Genetics: Methylation may alter levels of autism gene

Postmortem brains from people with autism have abnormal patterns of chemical tags on SHANK3, one of the strongest candidate genes for autism, according to a study published 23 November in Human Molecular Genetics.

Postmortem brains from people with autism have abnormal patterns of chemical tags on SHANK3, one of the strongest candidate genes for autism, according to a study published 23 November in Human Molecular Genetics1.

These changes lead to differences in expression of the gene relative to controls, the study found. Specifically, the gene shows altered methylation, which influences gene expression without changing the underlying code. Brain methylation patterns change during an individual’s lifetime and may play a role in development. Methylation may be a way by which the environment influences gene regulation.

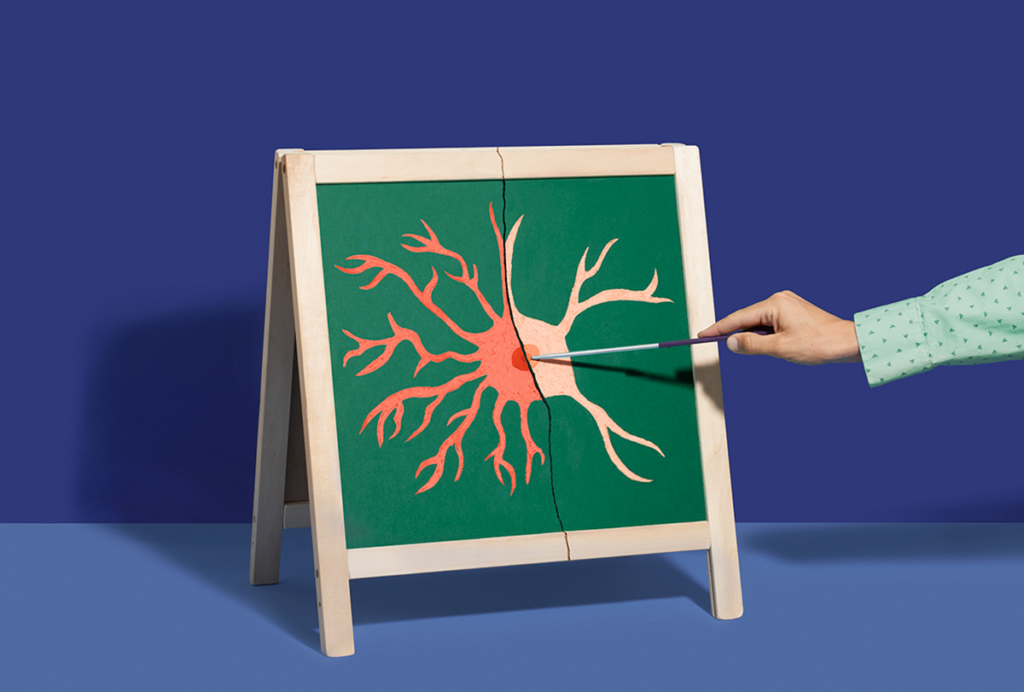

Studies have found several mutations and deletions in SHANK3 in individuals with autism. The protein organizes connections at neuronal junctions. More than one version of the protein, called an isoform, may be expressed by the same gene.

In the new study, researchers looked at postmortem brains from 54 individuals who had autism and 43 controls. They paid particular attention to five methylation-prone regions, called CpG islands, within the SHANK3 gene.

Three of these regions show elevated methylation in autism brains relative to those from controls, the study found. These autism brains have less SHANK3 message than do either autism brains with typical methylation or control brains. They also have little to none of certain variants of the protein.

Treating cultured cells with a drug that blocks methylation lowers the levels of some of these SHANK3 variants and raises the levels of others, supporting the role of methylation in SHANK3 expression.

The results suggest that SHANK3 may contribute to autism, even in individuals who have no mutations in the gene.

References:

1: Zhu L. et al. Hum. Mol. Genet. Epub ahead of print (2013) PubMed

Recommended reading

INSAR takes ‘intentional break’ from annual summer webinar series

Dosage of X or Y chromosome relates to distinct outcomes; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

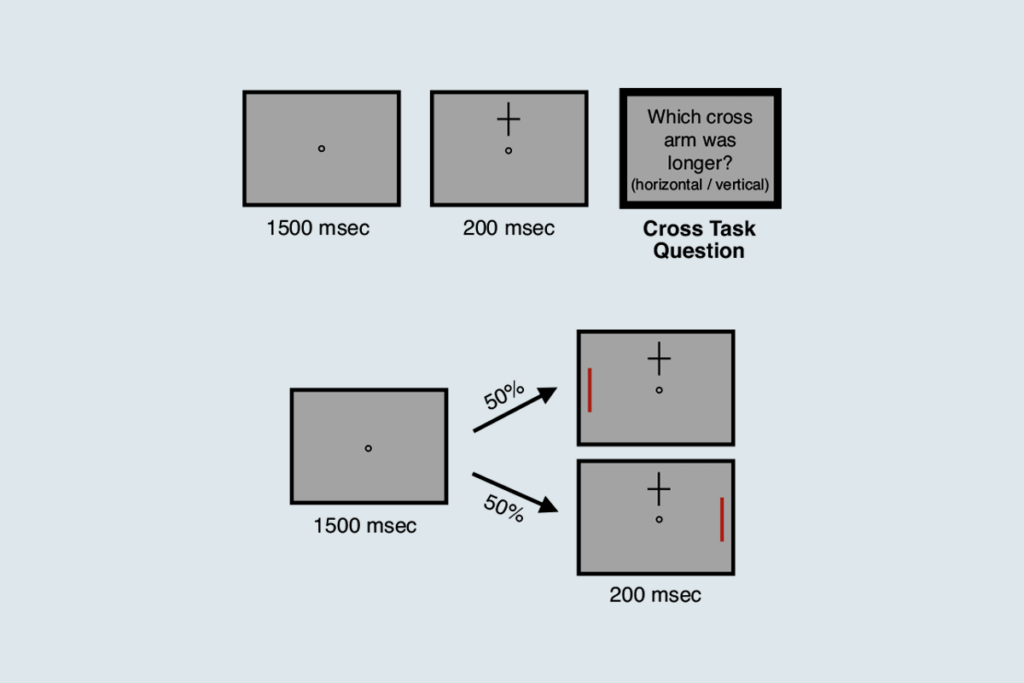

Attention not necessary for visual awareness, large study suggests