Neuropeptides reprogram social roles in leafcutter ants

The mechanisms that control the labor roles of ants may also be conserved in naked mole rats, a new study shows.

Leafcutter ants’ roles can be reprogrammed by manipulating two neuropeptides, according to a new study. These ants are known for their rigorous division of labor in a caste system, with groups performing roles ranging from cutting leaves to nest defense to tending the fungus that is their food source.

Despite physical differences among the ants—the heads of the nest defender ants can be five times the size of the fungal carers’ heads, for instance—it’s still possible to “pharmacologically reprogram them to assume some of the roles that typically other castes assume,” indicating behavioral flexibility, says Daniel Kronauer, professor at Rockefeller University, who was not involved in the work.

The researchers induced the behavioral changes by first using RNA sequencing to uncover target neuropeptides and then manipulating neuropeptide levels in the ants. The study was published in June in Cell.

The work illustrates the close relationship between neuropeptides and behavior, says Shelley Berger, professor of cell and developmental biology at the University of Pennsylvania and principal investigator of the study. Defender ants are “so big and awkward and clumsy,” she says, but after a certain neuropeptide level is lowered, the ant becomes a “nurse tending to the brood.”

The study shows the “importance of neuropeptides as these molecular controllers of incredibly complex” behavioral traits, says Zoe Donaldson, professor of behavioral neuroscience at the University of Colorado Boulder, who was not involved in the study. “I think it’s a really elegant demonstration of just how powerful they are.”

A

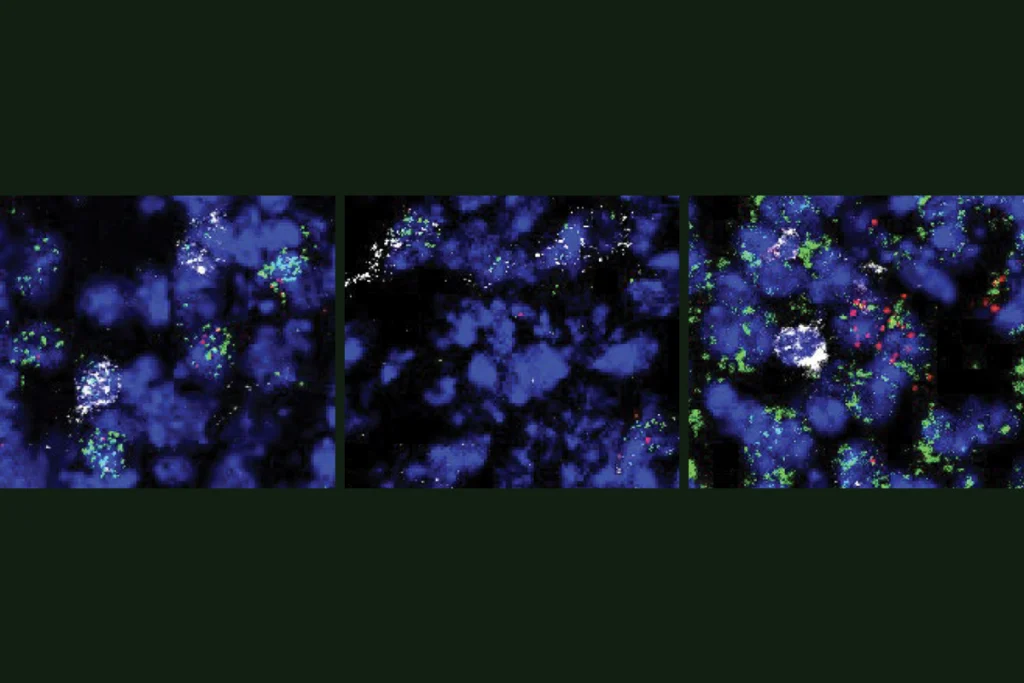

lmost all species of ants live in colonies, but leafcutter ants (Atta cephalotes) have a particularly intricate labor division, says study investigator Karl Glastad, assistant professor of biology at the University of Rochester. He and Berger previously explored hormonal controls of social behavior in Florida carpenter ants, which have two worker subtypes, but leafcutter ants are a “really elaborated version” of that species, Glastad says.In the leafcutter ant study, the researchers first recorded the ants in an experimental arena where they were allowed to interact with leaves, pupae and fungus. Then the team fed the video into the machine-learning tool DeepLabCut to conduct a behavioral analysis and separate the ants into four distinct morphological subcastes of decreasing body size: defensive patrollers, leafcutters, brood carers and fungal gardeners.

