Deep brain structures—including the striatum and thalamus—are more dysregulated in some people with autism than was previously recognized, according to two new preprints that analyze multiple brain regions.

During mid-gestation, genes linked to profound autism are most active in the thalamus, one of the studies found. And people with variants and chromosomal alterations linked to the condition show major changes in gene expression in the striatum, according to the other paper. Both studies, which were posted on bioRxiv in November, found more pronounced effects in those regions than in the cerebral cortex.

Most gene-expression research on autism to date has focused on the cerebral cortex. But “there is more to autism than the cortex,” says Omer Bayraktar, an investigator on one of the studies and cellular genetics group leader at the Wellcome Sanger Institute. “It’s time we pay strong attention to this.”

The findings chime with reports that subcortical structures are more affected by autism-linked microdeletions than cortical regions are: Corticothalamic organoids show stronger transcriptional responses to 22q11.2 deletion than do cortical organoids, according to a 2024 Cell Stem Cell paper.

But findings published more than a decade ago that point to the cerebral cortex as a major hub for autism-linked gene expression during human fetal development may have discouraged investigation into the rest of the brain, says Tomasz Nowakowski, associate professor of neurological surgery, anatomy and psychiatry, and of behavioral sciences, at the University of California, San Francisco, who was involved in the Cell Stem Cell paper and both of the new studies.

“There is sometimes an inclination to stay away from brain-wide analyses because we think we know where to look for these alterations,” Nowakowski says.

I

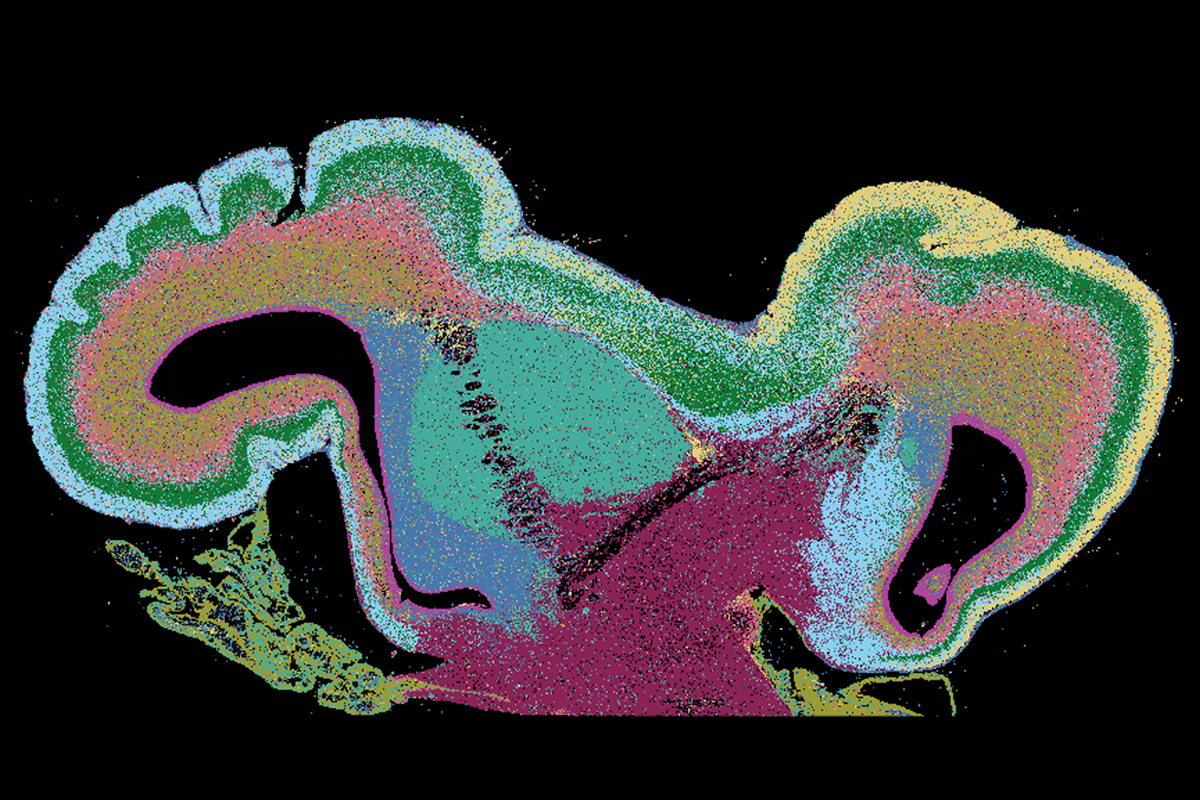

n those older studies, investigators were limited to bulk-sequencing brain tissue. Weak gene expression across swathes of the cortex could generate a larger signal than strong expression in a small population of subcortical cells.But advances in single-cell sequencing have helped to adjust gene-expression data based on cell-type abundance. When Bayraktar and his colleagues used single-cell spatial transcriptomics to analyze the expression of 250 autism-linked genes across the prenatal human forebrain, far more genes turned up in the thalamus than in the cortex, the new study found.

