analgesic dosages and schedules; and humane endpoints for euthanasia, in case pain-relief procedures aren’t enough. The IACUC must approve the protocol before the study can begin, and it can stop a study if researchers stray from that protocol.Many of these procedures for mice and rats are outlined in regulatory documents, such as the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.” Even for brand-new techniques, the standard practices for analgesia and pain monitoring can still apply.

If the NIH guidelines are approved, however, cephalopod researchers—and their IACUC assessors—will be left in a “legal and ethical gray area,” Crook says.

The most pressing gap in the literature, several researchers say, is the proper type, dosage and schedule for analgesics. “We have no idea what that would be in a cephalopod,” says Clifton Ragsdale, professor of neurobiology at the University of Chicago. So far, he says, only one study—from Crook’s lab—has compared the effectiveness of different painkillers in cephalopods, and it looked at just one species: the hummingbird bobtail squid.

There is also no way to objectively assess the behavioral state of a cephalopod or quantify how relaxed or stressed it is, Crook says. Rodent researchers can do this by tracking changes in facial expression through grimace scales.

That lack isn’t a problem for experienced researchers, Wardill says, because cephalopods “tell you immediately if something’s wrong”: They change color, hide, ink or otherwise alter their behavior. But there’s not a standardized way to share or teach this knowledge as more neuroscientists join the field, Crook says.

“You can’t carry a 15-year-experienced cephalopod researcher around and plunk them in every room and say, ‘Tell us about this one.’ You need some kind of validated assessment metric that would let you evaluate that in an objective way,” Crook says. This type of metric could also be used to quantify whether pain-reduction measures submitted to an IACUC actually work, she says.

Other knowledge gaps include standards of care for cephalopods, such as minimum tank sizes, proper diet, surgical techniques, post-operative care and the ideal water chemistry balance. “If the animals are all upset about the water quality, then they’re not going to behave normally,” Wardill says. “And so whatever I’m going to publish won’t be sensible.” And every species could have different needs.

“I’m sure from a legislative point of view it’s easy to just group them in as cephalopods,” says Connor Gibbons, cephalopod facility manager in Richard Axel’s lab at Columbia University, “but there’s dozens and dozens of species, separated by millions of years of evolution, that need their own special standards to be set for them.”

C

ephalopod researchers in the U.S. are not left with nothing to go on, however.The NIH’s move follows cephalopod protections that have cropped up over the past decade in other regions, including the European Union, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

In 2015, an international group of scientists compiled one of the most comprehensive care guides, following the European Union’s policy change. That guide summarizes the evidence for how best to care for common species, such as the California two-spot octopus and the common cuttlefish, with suggestions for housing, diet, enrichment activities, anesthesia and euthanasia.

But because of the sparse-literature problem, it cites personal communications or unpublished data more than 30 times, and often makes suggestions based on data from a single study, says Gregory Barord, a marine biologist and instructor at Des Moines Public Schools who studies nautiluses, the only living shelled cephalopods.

“Personal communications are valid, and unpublished data is valid, but where’s the real source of that?” Barord says. “And if that person disappears from the field, or dies, what do you do with that?”

The guide acknowledges that “the evidence base for some aspects of these guidelines is not strong.” And they still “are so much better than nothing. But we could do more,” Crook says. “We could do a lot more with proper control studies that really address welfare as an objective.”

These kinds of studies would need a dedicated funding source, Crook says, which does not currently exist. Another way to support this work would be to relaunch a federally supported cephalopod center, Wardill says, to provide researchers with animals, short-term facilities, and experimental and care guidance. The NIH funded a national cephalopod center from 1976 until 2010, and such centers exist for rodents, primates, zebrafish and other common animal models.

In recent years, the Marine Biological Laboratory, an affiliate of the University of Chicago, has operated a cephalopod breeding program, but it’s not a replacement for a federal facility, Wardill says. “For a community to build and get bigger and understand more about cephalopods, we need more infrastructure.”

W

ithout that infrastructure, many cephalopod enthusiasts gather information from online forums, such as The Octopus News Magazine Online (TONMO). The forum is made up of expert marine biologists and aquarists, including Barord, who is one of the site moderators, as well as hobbyists who have learned about caring for cephalopods “from getting octopuses or whatever species and keeping them alive,” Ragsdale says.Gibbons and other scientists told The Transmitter they used TONMO as a resource when they first started learning about cephalopods but eventually graduated to speaking to other scientists directly as they gained experience.

Barord says he hopes that, despite time and funding limitations, researchers will start publishing their husbandry findings in a more systematic way. “We have to figure out a way to get it down in one place,” he says. “I think there’s probably a better way to do it, but TONMO is the thing trying to do it.”

In this vein, Gibbons is working on a husbandry guide for the dwarf cuttlefish; the Axel Lab already shares the scientific tools they’ve developed for the species.

A broader protocol-sharing project sponsored by the NIH and Federal Demonstration Partnership, an association of federal and academic institutions that aims to make the research process more efficient, is also in the works. The Compliance Unit Standard Procedures (CUSP) project plans to create an online database where researchers can share their IACUC-approved procedures. It is slated to include a variety of procedures—surgeries, behavioral tests, imaging and husbandry—for typical and “unusual” lab animals, including cephalopods, says Michelle Brot, scientific reviewer in the Office of Animal Welfare at the University of Washington and one of the CUSP project organizers. The team says they hope to launch a pilot version of the site in the next few months.

The NIH is reviewing the comments that were submitted on the draft guidance and plans to provide additional information this year, a spokesperson told The Transmitter in an email.

In the meantime, Gibbons, a trained aquarist, says he would like to see more labs hire husbandry professionals from zoos and aquariums to help set up and run their cephalopod facilities.

Crook says she hopes that neuroscientists pivoting from other animal models will slow down to learn more about new species before jumping straight into experiments.

“There’s lots of low-hanging fruit in cephalopods if you’re a person who’s coming in from working your entire life in rat cortex. It’s such an unexplored world, the head of an octopus,” Crook says. “But there’s so much that we don’t know about the welfare of the animals, so caution is so important.”

Recommended reading

NIH scraps policy that classified basic research in people as clinical trials

BRAIN Initiative researchers ‘dream big’ amid shifts in leadership, funding

Explore more from The Transmitter

Dendrites help neuroscientists see the forest for the trees

Two primate centers drop ‘primate’ from their name