Over the past decade, autistic people and their families have increasingly experimented with medical marijuana and products derived from it. Many hope these compounds will alleviate a range of autism-related traits and problems. But scientists are still in the early stages of rigorous research into marijuana’s safety and effectiveness, which means that people who pursue it as treatment must rely mostly on anecdotal information from friends and message boards for guidance.

Here we explain what researchers know about the safety and effectiveness of cannabis for autism and related conditions.

What is medical marijuana?

Medical marijuana generally refers to any product derived from cannabis plants — including dried flowers, resins and oils — that has been recommended by a doctor. It may be consumed directly or infused into an array of foods, lozenges and candies. These products have become popular among autistic people and their families for treating a broad swath of conditions, including insomnia, epilepsy and chronic pain.

Depending on the strain of the plant and the processing methods used, these products contain varying levels of active ingredients, including tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) — responsible for the ‘high’ associated with marijuana — and cannabidiol (CBD), which is minimally psychoactive. Much of the research on medical applications focuses on CBD. There are also more than 500 other compounds in marijuana that may affect people’s behavior and cognition1.

Is medical marijuana legal?

Yes and no. Federal law in the United States classifies marijuana and its derivatives as ‘Schedule 1’ drugs, meaning that they have no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. Schedule 1 drugs are illegal, and research on them requires labs to follow strict security protocols and adhere to regular facility inspections.

In 33 states, along with the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, however, people can legally buy and use medical cannabis for certain approved conditions, such as seizures and sleep problems, although the list of qualifying conditions varies by state. These same states, plus 13 others, also allow CBD oil. Fourteen states plus Puerto Rico have approved medical marijuana for autism, and some additional states may allow it for autistic people at a doctor’s discretion.

Under U.S. federal law, CBD products manufactured from industrial hemp are legal as long as they contain no more than 0.3 percent THC. And in some states, CBD oil is permitted to contain up to 5 percent THC.

In many states where medical marijuana is legal, licensed dispensaries sell products that have been tested by accredited laboratories to verify the presence of active ingredients and the absence of contaminants. Some states permit individuals or their licensed caregivers to grow their own cannabis plants for personal use. Most states in the U.S. require people who use medical marijuana to register and get a special identification card.

In many European countries, as well as in Australia, Canada, Israel and Jamaica, medical cannabis is legal, with specific laws varying from country to country.

Are there any cannabis-derived drugs approved to treat autism or related conditions?

To date, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved only one cannabis-derived drug: Epidiolex. It is a liquid cannabis extract containing purified CBD that can decrease seizures in people with Dravet syndrome or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome — severe forms of epilepsy that are sometimes accompanied by autism — and in those with tuberous sclerosis complex. It is available only by prescription, and only for these three conditions.

GW Pharmaceuticals, the company that makes Epidiolex, is conducting a trial of the drug for Rett syndrome, a neurodevelopmental condition related to autism. The Rett syndrome trial is not focused on alleviating seizures, but on improving cognitive and behavioral problems. The company is also recruiting autistic children and teenagers for a phase 2 trial of cannabidivarin, another component of cannabis. That trial will examine cannabidivarin’s effect on a range of traits in autistic children, including repetitive behaviors, and on quality of life.

How might cannabis help autistic people?

Epidiolex’s success has spurred many parents to try marijuana and cannabis extracts for seizures, behavioral issues and other autism-related traits in their children, but experts warn that these drugs remain largely untested for such purposes. Some studies on cannabinoids have shown promising results in animal models and in early-stage clinical trials, but this research does not yet support their widespread use.

