Daniel Geschwind: After many detours, on the trail of autism’s genetics

In the late 1990s, after Daniel Geschwind had established himself as an expert on the genetics of neurological diseases, a personal connection abruptly pulled him into autism research. Since then, he has participated in dozens of studies probing the genetic basis of autism and related neuro-developmental disorders.

In the fall of 1979, after three months of living with a French family in the Loire Valley, 19-year-old Daniel Geschwind decided not to return to his undergraduate studies in chemistry at Dartmouth College. Instead, he stayed in France for a year, filming, producing, editing and starring in a series of professional ski movies. “I was curious about filmmaking at the time,” he recalls matter-of-factly. “And it was really a lot of fun.”

Over the following 25 years, Geschwind continued to follow his bliss, building an unconventional, but thoroughly successful, career. When, at age 23, he finally finished his chemistry degree, he took a detour into business consulting before beginning an M.D./Ph.D. program focused on neurobiology. In the late 1990s, after he had established himself as an expert on the genetics of neurological diseases, a personal connection abruptly pulled him into autism research.

Since then, Geschwind has participated in dozens of studies probing the genetic basis of autism and related neuro-developmental disorders. In August 2001, he and other researchers affiliated with the Cure Autism Now nonprofit created the Autism Genetic Resource Exchange (AGRE) ― a gene bank of more than 4,500 samples from children with autism and their families1. Using samples collected through AGRE, Geschwind has led many of the largest high-resolution genome scans intended to pinpoint the chromosomal defects in people with autism.

“Dan Geschwind is a visionary,” says Clara Lajonchere, vice president of Clinical Programs at Autism Speaks which, in 2007, took Cure Autism Now under its umbrella. “He probably has his hand in one too many pots, but his commitment to autism research is ― well, he’s relentless.”

Family ties:

Between 1965 and 1982 Geschwind’s father, Stanley, served as head of the Quantum and Solid-State Physics Department at Bell Labs, the prestigious New Jersey research outfit that became famous in the 1950s for developing the transistor and the laser. Stanley’s cousin, Norman Geschwind, a neurologist at Harvard Medical School who coined the term ‘behavioral neurologyʼ, was renowned for his studies of brain asymmetry, language and neuropsychiatric disease.

When it was time for Dan to choose a career, however, he wasn’t interested in taking up the family business. “I thought, well maybe I’ll be the only one in my family to ever make a decent living,” he says.

It was only after working at Boston Consulting Group, from 1982 to 1984, that he succumbed to a career in science. He enrolled in an M.D./Ph.D. program at Yale University, and chose to work with Pasko Rakic, the Yugoslavian neuroscientist who was the first to trace how brain cells develop in the cerebral cortex.

