Behavioral therapy normalizes activity in autism brains

Pivotal response training, a form of behavioral therapy for autism, alters brain activity in children with the disorder, normalizing it in some regions and triggering compensatory activity in others, according to a small study. The unpublished results were presented Wednesday at the International Meeting for Autism Research in San Sebastián, Spain.

Pivotal response training (PRT), a form of behavioral therapy for autism, alters brain activity in children with the disorder, normalizing it in some regions and triggering compensatory activity in others, according to a small study presented yesterday at the International Meeting for Autism Research in San Sebastián, Spain.

“What we found is quite stunning: Areas we thought failed to develop can, with minimal treatment, be brought into working order,” says lead investigator Kevin Pelphrey, director of the Yale Child Neuroscience Lab.

He says the activity patterns may be useful for measuring the effectiveness of behavioral or drug therapies.

PRT is a play-based, child-initiated therapy derived from the widely used applied behavioral analysis. It involves training children in so-called ‘pivotal responses,’ including motivation and social initiation.

The therapy is a core component of the Early Start Denver Model, one of the best-studied therapies for autism. A study published last year using that model suggested that it normalizes brain activity in young children with autism, as measured by electroencephalography, but it did not compare brain activity in the children before and after treatment.

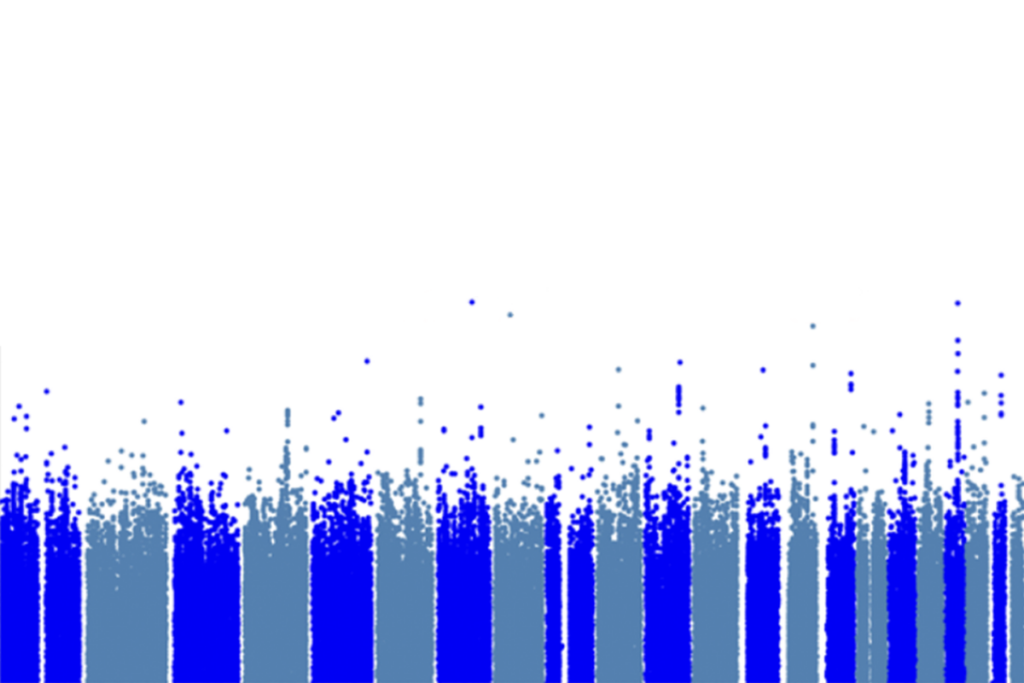

In the new study, ten children aged 4 to 7 with autism practiced PRT for four months, undergoing brain imaging before and after the course of therapy. PRT normalized their brain activity in a number of brain regions, including the right posterior superior temporal sulcus, left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, amygdala and fusiform gyrus, all brain areas involved in social interactions. These changes correlate with behavioral improvements, such as better eye contact and ability to make conversation.

Pelphrey and his collaborators have previously shown that children with autism have abnormal activity in these brain regions when looking at biological motion, such as a person walking.

The therapy also boosts activity in other areas, including the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which Pelphrey’s team has previously identified as compensatory areas — brain regions that are more active in unaffected siblings of children with the disorder.

Pelphrey and his colleagues plan to look for patterns of brain activity before therapy that might predict who is most likely to respond to PRT. “Our prediction is that there is already some compensatory mechanism there,” he says, meaning activity in the compensatory regions. All the children in the study responded to the therapy, so the researchers haven’t yet been able to identify predictors.

They are currently studying a larger group of children, including more girls than before. They also aim to look at how oxytocin, a hormone therapy being tested for autism, can enhance response to therapy.

For more reports from the 2013 International Meeting for Autism Research, please click here.

Explore more from The Transmitter