The researchers wanted to understand how these behavioral differences are expressed via whole-brain transcriptomics. RNA sequencing showed that each ant subcaste has uniquely expressed genes, demonstrating a correlation between brain gene expression and behavior, they wrote in the study.

Neuropeptides were among the top differentially expressed genes in the four ant subcastes, with the neuropeptide neuroparsin-A (NPA)—known to regulate swarming behavior in desert locusts—being one of the most highly expressed genes for the defensive subcaste, Glastad says. The neuropeptide crustacean cardioactive peptide (CCAP), on the other hand, was highly expressed in the leafcutter subcaste.

The researchers surmised that NPA suppresses an instinct to care for the brood in the defensive subcaste. To test this, they used inhibitory RNA to knock down expression of this neuropeptide. The defensive subcaste ants began to behave more like brood carers, Glastad says, ferrying the brood to the fungal pile in the test arena. When the researchers reversed the experiment, injecting NPA into the carer subcaste, the ants suppressed their brood care significantly.

Altering levels of the neuropeptide CCAP produced similarly clear behavioral swaps. Defensive ants and brood carers, after an injection of CCAP, approached leaves and “did their best to kind of manipulate and try to cut the leaves,” Glastad says, even though they weren’t very good at it. And removing CCAP in leaf harvesters decreased their leaf-moving behavior. The behavioral results were “very clean,” Glastad says.

T

he paper also examined the role of neuropeptides in the naked mole rat, which lives in communities with labor division. Despite naked mole rats and ants being separated by more than 600 million years of evolution, they showed similar gene expression patterns, the researchers found, suggesting conserved neuropeptide roles in eusocial behavior across distantly related species.The researchers compared expressed genes in the hypothalamus of naked mole rats with those in leafcutter ants, specifically between forager and nurse subcastes of naked mole rats and the ants that labor outside the nest (foragers and defenders) and inside (carers and fungal gardeners). There was overlap between the differentially expressed genes from forager naked mole rats and out-nest ants, and also between nurse naked mole rats and in-nest ants.

The concept of a clear caste structure in naked mole rats “is hotly debated” among researchers in the field, says Yuki Haba, a postdoctoral fellow in Ishmail Abdus-Saboor’s lab at Columbia University, who was not involved in the study. In fact, a 2021 study found naked mole rats do not specialize in certain work tasks—rather, their roles may vary according to their age. Therefore, the division of labor in naked mole rat colonies might not be directly comparable to that of ants, Haba says. Glastad agrees, noting that when the naked mole rats were sampled in the new study, they were “specifically collected for doing those different behaviors.”

Still, the “results are striking,” Haba says. They show there may be some underlying shared biology between ants and mammals, he adds.

Glastad and his colleagues also treated naked mole rat astrocytes with ant NPA, even though the rats do not have NPA or the receptor for it. NPA-treated naked mole rat astrocytes cultured from foragers showed gene upregulation and those cultured from nurses showed downregulation. “Their gene expression changed in a way that was consistent with neuroparsin possibly being able to plug into something, and our guess is the insulin receptor in mammals,” Glastad says.

That work “opens up many hypotheses and questions,” Haba says. He would like to see more research into the results to confirm that NPA is acting on an insulin signaling pathway, he says.

The results in ants, and the similarities seen with the naked mole rats, demonstrate that “nature uses what it has,” Donaldson says. “It does lend a lot of credence to this idea that we’re not working with a huge number of molecules” that can control behavior.

Recommended reading

Single gene sways caregiving circuits, behavior in male mice

Robots marry natural neuroscience, experimental control to probe animal interactions

Coding bonus: Bats’ hippocampal cells log spatial, social cues

Explore more from The Transmitter

Novel neurons upend ‘yin-yang’ model of hunger, satiety in brain

Imagining the ultimate systems neuroscience paper