Journal retracts two papers evaluating ADHD interventions

Frontiers in Public Health retracted one paper for its “unacceptable level of similarity” to another paper, and the other over concerns about its “scientific validity.”

Two papers touting interventions to enhance brain connectivity in people with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder have been retracted. The move follows reporting by The Transmitter about issues with the papers and two others by Gerry Leisman, research associate at the University of Haifa.

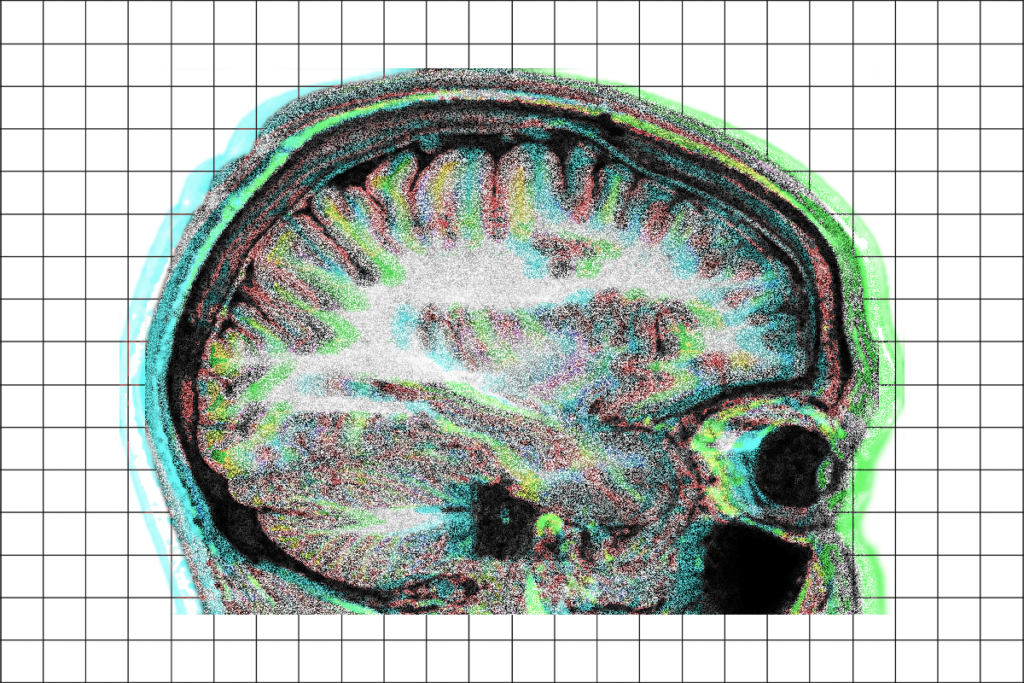

One of the papers, published in Frontiers in Public Health in 2013, found that a 12-week program improved motor and sensory coordination and academic achievement in 122 children with ADHD aged 6 to 12 years. An investigation by the journal found an “unacceptable level of similarity” to a 2010 paper by Leisman that was published in the International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, according to the retraction notice.

The other paper, published in Frontiers in Public Health in 2020, examined how a “hemispheric-based training program” affected the motor and cognitive abilities of more than 2,100 people with ADHD between ages 3 and 22 who received the training at 89 clinics across the United States. The journal investigated the paper because of concerns about its “scientific validity,” according to the retraction notice. “The authors failed to provide a satisfactory explanation and as a result, the conclusions of the article have been deemed unreliable.” A Frontiers spokesperson did not elaborate when The Transmitter asked for more details about the specific issues with the paper.

Leisman did not respond to requests for an interview, but he told The Transmitter in 2023 that the participants in the 2020 study came from a client database for Brain Balance Achievement Centers, a Chicago-based franchise. Brain Balance sells programs that claim to strengthen brain connectivity in children with autism, ADHD and other conditions through “sensory engagement, physical development, academics and nutrition.”

One of the investigators on the 2020 paper, Robert Melillo, is the founder of Brain Balance; Melillo did not respond to The Transmitter’s request for comment. Leisman said in a comment on the post-publication peer review site PubPeer that he does not have a financial relationship with Brain Balance. A representative of Brain Balance told The Transmitter that the company had no involvement with either paper and has not had a relationship with Melillo since 2018.

A 2021 review performed by the nonprofit organization Association for Science in Autism Treatment found that the Brain Balance approach “lacks sufficient empirical evidence and should therefore be considered a pseudoscientific treatment.”

The current program “is based on contemporary developmental neuroscience and supported by a modern evidence base developed independently of any former contributors,” a Brain Balance representative told The Transmitter.

No other articles by Leisman are currently under investigation, a Frontiers spokesperson told The Transmitter in an emailed statement.

