Amina Abubakar translates autism research and care for Kenya

First an educator and now an internationally recognized researcher, the Kenyan psychologist is changing autism science and services in sub-Saharan Africa.

KILIFI, KENYA—On a hot Thursday morning in November, developmental psychologist Amina Abubakar is seeing patients at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Neuro Centre in Kilifi—a fast-growing town on Kenya’s coast. KEMRI serves as a catchment for Kilifi County Referral Hospital, which provides care for families from six rural subcounties.

The clinic buzzes with activity: Mothers balance toddlers on their laps, other caregivers wait patiently, and staff members dart between rooms. In the middle of the action is Abubakar, in her element. She stops near an expectant-looking grandmother waiting with her grandson on a wooden bench. Speaking softly to them, Abubakar’s tone blends curiosity and genuine care.

“The issues we address are very sensitive, very personal,” Abubakar says, explaining why she takes time to interact with people outside the exam room. “I wouldn’t know what a mother with a child with disability feels because that’s a special personal feeling.”

Abubakar makes her patients and their families feel seen and remembered, says Martha Kombe, a clinician who has worked at KEMRI for 15 years. That is perhaps in part because Abubakar is familiar with what these families experience; she has two autistic nephews who live in Sweden.

“My sister is privileged because she lives in Europe,” Abubakar says. “But what about mothers in Kilifi or other rural parts of Kenya who lack this support?” Witnessing the support available to her sister compared with the lack of services in Kenya inspired Abubakar about 10 years ago to try to bridge the gap.

Now in her 50s, Abubakar focuses exclusively on autism as a senior research scientist at KEMRI. She is professor of developmental psychology and director of the Institute for Human Development at Aga Khan University in Nairobi, and she has held visiting appointments at the University of Oxford and Auckland University.

In addition, Abubakar routinely collaborates with researchers around the world to expand autism screening and diagnosis in Kenya, especially in rural areas, and she works with governmental agencies and nongovernmental organizations to increase research funding and improve services. “Preventing child mortality superseded everything else,” she says, when she began approaching funders and policymakers, and so she found ways to highlight how helping children with neurodevelopmental conditions would help them survive.

Abubakar’s ability to connect with people—in a busy clinic, university hall or government office—has been vital to her success, her colleagues say. Charles Newton, professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford, first met Abubakar in 2004 when she began her graduate studies. “She [was] one of the best Ph.D. students that I have had the privilege to work with,” he says.

The pair has collaborated extensively ever since: at the KEMRI Wellcome Trust Research Programme, a facility in Kilifi that combines epidemiological, social, laboratory and clinical research; on the NeuroDev Kenya study, which aims to understand the genetic and environmental factors that influence neurodevelopmental conditions in Africa; and on the SPARK project to support families of young children with developmental disabilities through caregiver training.

“In essence,” Newton says, “she is a shining light of autism research in sub-Saharan Africa.”

A

bubakar’s empathy for people with disabilities had an early start. Born and raised in Kanduyi, a village in an agriculturally rich area in Western Kenya, Abubakar was the 11th of 12 siblings. Her early life was shaped by her mother, who was visually impaired.Her mother prized education, and Abubakar initially trained as a teacher at Moi University, Eldoret, Uasin Gishu County in Kenya’s Great Rift Valley. She later decided to study educational psychology at Kenyatta University, where she became a reader for other students and for a lecturer with visual impairment. After teaching for more than a year at Bungoma High School in Western Kenya, however, Abubakar realized she wanted to become a researcher, and in 2008 she completed a Ph.D. at Tilburg University.

At that point, she says, she wanted to dedicate her work to identifying children and adolescents with a greater likelihood of being diagnosed with cognitive difficulties or mental health conditions, including developmental conditions in general. She also wanted to develop community-based interventions and policy work to support these efforts, she says.

However ambitious these goals seemed in an academic setting, Abubakar soon discovered that the challenges on the ground in Kenya—as in many parts of Africa—are multifaceted and include social stigma, limited access to experts and prohibitive costs. “In many rural communities, mothers are often blamed when their children have disabilities,” she says. Autism is sometimes attributed to witchcraft or viewed as a curse or bad omen.

Abubakar says she often meets families torn apart by such misconceptions or under strain after spending significant resources to find answers. “Facilities that offer specialized services for children with autism are rare and expensive,” she says. “Many parents sell property to get help, only to face disappointment” when centers are unable to provide meaningful autism services.

