Behavioral test taps multiple senses in mice

A new behavioral test that gauges how well mice simultaneously process light and sound may help explain and treat problems with this skill in people with autism.

A new behavioral test gauges the ability of mice to simultaneously process light and sound. The procedure, described 12 January in Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, could help decipher and treat problems with this skill, which are common in people with autism1.

Most people benefit from using multiple senses to navigate their environment. For instance, people can understand spoken language better when they can also see a person’s lips moving. But individuals with autism tend to have difficulty integrating information from two or more senses, making environments with many stimuli sometimes seem overwhelming.

In the study, researchers used their novel setup to assess how well typical mice combine stimuli while performing simple tasks. The work lays the groundwork for investigating multisensory processing deficits in mice displaying features of autism.

Researchers placed each of nine mice in a chamber with three nose-sized holes and taught the mice to respond to lights and noises to reap a reward. For example, when a flashing light appeared in a hole, a mouse received a sip of a vanilla-flavored drink if it poked its nose in that hole. In another task, a mouse was rewarded for responding to white noise by choosing the hole on the right and to a high-pitched tone by nosing its way into the one on the left.

The researchers then exposed the mice to combinations of visual and auditory stimuli as cues to stick their noses into a particular hole. As expected, the mice stuck their noses into the correct holes most often when given both stimuli at the same time. The findings confirm that mice, like most people, are better able to choose the proper response to a situation when they are exposed to multiple stimuli.

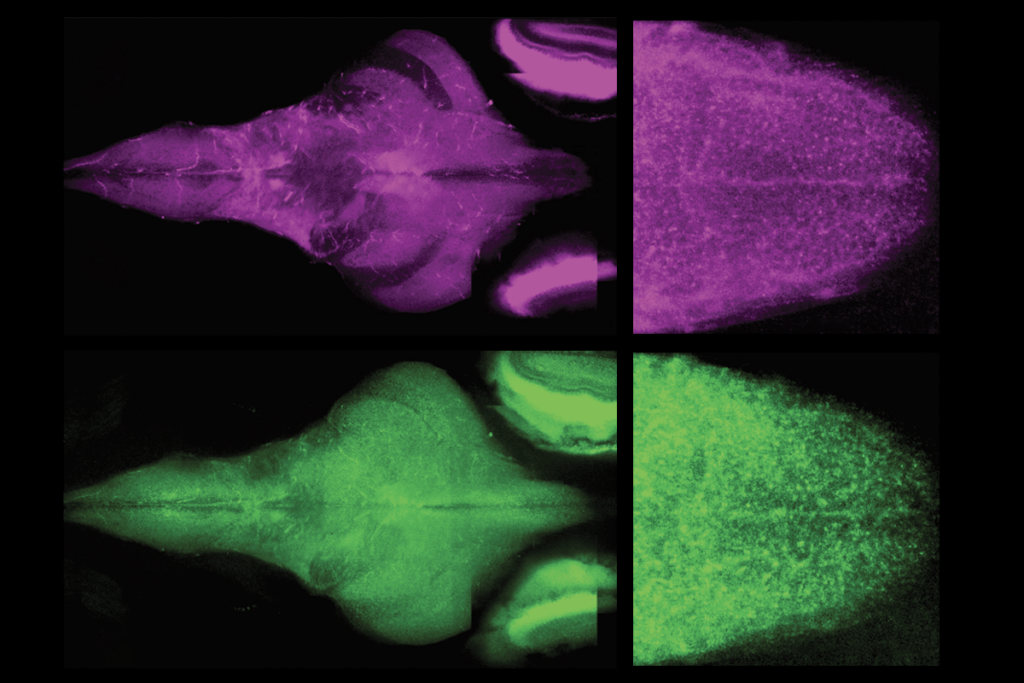

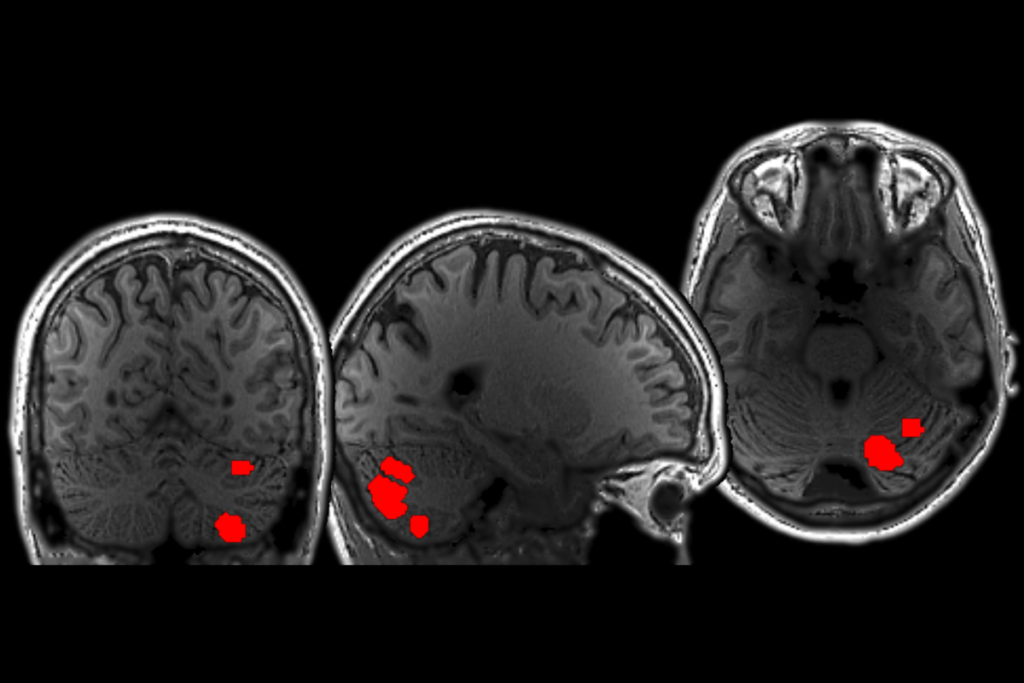

The researchers are using their technique in mice with autism-like social, communicative and repetitive behavior problems to determine whether multisensory processing is altered in these animals. If it is, they plan to treat the mice with drugs to see if any soften their sensory overload. They also say that the test may allow researchers to trace the brain circuits involved in integrating sensory information — and pinpoint the precise glitches in those networks when the process goes awry.

References:

1. Siemann J.K. et al. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 8, 456 (2015) PubMed

Recommended reading

Largest leucovorin-autism trial retracted

Pangenomic approaches to the genetics of autism, and more

Latest iteration of U.S. federal autism committee comes under fire

Explore more from The Transmitter

Cerebellum responds to language like cortical areas

Neuro’s ark: Understanding fast foraging with star-nosed moles