S

cience integrity sleuth Dorothy Bishop, emeritus professor of developmental neuropsychology at the University of Oxford, identified issues in several of Leisman’s papers in October 2023 and posted comments on PubPeer. The comments prompted the investigation into the 2020 paper, a Frontiers spokesperson told The Transmitter.Bishop told The Transmitter she does not remember if she contacted Frontiers about the issues she spotted, but she says she most likely did not, because it was not something she typically did at that time. Unless someone else contacted Frontiers, the retractions “suggest they may be being proactive in looking at PubPeer. That’s a really good thing, if true,” Bishop says.

Another researcher suggested that Bishop look into Leisman’s work after attending a conference he organized; the researcher was upset about the poor quality of the scientific presentations and outsized claims about the effectiveness of different interventions, Bishop says. One of the other works Bishop evaluated, a 2018 book chapter describing a clinical trial, claimed that a laser therapy reduced irritability in children and adolescents with autism. The data were “totally unbelievable,” Bishop says.

Bishop outlined several methodological issues with the 2020 paper in her October 2023 PubPeer post, including unclear ethics approvals, vague and irreplicable descriptions of the tested interventions, and the assessors being privy to whether a participant received the intervention or not.

Leisman posted a comment in reply that included “the communication between the authors and each of the reviewers,” he wrote. One reviewer echoed some of Bishop’s concerns: They called the institutional review board process “convoluted” and pointed out that the authors did not describe what their training program entails. “Their introduction discussed a variety of interventions reported but what did they actually do?” the reviewer wrote.

In response, Leisman shared that the paper had been evaluated by six reviewers in 2017 before it was accepted for publication. The Frontiers ethics office informed the team that the work needed to be approved by an institutional review board in the U.S. because it used a U.S.-based database, Leisman wrote; that review determined board approval was not needed because the work did not involve human participants. Frontiers then required the authors to resubmit the paper and undergo a seventh and eighth round of peer review, the comment states.

Five reviewers evaluated the paper, a Frontiers spokesperson clarified in a statement to The Transmitter, which “reflects the collaborative and iterative nature of Frontiers’ peer-review process.”

Leisman did not provide additional information about the interventions performed in the program. “There are many activities that these children perform in the centers,” he wrote in response to the reviewer. “To list all of the activities in detail is too lengthy and we think unnecessary in this venue and none are singularly novel or unique.”

The reviewer replied that “this is a problematic submission and I wish that I had known that this would be the 8th review of a paper before accepting it.”

Recommended reading

Authors retract Science paper on controversial fMRI method

Psychedelics meta-analysis retracted after authors request ‘significant changes’

Explore more from The Transmitter

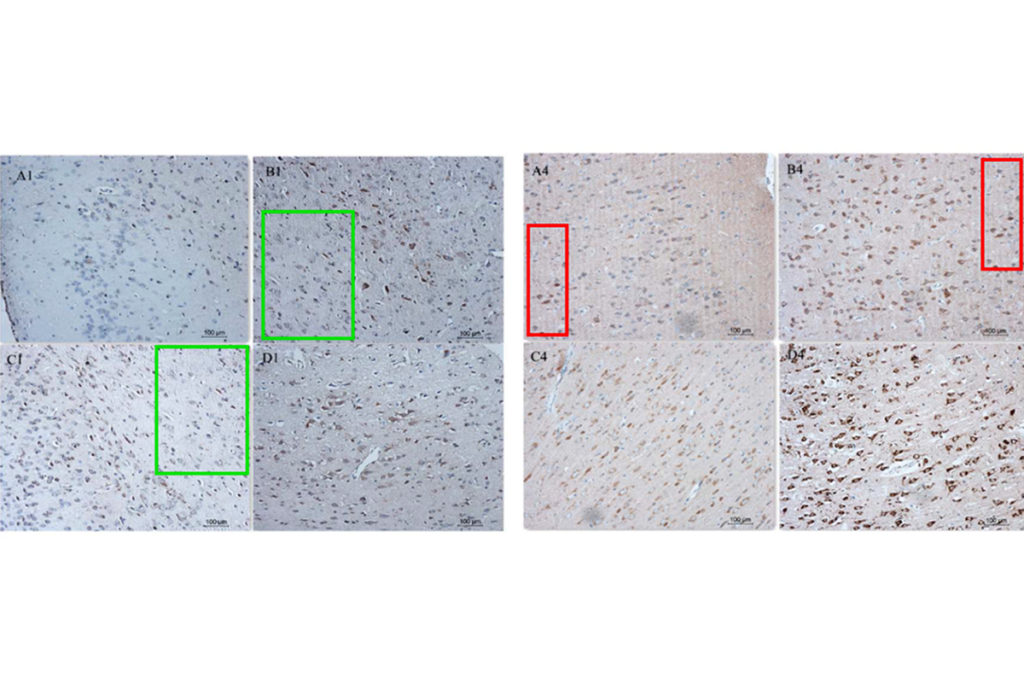

Image integrity issues create new headache for subarachnoid hemorrhage research