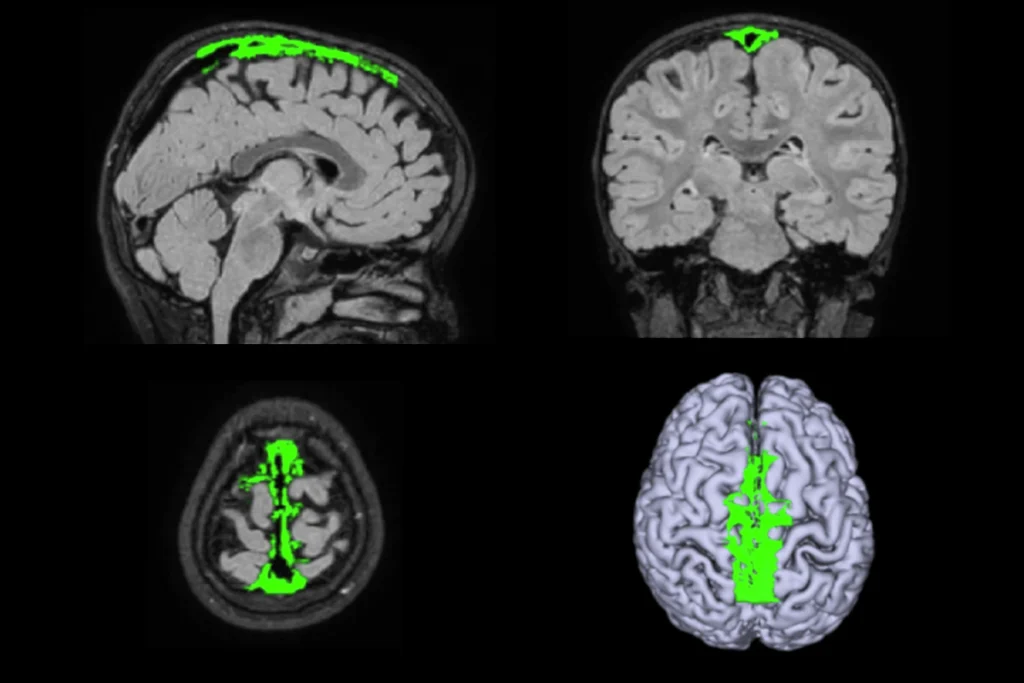

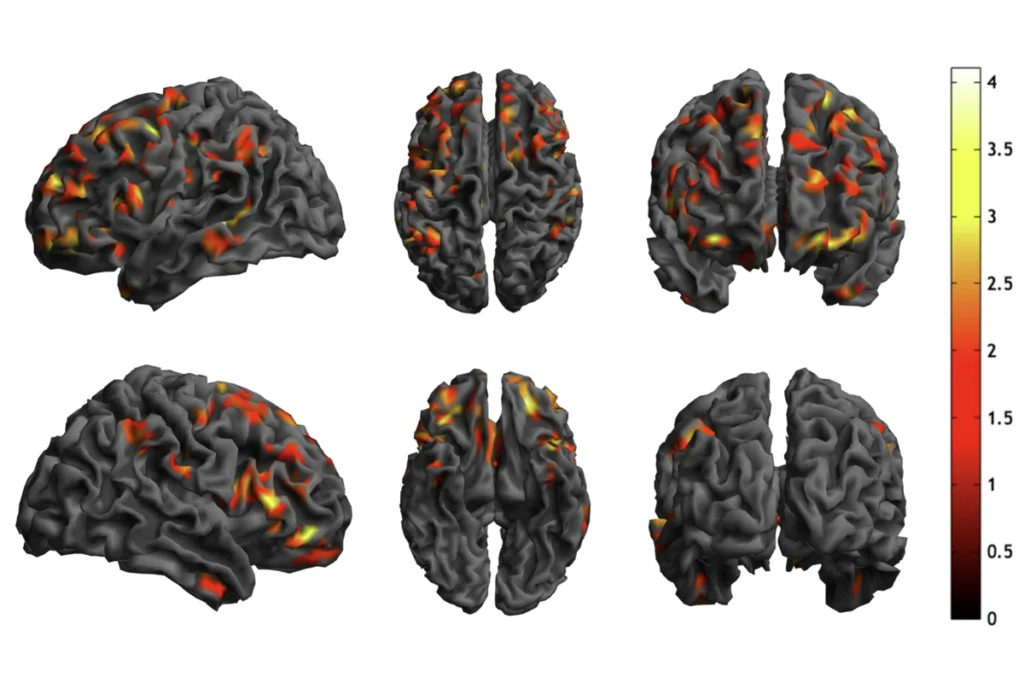

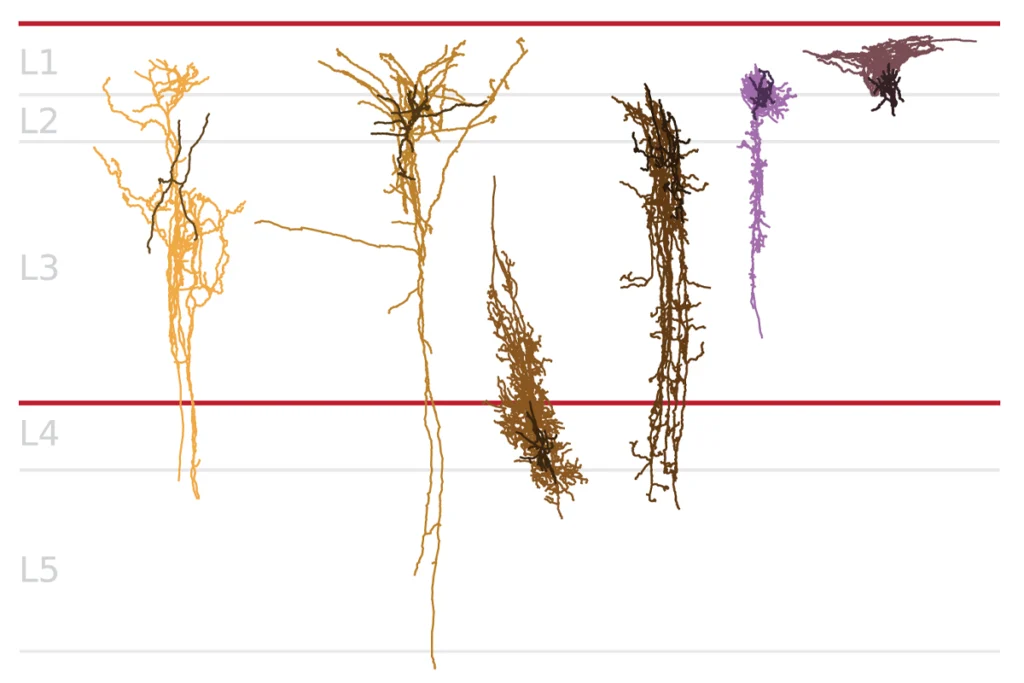

Cannabis’ active ingredients are thought to exert their effects by binding to proteins called cannabinoid receptors in the brain: THC activates the CB1 and CB2 receptors, whereas CBD seems to block them2.

Both types of cannabinoid receptors are located in neurons in the brain and throughout the body. The brain contains more CB1 than CB2 receptors, and the activation of each receptor type affects a range of ion channels and proteins involved in cell signaling3. The ultimate effects of cannabinoid receptor activation depend on which body system they belong to. For instance, the activation of CB1 receptors in the brain can either increase or decrease neuron excitability, depending on which kind of neuron a cannabinoid binds to; activation of CB2 receptors in the digestive system can decrease inflammation4,5.

Blocking the CB1 receptor can relieve seizures and memory issues in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome, a condition related to autism, according to a 2013 study in Nature Medicine6. A 2018 clinical trial of a synthetic CBD drug by the drug maker Zynerba showed significant improvements in anxiety and other behavioral traits in people with fragile X. Cannabinoid receptor activation has also been shown to lead to memory improvements in fragile X mice7.

Research has also demonstrated that CBD alleviates seizures in children with CDKL5 deficiency disorder, an autism-linked condition that is characterized by seizures and developmental delay. CBD also lessens seizures and improves learning and sociability in a mouse model of CDKL5 deficiency disorder.

Complicating the picture, CBD alone may not be sufficient for cannabis’ therapeutic effects. A 20-to-1 ratio of CBD to THC relieves aggressive outbursts in autistic children, a 2018 study suggests8. This same ratio of compounds significantly improved quality of life for some children and teenagers with autism in a 2019 study9. Specifically, researchers observed significantly fewer seizures, tics, depression, restlessness and outbursts. Most participants reported improvements, and about 25 percent of participants experienced side effects such as restlessness.