Most activity occurred in a small number of brain regions: 84 of the genes are strongly expressed in the thalamus, 49 in the germinal zones and 10 in the rest of the cortex. (The remaining genes are switched off or weakly expressed during development.)

Within the thalamus, most genes associated with autism—including SHANK2, SCN2A and ANK2—are expressed in excitatory neurons, the study also found. And expression of autism-linked genes in the germinal zones is mainly restricted to the medial ganglionic eminence, where interneurons are spawned.

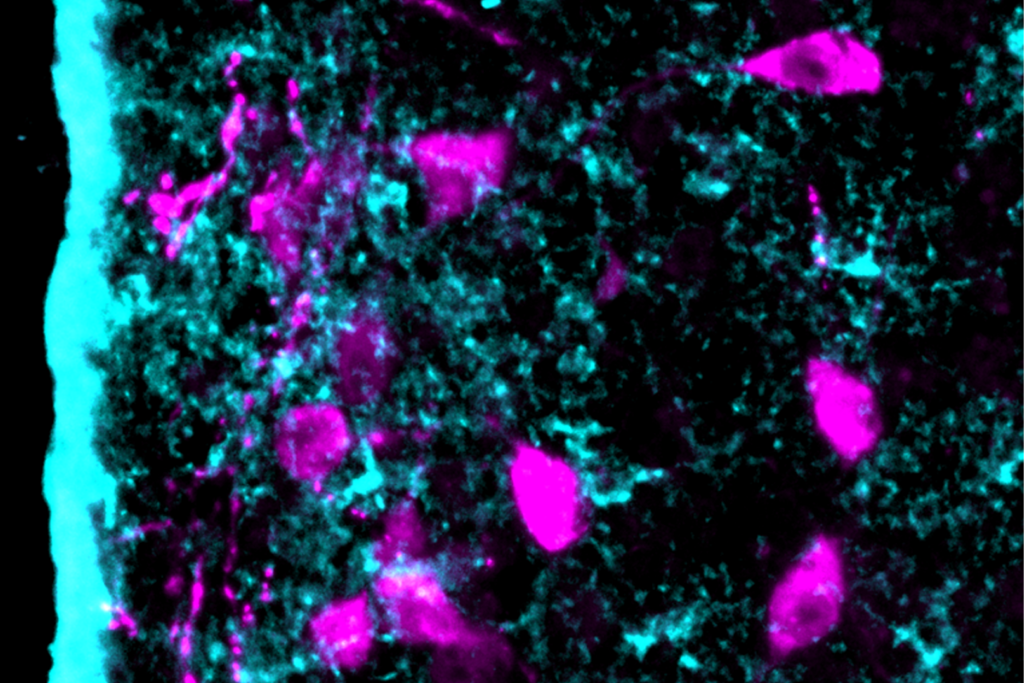

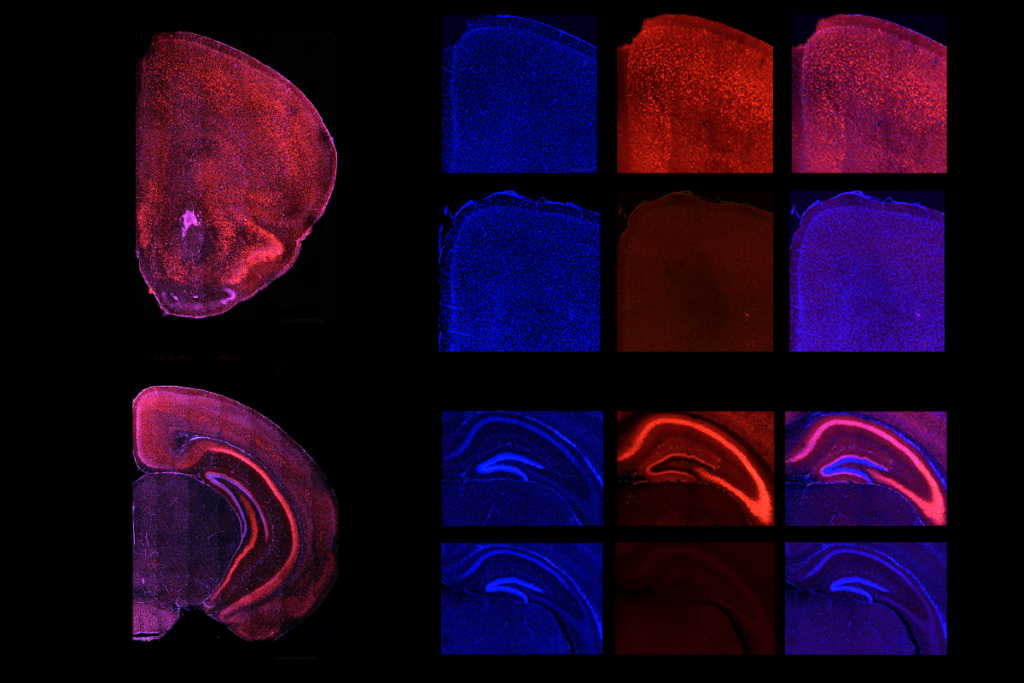

In the second paper, Nowakowski’s team analyzed cell-type development and gene-expression changes across five brain regions—the cortex, hippocampus, striatum, thalamus and olfactory bulb—in mice missing the chromosomal region 16p11.2. The striatum showed the most dramatic changes in its cellular makeup—most notably, inflated populations of medium spiny neurons. Those cells also display more transcriptional changes than do other cell types, the study found.

