Autism is associated with a more than fourfold increased risk of early-onset Parkinson’s disease, according to the largest study yet to look for a potential link between the conditions.

Scientists investigated the medical records of everyone born in Sweden between 1974 and 1999, amounting to more than 2.2 million people. By the end of 2022, 438 of the 2,226,611 non-autistic people in the study, or 0.02 percent, had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s, compared with 24 of the 51,954 autistic participants, or 0.05 percent.

That translates to a 4.4 times greater risk of Parkinson’s among autistic people, an association that held up even after the researchers adjusted for sex, socioeconomic status and a family history of mental illness or Parkinson’s. Preterm and early-term birth, which previous research has suggested are associated with autism, did not appear to be connected with Parkinson’s. The results were published 27 May in JAMA Neurology.

“This is the first rigorous longitudinal study investigating this potential link between autism and Parkinson’s,” says Ezra Susser, professor of epidemiology and psychiatry at Columbia University, who was not involved in this work. “There is a lot that we may come to understand when it comes to the relationship between neurodevelopmental disorders early in life and neurological disorders later in life.”

Although other studies have found a higher proportion of parkinsonism in autism, this new investigation’s scale is “impressive,” says Sergio Starkstein, professor of psychiatry at the University of Western Australia, who was not involved in the research. “They studied the whole country,” he says. By contrast, in 2015, Starkstein and his colleagues found a 20 percent prevalence of parkinsonism in autistic adults, but they looked at only 56 people.

