NIH scraps policy that classified basic research in people as clinical trials

The policy aimed to increase the transparency of research in humans but created “a bureaucratic nightmare” for basic neuroscientists.

The U.S. National Institutes of Health will no longer require basic research in people to follow clinical trial reporting requirements, according to an announcement from the agency last Thursday. The change applies to grant applications submitted to funding opportunities with a due date of 25 May 2026 or later.

Scrapping the policy is a “phenomenal” change that will “remove a lot of administrative burden and red tape,” says Jan Wessel, professor of psychological and brain sciences at the University of Iowa, who studies inhibitory motor control in people. “We’re going to go back to something that is, I think, more appropriate, which is classifying basic science as basic science.”

The original policy, first proposed in 2014, required researchers who worked with human volunteers to fill out clinical trial documentation in their grant applications, register their studies on ClinicalTrials.gov and report their results on the site within a year of completion.

The rigid reporting structure of ClinicalTrials.gov is ill suited for basic studies, says Jeremy Wolfe, professor of ophthalmology and radiology at Harvard Medical School, who studies visual attention in people. “It was going to be a round peg in a square hole kind of problem.”

The additional documentation for grant applications “definitely made my life harder,” says Nanthia Suthana, professor of neurosurgery, biomedical engineering and neurobiology at Duke University, who studies memory and emotion in people.

Over the past decade, the NIH continually postponed enforcing the rules, but inconsistencies across institutes and program officers sowed confusion and created an additional administrative burden for many neuroscience researchers who work with human participants, Wessel and others say.

“This shift allows scientists to conduct high-quality research without barriers that affect their work. Researchers may still register studies with ClinicalTrials.gov or submit results on a voluntary basis,” an NIH spokesperson told the Transmitter.

T

Funding agencies and scientists have “an ethical obligation to people who participate in clinical trials or human experiments to make the results of those trials or experiments public,” says Michael Lauer, former deputy director for extramural research at the NIH.

But that frequently did not happen. Only 22 percent of studies on ClinicalTrials.gov slated to end in 2009 had reported their results by January 2011, according to a 2012 study published in The BMJ.

The publication of that study caught the attention of Congress. Members of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce sent a letter that same year to Francis Collins, director of the NIH at the time, inquiring if the study’s findings aligned with the NIH’s internal data on clinical trials.

“The agency discovered, to their chagrin, that they couldn’t answer those questions,” says Carrie D. Wolinetz, former director of the Office of Science Policy at the NIH and now senior principal and chair of the Health Bioscience Innovations Practice at the government relations firm Lewis-Burke Associates. This was in part because the agency did not have a clear definition of what constituted a clinical trial, Wolinetz and Lauer say, so it could not generate a list of all the NIH-funded trials currently underway.

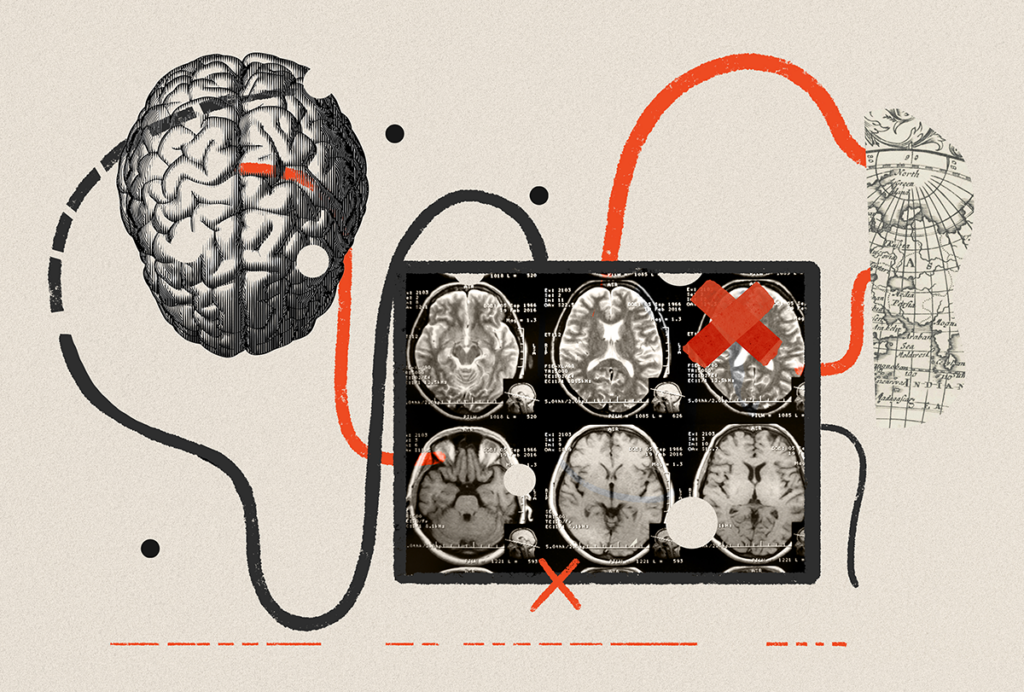

The formal definition the NIH published in 2014 included any “research study in which one or more human subjects are prospectively assigned to one or more interventions (which may include placebo or other control) to evaluate the effects of those interventions on health-related biomedical or behavioral outcomes.” That year, the agency also published the first draft of the clinical trial reporting requirements.

