Facial expressions between autistic and typical people may be mismatched

Conversations between an autistic and a typical person involve less smiling and more mismatched facial expressions than do interactions between two typical people.

Conversations between an autistic and a typical person involve less smiling and more mismatched facial expressions than do interactions between two typical people, a new study suggests1.

People engaged in conversation tend to unconsciously mimic each other’s behavior, which may help create and reinforce social bonds. But this synchrony can break down between autistic people and their neurotypical peers, research shows. And throughout an autistic person’s life, these disconnects can lead to fewer opportunities to meet people and maintain relationships.

Previous studies have looked at autistic people’s facial expressions as they react to images of social scenes on a computer screen2. The new work, by contrast, is one of a growing number of experiments to capture how facial expressions unfold during ordinary conversation.

Changes in facial expressions are easy to observe but notoriously hard to measure, says John Herrington, assistant professor of psychiatry at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania. He and his colleagues devised a new method to quantify these changes over time in an automated and granular way using machine-learning techniques.

Atypical facial expressions are in part a manifestation of difficulties with social coordination, Herrington says. So tracking alterations in facial expression may be a useful way to monitor whether interventions targeting these traits are effective.

“This is a perfect tool to measure if [a change in autism traits] is happening,” he says.

Mismatched expressions:

The new study included 20 autistic people and 16 typical controls, aged 9 to 16 years and matched for their scores on intelligence and verbal fluency. Each participant engaged in two 10-minute conversations — first with their mother and then with a research assistant — to plan a hypothetical two-week trip.

To promote a positive and cooperative exchange, the researchers told participants not to focus on money or logistics. They recorded the conversations with two synchronized high-definition cameras, one pointed at each conversation partner. Later they analyzed the recordings using an automated facial expression algorithm. The algorithm tracked the frame-by-frame movements of two facial muscles used during smiling.

On average, less smiling occurred during conversations involving an autistic person, compared to exchanges with a control, the researchers found.

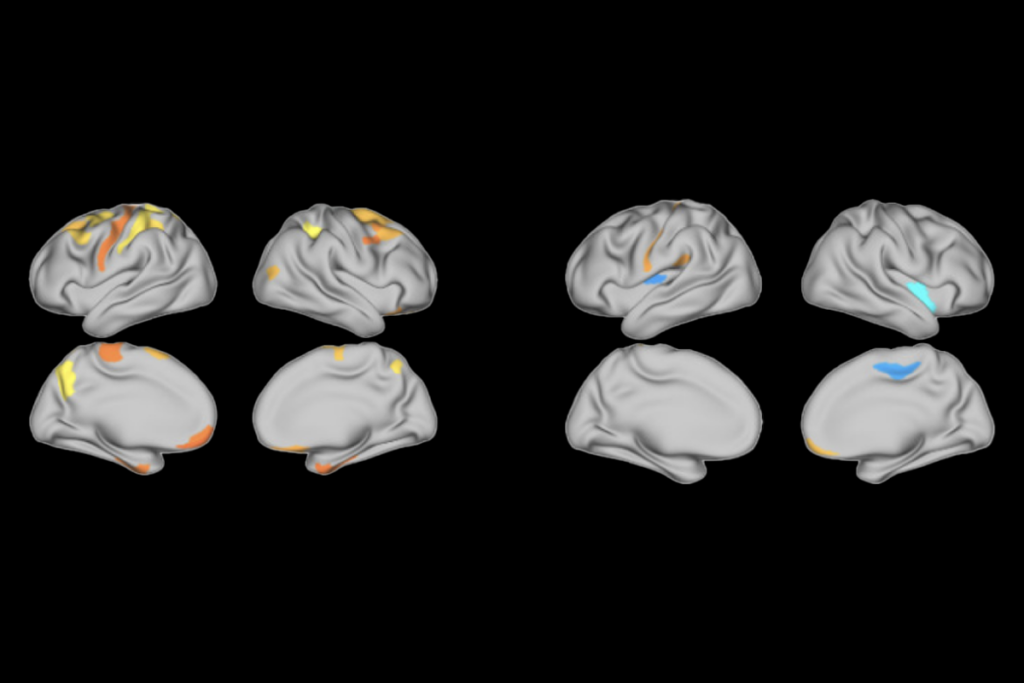

The team also measured how much each participant synchronized their facial expressions with their conversation partners. Typical people’s facial expressions tended to sync up and became increasingly aligned over the course of a conversation, but this was not the case for autistic people.

As a group, autistic people tended to be less synchronized in conversation than typical people. And atypical synchronization correlated with difficulties in social-communication skills, adaptive behaviors and empathizing abilities, as measured by standard checklists given to the participants’ mothers.

These differences tended to be more pronounced during conversations with the research assistant than with the participants’ mothers, suggesting that familiarity with a conversation partner influences facial expression patterns. The study was published in July in Autism Research.

“This isn’t just about what people with autism do with their facial expressions in interactions. It’s about how what they bring to the table may also influence their interaction partner,” says Casey Zampella, scientist at the Center for Autism Research at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, who led the study.

Humans and algorithms:

The results rely on a small sample of autistic people with relatively high intelligence quotients and verbal fluency scores, limiting the generalizability of the results, says Matthew Goodwin, associate professor of informatics at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts, who was not involved in the study.

The automated facial analysis also lacks the ability to determine what these facial movements actually mean for a human observer, says Ruth Grossman, associate professor of communication sciences at Emerson College in Boston, who was not involved in the study. “This machine-learning approach does not take into account the quality of the expressions; it only takes into account the presence of certain movements.”

Past research suggests that the upper and lower parts of the face can convey opposing emotional signals3. So, “by just looking at mouth movements, you’re missing whatever information the upper half of the face is signaling,” Grossman says.

Future studies could combine automated facial analysis with data from human observations to help interpret facial expressions, Grossman says. It could also be interesting to include physiological measures, such as heart rate, pupil dilation and sweat secretion, to determine the participants’ arousal levels during conversations, Goodwin says.

Herrington and his team hope to explore facial-expression patterns in various other contexts and interpersonal dynamics, he says.

“We looked at a particular group, in a particular moment in time, in a particular context,” Herrington says. “But what happens when they are angry? What happens when they are afraid? What about when they are in front of a group of people?”

They also plan to conduct larger-scale studies using tasks that are more feasible for autistic people with lower intelligence quotients and verbal fluency.

References:

Corrections

This article has been modified from the original. An earlier version incorrectly identified John Herrington as lead investigator of the new study.

Recommended reading

Latest iteration of U.S. federal autism committee comes under fire

‘Tour de force’ study flags fount of interneurons in human brain

FDA website no longer warns against bogus autism therapies, and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Betting blind on AI and the scientific mind