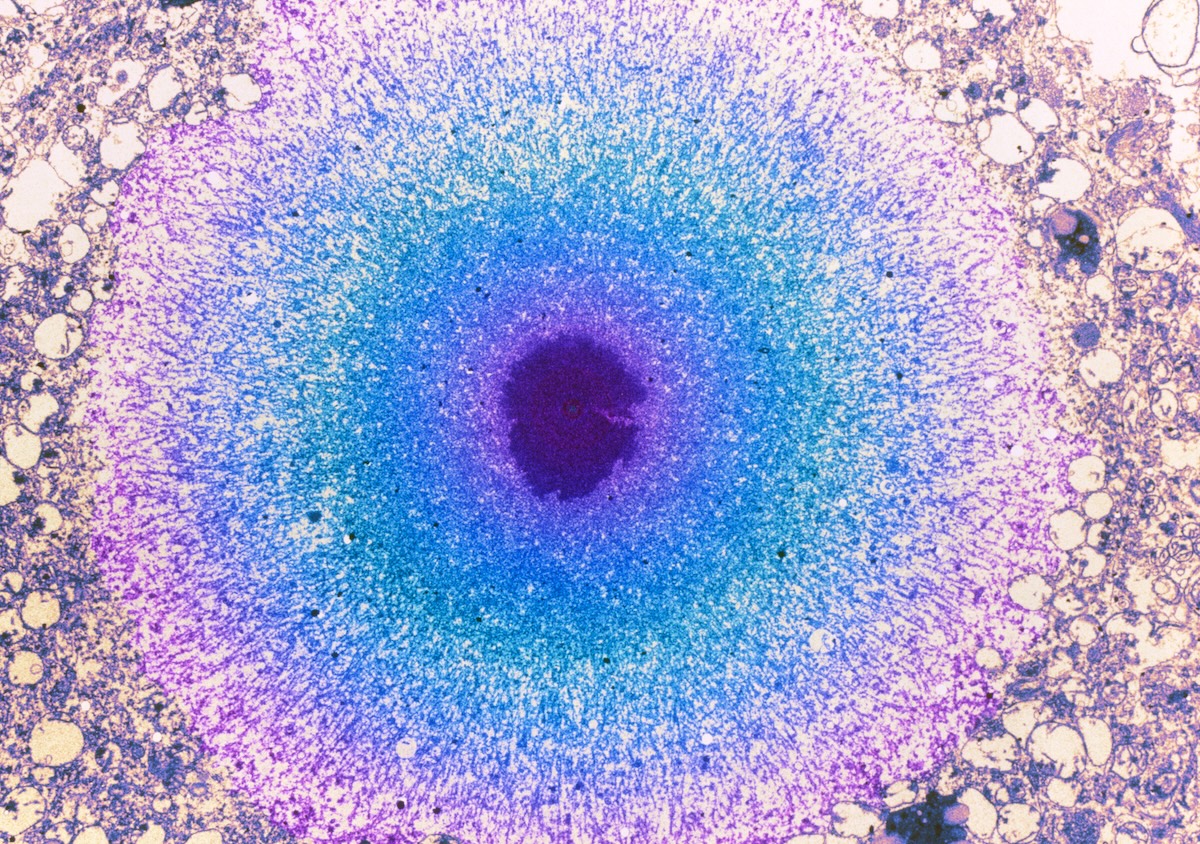

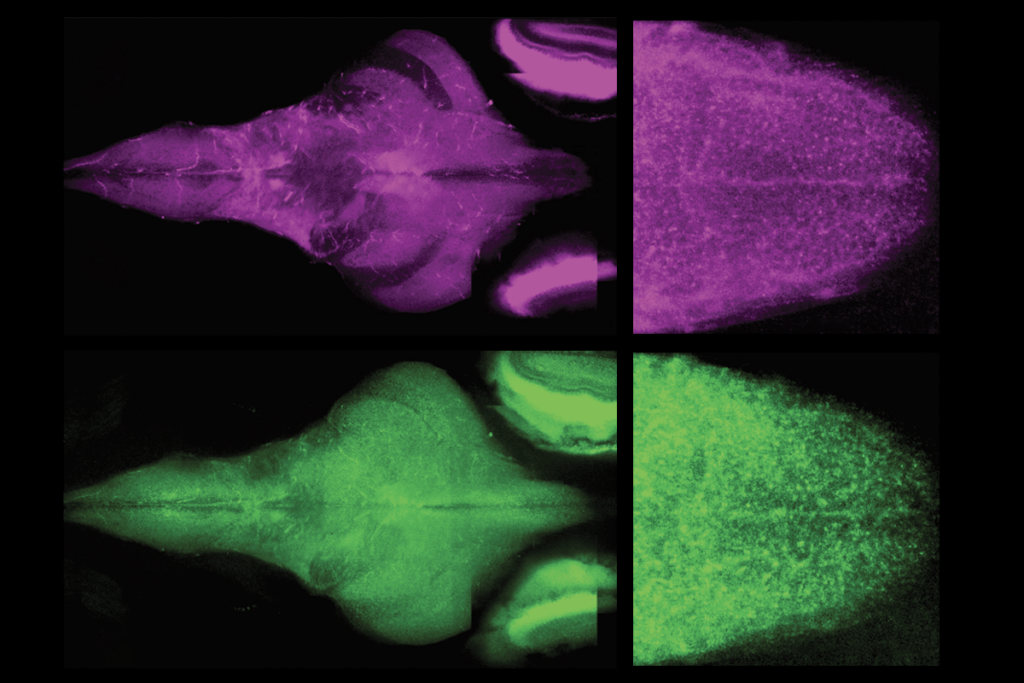

Autism and Parkinson’s disease may share biological links, previous findings suggest. For instance, autism is associated with variants in the PARK2 gene, which is also connected with early-onset Parkinson’s.

“The brain’s dopamine system is impacted in both conditions, as the neurotransmitter dopamine plays a crucial role in social behavior and motor control,” says study investigator Weiyao Yin, a postdoctoral researcher in the medical epidemiology and biostatistics department at the Karolinska Institutet.

Depression and antipsychotic drug use—both of which are common among autistic people—are associated with an increased chance of Parkinson’s or traits of the disease. But after adjusting for both of these factors, “autism spectrum disorder was still associated with a twofold increased risk of Parkinson’s disease,” Yin says.

A

nd autism, depression and antipsychotic use appeared to influence Parkinson’s risk independently of one another, based on comparisons between groups with and without these conditions. The risk of Parkinson’s may therefore be significantly more elevated for those with autism and co-occurring depression, antipsychotic use or both, Yin notes.Given the data they had, Yin notes that everyone studied was under 50 years old; the median age of the participants by the end of the study was 34. “A Parkinson’s disease diagnosis before the age of 50 is very rare, even among individuals with autism,” she says. As such, the cases identified represent early-onset Parkinson’s, which she cautions may have different risk factors and causes compared with later-onset Parkinson’s.

One potential limitation of this study is that the Swedish national patient registry did not start including outpatient data until about 2000, “and so may have been under-ascertaining people with autism before this time,” Susser notes. “I would like to see a study based on a fuller set of data to give more confidence in these findings.”

And Starkstein adds that “we can’t say for sure what the quality of the diagnoses were in this new study—there’s always going to be noise in these results. But that problem is compensated by the sheer size of the group they looked at.”

The findings suggest health-care services should keep autistic people under long-term observation for risk of such neurological conditions, said Sven Sandin, principal investigator on the study and a statistician and epidemiologist at the Karolinska Institutet, in a statement.

Starkstein notes that the new work suggests a subgroup of people with autism have a high likelihood of parkinsonism. “The challenge now is to precisely identify this subsample. That could be important in the proper planning of their health care and other services, and maybe in early treatment,” he says.

Yin says she and her colleagues now aim for larger studies with even longer follow-ups to identify such groups.