Microglia may be a key mediator between maternal immune activation and a pup’s memory of contextual fear conditioning in early infancy, a new mouse study reports.

The findings sharpen the picture of memory formation in early life, but the study’s approach to microglia has raised questions. That scrutiny comes as scientists reevaluate concepts such as synaptic pruning, through which microglia may shape neuronal circuits in early life and beyond.

Humans and rodents are unable to recall some of the earliest memories formed after birth. This period of infantile amnesia offers researchers a window to test conditions that may alter the survival of engrams, the changes in the brain tied to memory formation.

“Development is an experiment that nature does for you,” says study investigator Tomás Ryan, professor in neuroscience at Trinity College Dublin.

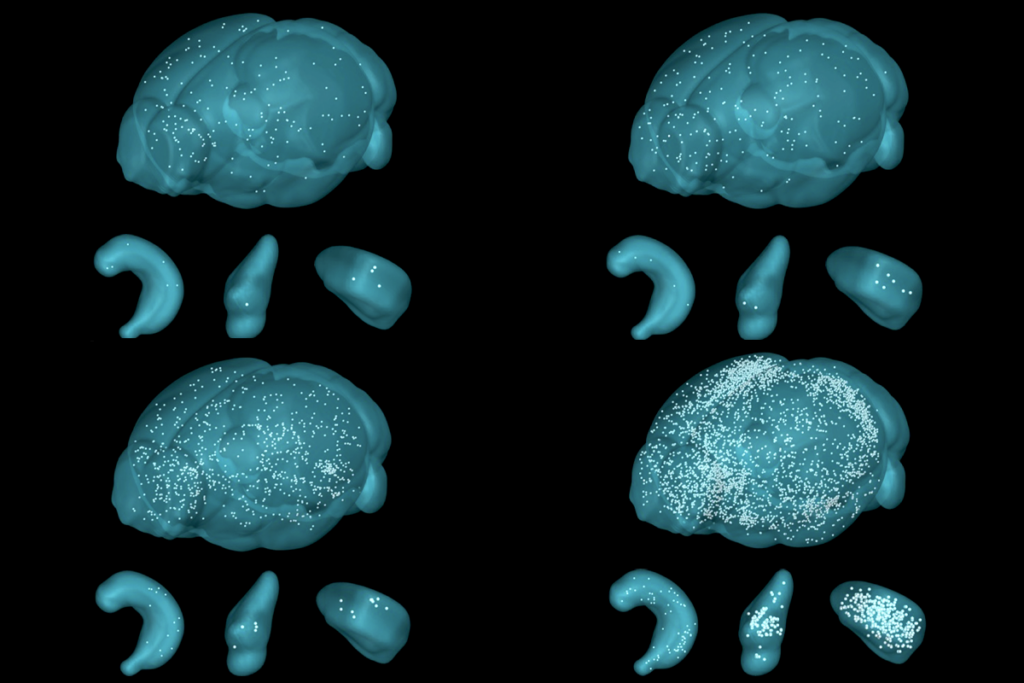

Activation of the immune system during pregnancy in mice leads to autism-like behaviors in their pups and reduces infantile amnesia, according to a previous study by Ryan’s team. Blocking microglial activity allows some infantile memories to persist in mice, Ryan and his colleagues report in the new paper, published 20 January in PLOS Biology.