Cannabis may have effects that go beyond the cannabinoid receptors, too. Mice that ingested CBD over extended periods of time displayed changes to DNA methylation in sections of the genome associated with autism, a 2020 study showed10. The researchers suggested that epigenetic changes may be at least partly responsible for CBD’s behavioral effects, though they did not directly examine the mice’s behavior.

Is cannabis safe?

It’s unclear. Large doses are usually not fatal, but taking it regularly may have long-term effects.

Based on the clinical trials of Epidiolex, the FDA warns that the drug could cause elevated liver enzymes, which can be a sign of liver damage. This is especially likely in people who take Epidiolex and the epilepsy drug valproate at the same time.

CBD is considered minimally psychoactive, but many preparations of it contain undisclosed amounts of THC, which may lead to inadvertent intoxication and impairment.

Many studies have shown that cannabis treatment carries only minor side effects such as sedation or restlessness, but these studies have not looked at long-term side effects. Researchers still don’t have a solid grasp on how the active ingredients in marijuana actually affect the brain, nor do they know how these compounds might impact a child or teenager’s developing brain or interact with other medications.

Some research has shown that recreational marijuana use beginning in one’s teenage years can have negative long-term effects on cognition11. But experts note that the dosages used for medical purposes are often quite lower than those used in a recreational context.

Are some cannabis products safer or more effective than others?

Many people who self-administer cannabinoids for epilepsy or other conditions cultivate it at home. Others purchase it directly from companies rather than buying it at state-licensed dispensaries, and research has shown that these products are not created equal.

The actual potency of CBD products varies widely from their advertised concentrations, according to a 2017 study in JAMA, and some products contain more than the legal limit of THC — potentially enough to cause intoxication, especially in children12. Less than one-third of the products tested contained within 10 percent of the advertised CBD concentration, and THC was detected in about 21 percent of samples.

In a presentation at the 2020 meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, researchers concluded that ‘artisanal’ CBD products available for purchase online and in health-food stores are not as effective at controlling seizures as pharmaceutical-grade CBD.