Whereas the cells’ contribution to autism is only just emerging, medium spiny neurons have long been implicated in neuropsychiatric conditions. The new work hints that 16p deletions might disrupt the same striatal pathways that are dysregulated in people with schizophrenia and similar conditions, says Ricardo Dolmetsch, professor of neurobiology at Stanford University, who also documented inflated populations of a subtype of medium spiny neurons in mice missing 16p11.2 back in 2014.

“This is sort of good news, in a way. It points to other psychiatric diseases that we understand better,” says Dolmetsch, who did not contribute to either of the new preprints.

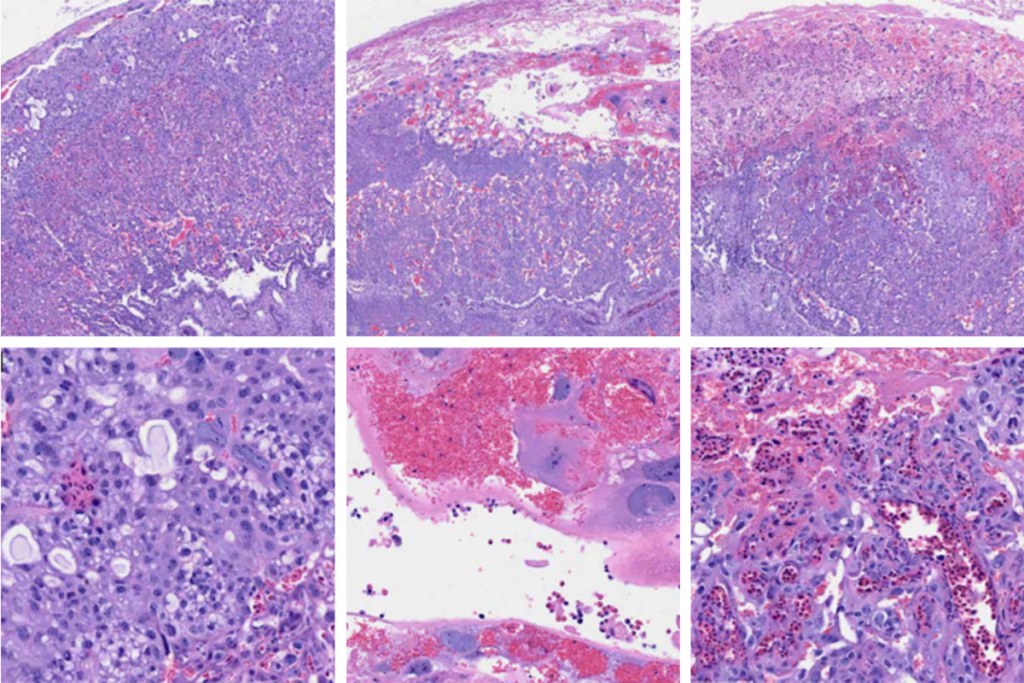

Looking deeper into those changes, Nowakowski and his colleagues analyzed postmortem striatal samples from 47 people with autism and 37 people without the condition. Autistic people have elevated numbers of medium spiny neurons that express the D1 dopamine receptor, the study found.

A D1 subtype that is localized to the striosome—neurochemically distinct pockets of the striatum—show the largest transcriptional changes. Among the dysregulated genes, many are associated with autism or other neurodevelopmental conditions.

T

he findings corroborate another preprint that reported changes in medium spiny neurons in 16p11.2-deficient mice. That study, which was posted on bioRxiv last year, noted sex-specific differences in gene expression in medium spiny neurons and deficits in reward learning—which is dependent on corticostriatal circuits—in male but not female mice.Though the new study didn’t detect any sex differences in gene expression, “we need to think about this from a sex-specific angle,” says Ted Abel, chair of neuroscience and pharmacology at the University of Iowa, who was involved in the earlier preprint but not the new studies.

In any case, evidence for subcortical involvement in autism is becoming hard to ignore, says Thomas Nickl-Jockschat, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Iowa, who collaborated with Abel on the unpublished study. Instead of “cluster-bombing” neurotransmission across the brain, researchers interested in developing therapies ought to target select circuits, including thalamocortical pathways, he adds.

Still, it’s unclear how changes in medium spiny neurons affect circuit function, and whether subtypes found in striosomes function differently from subtypes in the rest of the striatum. Answers to those questions may arise from the first complete atlas of the developing basal ganglia in mice, says Hongkui Zeng, director of the Allen Institute for Brain Science, who is working on the atlas but was not involved in the new work. That map—due to be released next year—charts when distinct subcortical cell types emerge during development and could help uncover the functions of striatal cell types, Zeng says.

“I think this is going to be a major frontier for autism research,” Nowakowski says.