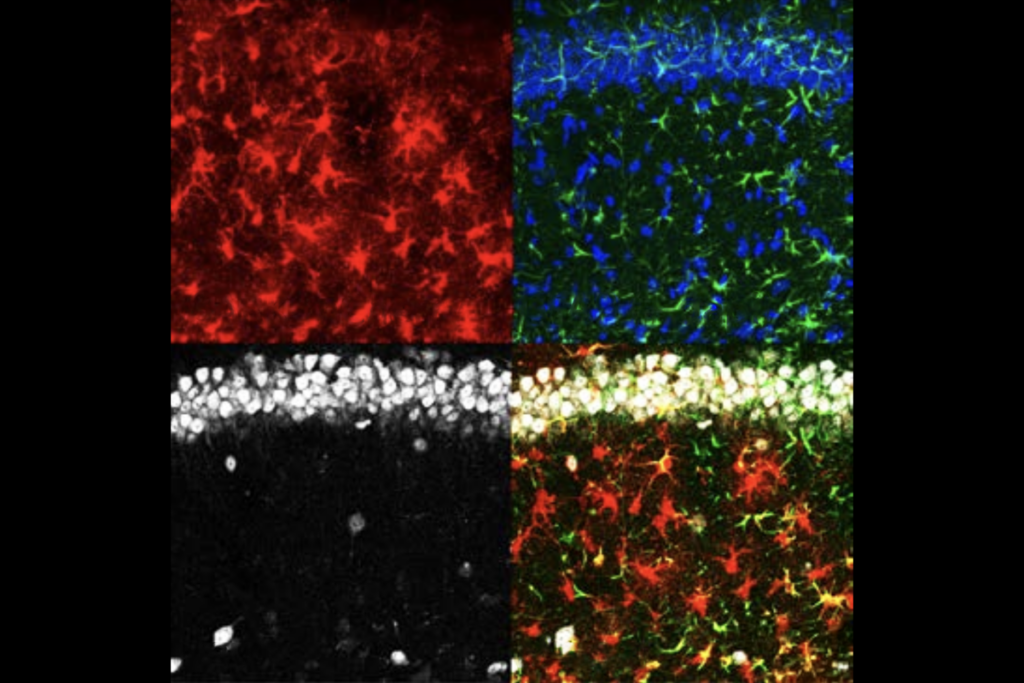

Geschwind was particularly impressed that Rakic studied higher cognition in primates, unlike most other neurobiologists who studied simpler systems in mice or insects. Geschwindʼs first scientific paper, published in 1989, mapped the distribution of specific neurotransmitter receptors ― proteins that receive chemical signals between nerve cells ― in the cortex of rhesus monkeys2.

| Moving pictures: Before he became a scientist, Geschwind made and starred in ski movies. |

To complete the medical portion of his degree, he chose a residency program at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), which seemed ripe for research in behavioral diseases. “It was a place where it seemed possible to bridge the disciplines,” he says.

There, Geschwind studied fronto-temporal dementia, a condition seen in middle-aged and elderly people in which portions of the brain’s frontal and temporal lobes shrink, leading to changes in personality, impulsivity and language comprehension. The disorder is asymmetric, meaning that the deficits occur only on one side of the brain.

What Geschwind found intriguing about fronto-temporal dementia, he says, is that which side of the brain becomes damaged is often hereditary: some families show shrinkage on the left side of the brain, others on the right3.

“That was remarkable to me, because it indicated that there had to be a connection between neuro-development and neuro-degeneration, even for a late-onset disease,” he says. “I believe that development is really the critical time window.”

Geschwind has always looked for big-picture connections in research, even when those connections are not obvious, Rakic says. “There is a risk in that,” Rakic notes. “It is safer to just do the same thing as everybody else.”

Unique insights:

As a junior faculty member at UCLA in the late 1990s, Geschwind met a woman who had two children with autism. Because he studied brain development, she encouraged him to contact Portia Iverson, a mother of a boy with autism and movie-set designer who had launched Cure Autism Now. Shortly after Geschwind met Iverson, he became the first chair of the rapidly growing organization’s scientific review committee.

After Cure Autism Now launched AGRE, in 2001, Geschwind’s lab became increasingly involved in studying the genetics of autism.

“If you’re interested, even in a more abstract way, in human behavior and human cognition, autism is an extraordinary window into that,” Geschwind says. “It involves dysfunction in social cognition, language ― the things that are really part of what makes us human.”

He adds that the autism field is “totally uncharted territory” for researchers, making it all the more appealing.

In particular, his lab is looking for genetic similarities among people with autism who share endophenotypes ― quantifiable markers of disease ― such as sex, language ability and social impairment.

In 2004, for instance, Geschwind’s team removed girls with autism from linkage study samples. When they compared only males with autism, they found shared genetic variations in the 17q11 chromosomal region4.

The following year, using data from 291 families in AGRE, the researchers found that children with autism who speak their first words at the same age share specific variations in the chromosomal regions 3q, 17q and 7q5.

In January 2008, following up on the 7q finding, Geschwindʼs team narrowed down the region to pinpoint a specific gene, Contactin Associated Protein-Like 2 (CNTNAP2), that is associated with autism and language deficits in males6. In November, the researchers linked CNTNAP2 to families with specific language impairment, another childhood development disorder7.

Scientists who have worked closely with Geschwind are simultaneously intimidated and inspired by this dogged approach.

“Thereʼs no doubt in his mind that weʼre going to find these genes, figure out what they do and get some sort of treatment out of it,” says Maricela Alarcón, who worked as a postdoctoral fellow in Geschwindʼs lab for three years and is now an assistant professor of neurology at UCLA. “When youʼre in the lab and just toiling away, and feel like youʼre not making any advances at all, he has that strength.”