In an effort to meet that need, Abubakar helped to develop a caregiver skill training program in collaboration with the World Health Organization, which she deployed in Kenya in 2022. One Kilifi mother, she says, told her that until she took part in that program, she had believed her child might be unteachable.

A

key step to help families with autistic children in Kenya is improving screening and diagnosis, Abubakar says. To that end, she has collaborated with colleagues at the University of Cape Town and the University of Liverpool to produce an open-access instrument for autism screening and diagnosis that can be used in schools and health centers.“She has been leading the development of culturally appropriate tools for diagnosis of autism in sub-Saharan Africa,” Newton says. “She has incredible insights into the psychometrics of these tools.”

For Abubakar, the throughline in all of her efforts is finding ways to see science support the people most in need. “We need to ensure that our research positively impacts the lives of those we work with,” she says. “Autism is both a medical and social issue, and it’s time we address it with the urgency and compassion it deserves.”

Back in Kilifi, where services were once nonexistent, Abubakar starts each day at the KEMRI clinic by meeting in person with local scientists on the NeuroDev project. Again, her knack for connecting with others shines. She asks her mentees—a mix of young clinicians and graduate students—about their latest challenges and successes.

Her graduate student Eva Mwangome describes progress on a new initiative to provide earlier diagnoses and thereby reduce stigma among caregivers of children with developmental disabilities. “What you’re doing is important; don’t forget that,” Abubakar tells Mwangome, her face alit with warmth and pride.

Mwangome, who studies at the Open University in the United Kingdom, says she appreciates Abubakar’s encouragement in data collection and writing and publishing papers that can build awareness of their work in Kilifi. “She has been amazing. She has created a lot of opportunities not only for me but also for colleagues,” Mwangome says.

For Abubakar, this task is just as essential as research and providing services. “Our legacy is the next generation of African research scientists. We want the young ones to take this work forward.”

Recommended reading

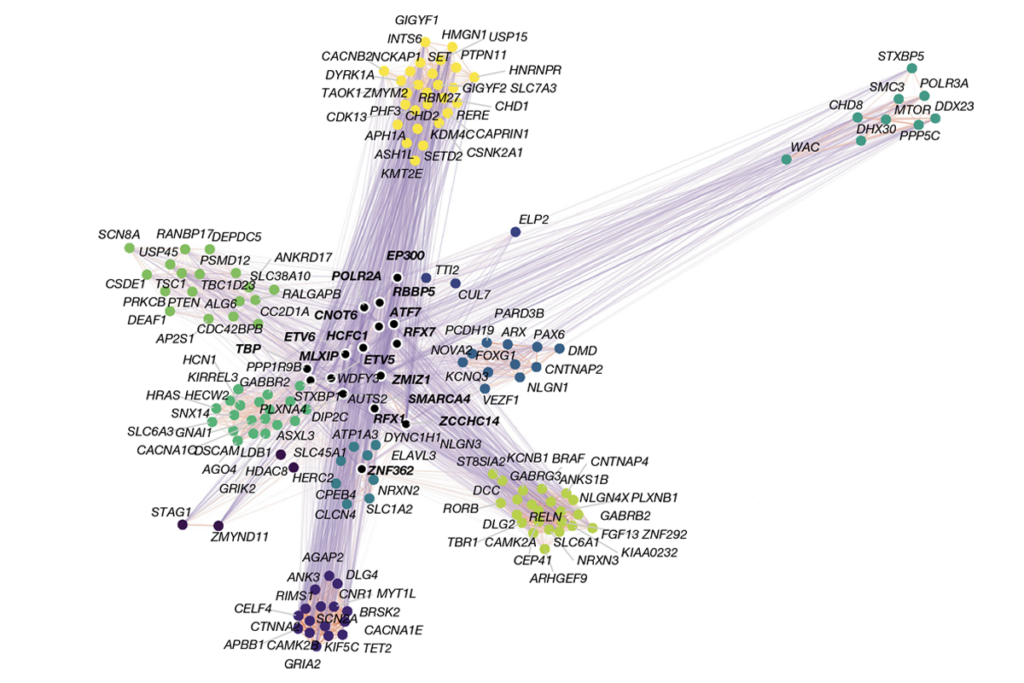

Organoid study reveals shared brain pathways across autism-linked variants

Sex bias in autism drops as age at diagnosis rises

Explore more from The Transmitter

Anti-seizure medications in pregnancy; TBR1 gene; microglia