This new definition’s “terminology was either meaningless or completely opaque,” Wessel says. For example, presenting a stimulus to a participant and recording their brain activity could be construed as measuring the outcome of an intervention. “It applied to everything and nothing on a case by case basis.”

O

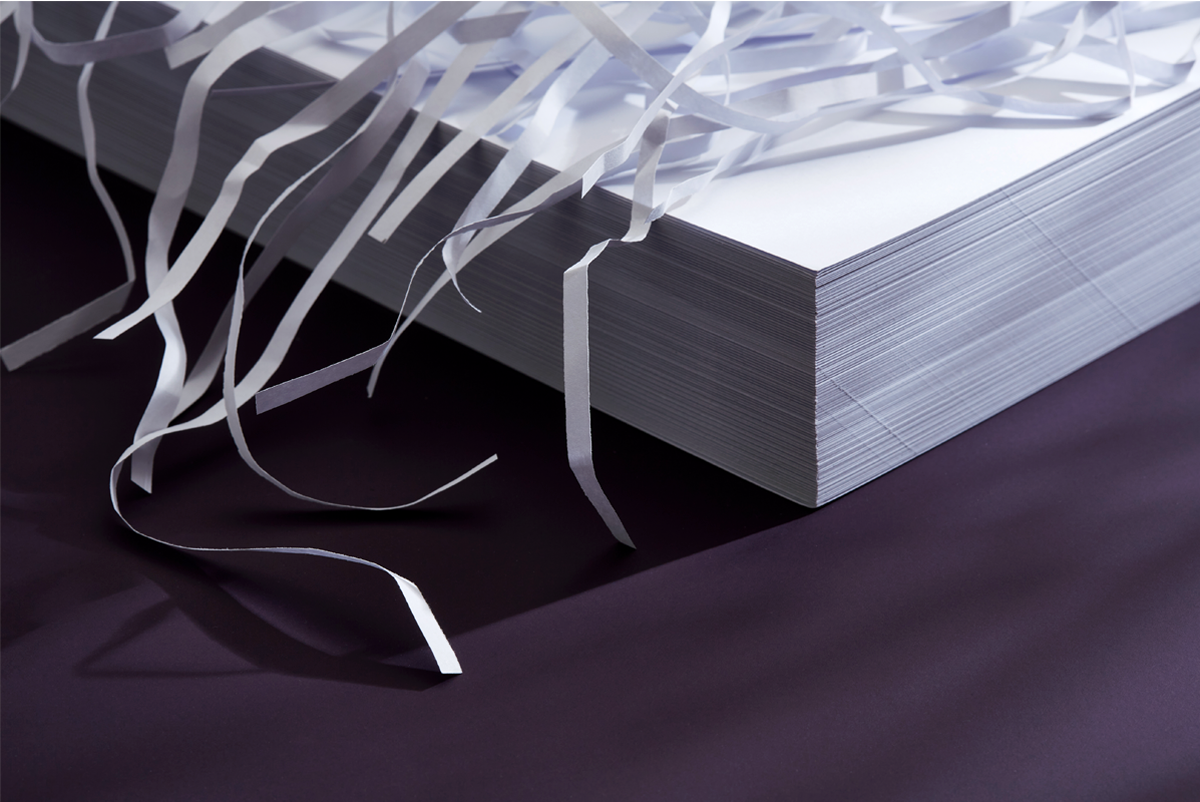

Even though the policy was never officially enforced, differences in compliance among program officers created an extra administrative burden for some cognitive neuroscience researchers.

During her most recent grant submission, Anna Schapiro says her program officer told her she needed to fill out clinical trial documentation for a project on memory reactivation during sleep. “It was a nightmare, truly a nightmare. I almost was unsure whether it was worth the money,” says Schapiro, associate professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Some program officers said any experiment using people qualified as a clinical trial, and others said that was true only for certain manipulations, says Alison Preston, professor of psychology at the University of Texas at Austin, who studies memory in people. This made it unclear if a particular research project could be submitted to a funding opportunity for basic research only or one that allowed clinical trials. So Preston decided to switch all of her grant applications “to clinical trials wholesale,” she says, to avoid having her applications pulled from review, which had happened to some of her colleagues.

This inconsistency also made it harder to serve as a scientific reviewer for grants, Wessel says. In the same pool of applications, some researchers would include clinical trial documentation, and others would not, turning some of the six-page research plans into 35-page documents.

Even though these specific reporting requirements are over for basic research in people, the principle of making research plans and results public and accessible is “a good one that we should all continue to work on,” Wolfe says. “We just need to find a format that is not a bureaucratic nightmare.”

Recommended reading

BRAIN Initiative researchers ‘dream big’ amid shifts in leadership, funding

Without monkeys, neuroscience has no future

What U.S. science stands to lose without international graduate students and postdoctoral researchers

Explore more from The Transmitter

The Transmitter’s top news articles of 2025

Establishing a baseline: Trends in NIH neuroscience funding from 2008 to 2024