Geschwind, the former strategic planner, does admit that “you’d need a crystal ball” to know where the rapidly growing autism field is headed.

“What weʼve learned most is that autism is far more heterogeneous than any of us expected,” he says. “But on the other hand, nowhere has there been more progress in genetics, in any complex disease, than in autism.”

Geschwind’s life outside the lab is no less rigorous. He plays tennis about twice a week, serves as a “taxi service” for his three children, keeps tabs on the ever-rocky financial markets, and collects wine.

His favorite pastime hasn’t changed since he was 19. In a good year, he says ruefully, he only has about 10 or 15 days to hit the double-black-diamond slopes of California’s Mammoth Mountain.

But Geschwind insists that he’s not a risk-taker. “It’s kind of like walking at some level,” he says. “I look down some of those slopes, and they’re just not that steep to me.”

References:

- Geschwind D.H. et al. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69, 463-466 (2001) PubMed ↩

- Lidow M.S et al. Neuroscience 32, 609-627 (1989) PubMed ↩

- Nasreddine Z.S. et al. Ann. Neurol. 45, 704-715 (1999) PubMed ↩

- Stone J.L. et al. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75, 1117-1123 (2004) PubMed ↩

- Alarcón M. et al. Mol. Psychiatry 10, 747-757 (2005) PubMed ↩

- Alarcón M. et al. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 82, 150-159 (2008) PubMed ↩

- Vernes S.C. et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 2337-2345 (2008) PubMed ↩

Recommended reading

INSAR takes ‘intentional break’ from annual summer webinar series

Dosage of X or Y chromosome relates to distinct outcomes; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

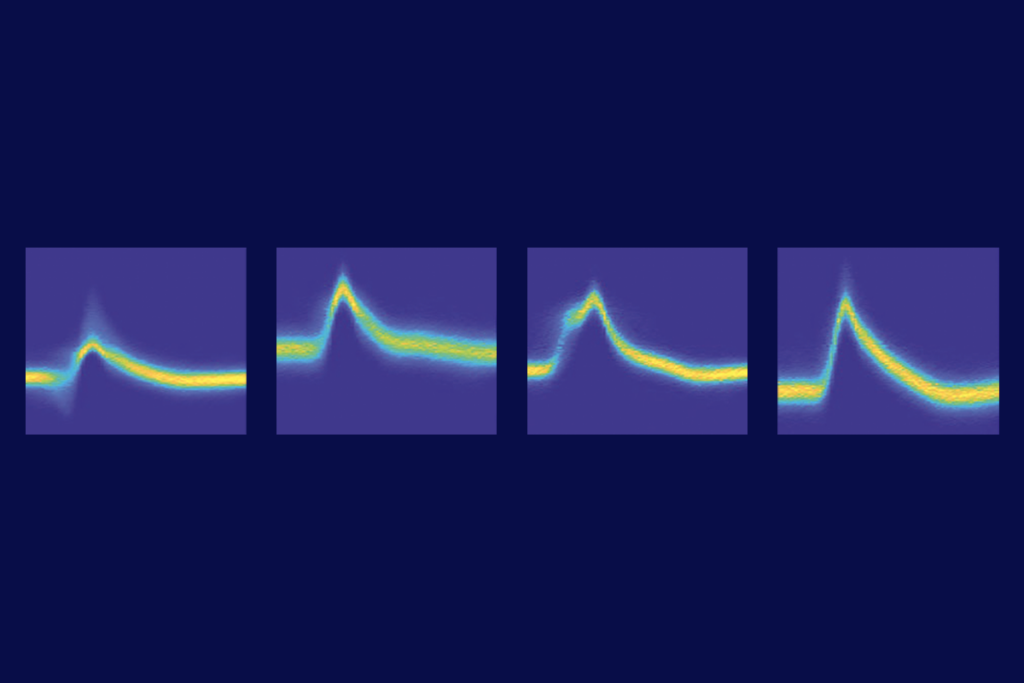

Null and Noteworthy: Neurons tracking sequences don’t fire in order