Device helps record neuronal activity in moving rats

A new device allows researchers to identify the precise source of an emitted brain signal measured in freely moving rats, according to a study published in the July issue of the Journal of Neurophysiology.

A new device allows researchers to identify the precise source of an emitted brain signal measured in freely moving rats, according to a study published in the July issue of the Journal of Neurophysiology1.

In another study, published 5 August in Nature Neuroscience, researchers used the new technique to track the differences between subtypes of neurons that inhibit signals in the brain2.

Researchers typically insert a small electrode right next to a neuron to measure the neuron’s activity. The emitted signal is sufficient to identify some families of neurons, such as fast-spiking inhibitory neurons, but not others.

What’s more, to identify a neuron’s subtype, researchers must label it with a specific compound using a glass pipette. Because the pipette breaks easily when the animal moves, however, this technique is only possible in anesthetized or restrained rodents.

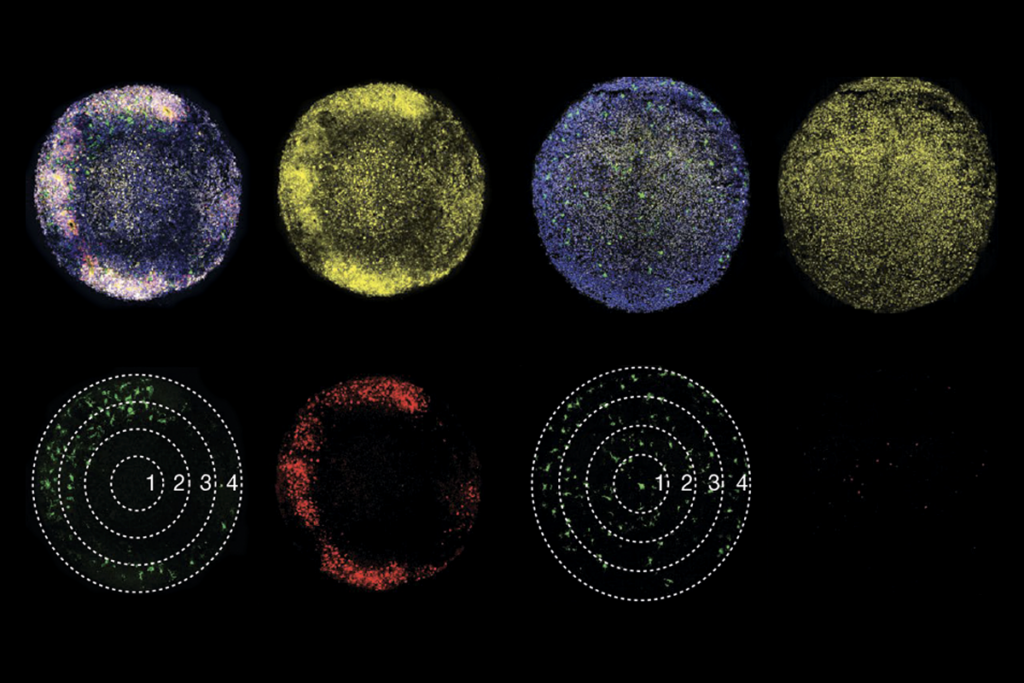

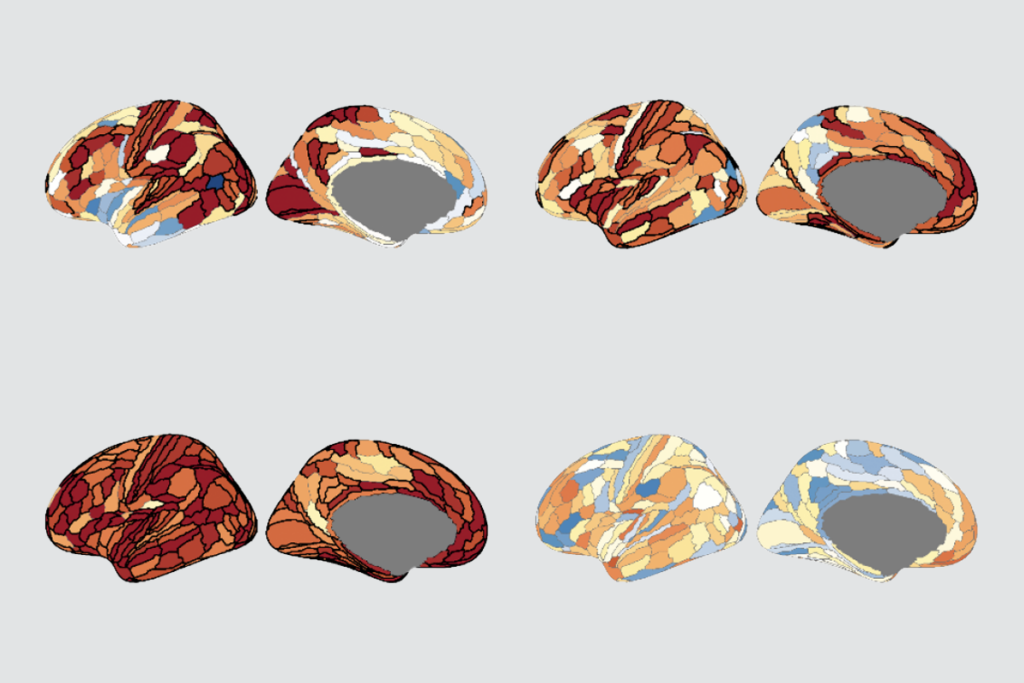

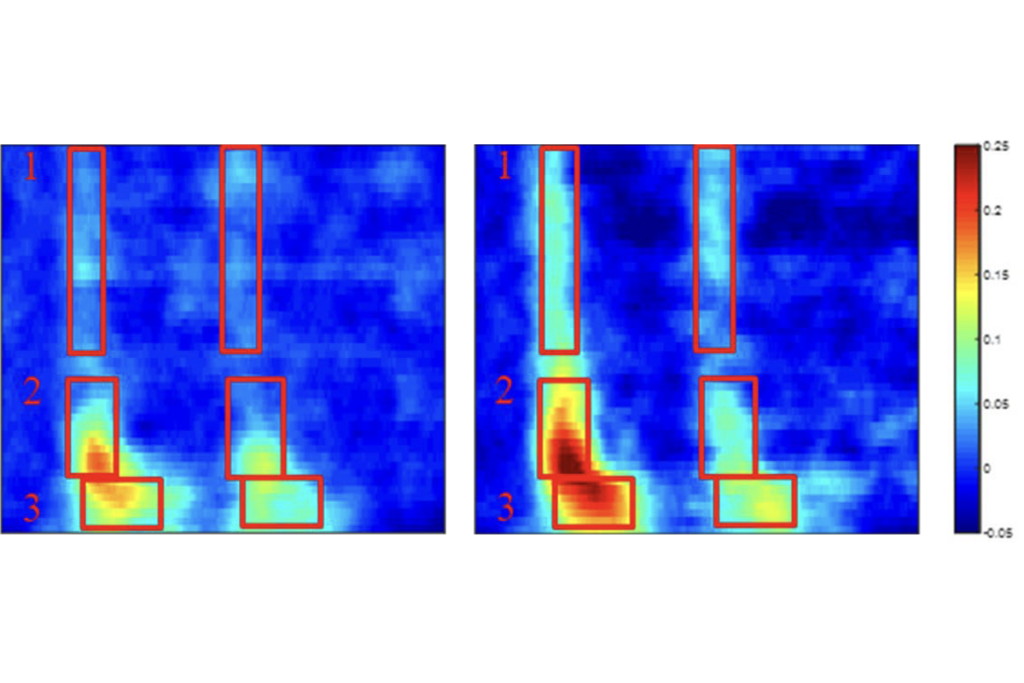

In the first new study, researchers built a device that can stabilize the pipette within a rat’s skull, preventing it from breaking. In the second study, an independent team of researchers used this technique to measure the activity of basket and ivy cells, two types of inhibitory neurons, while rats moved around their cages. The researchers used video monitoring and an accelerometer, a device that measures how quickly the rats move, to follow the rats’ activities.

Basket cells fire at different rates as the rats move around, sleep or sit quietly. For example, when rats pause between activities, the cells slow their firing. This suggests that these neurons function in a behavior-dependent manner, the researchers say. In contrast, ivy cells fire at the same rate regardless of what the rat is doing.

Researchers may be able to use this new technique to track neuronal activity during certain behaviors in mouse or rat models of autism. This information could help identify the best targets for correcting the behaviors.

References:

1: Herfst L. et al. J. Neurophysiol. 108, 697-707 (2012) PubMed

2: Lapray D. et al. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 1265-1271 (2012) PubMed

Recommended reading

Autism-linked copy number variants always boost autism likelihood

New findings on Phelan-McDermid syndrome; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Building the future of neuroscience at HBCUs

Emotion research has a communication conundrum