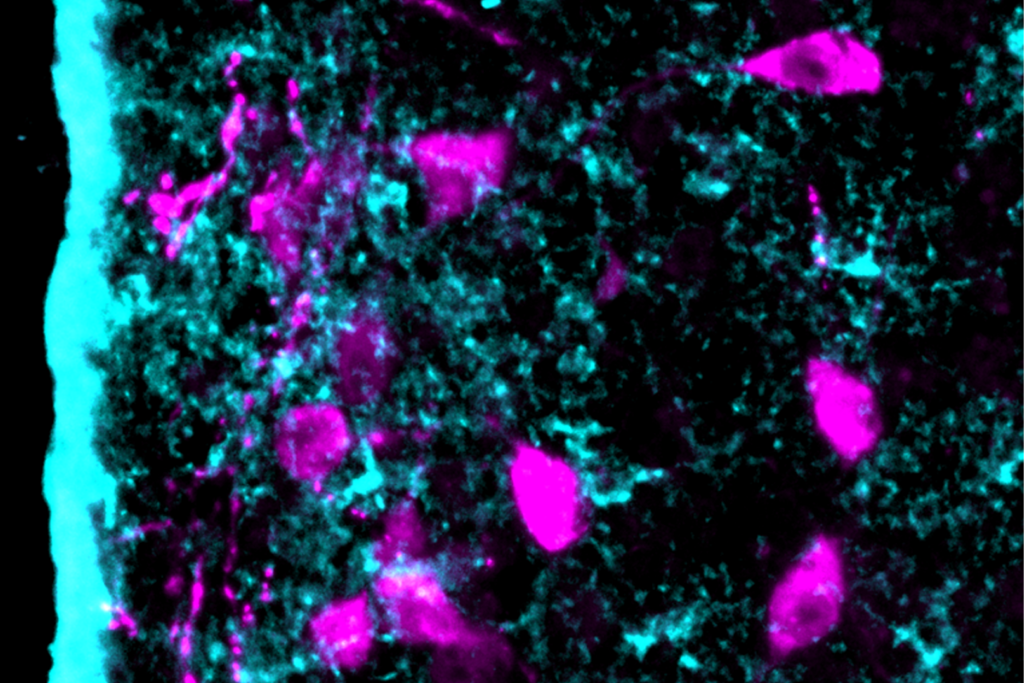

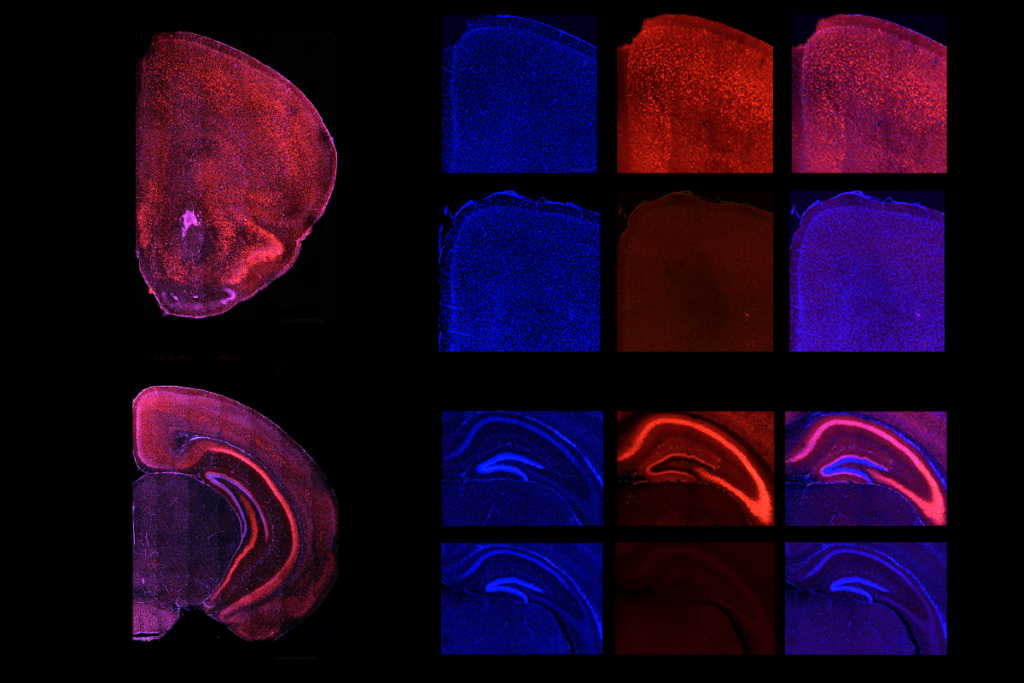

Administering minocycline in water daily starting one day before foot-shock conditioning at postnatal day 17 led to greater fear memory at postnatal day 25, after the typical onset of infantile amnesia. This recall was accompanied by a reactivation of associated engrams in the basolateral amygdala and central amygdalar nucleus.

In the pups of mice with maternal immune activation, deactivating microglia ahead of the foot-shock training allowed the fear conditioning to be forgotten during the infantile amnesia period, suggesting that microglial plasticity makes the effects of maternal immune activation reversible.

T

The findings have elicited mostly positive feedback at conferences prior to publication, Ryan says, but not everyone is convinced by his methods and conclusions.

For example, in experiments with and without maternal immune activation, the researchers used minocycline to deactivate microglia. However, the antibiotic does not target microglia specifically. “I personally don’t know what you can conclude from minocycline at all,” says Anna Molofsky, professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, who researches microglia but was not involved with the study. “There are plenty of better tools to study microglia out there.” The Transmitter sought comment from four independent developmental neuroscientists, and they all declined.

Ryan says that minocycline was the only option that offered high penetrance throughout the infant mouse brain without having to be delivered in a solvent that has its own apparent effect on microglia. “We used every microglial drug that we could get our hands on,” he says. “I feel the resistance against minocycline is reasonable when you have an alternative.”

F

Other than highlighting a role for CX3CL1 signaling, the investigators are agnostic about how microglia influence engrams. One mechanism proposed in the paper, synaptic pruning, has encountered skepticism in recent years. Even with real-time video evidence of microglia engulfing synapses, scientists debate the extent to which this process molds neuronal circuits.

Hippocampal synapses and dendritic spines are unaffected in a mouse model engineered to lack microglia, a 2024 study showed. Cortical and thalamic development continue unabated in this model, too, according to a follow-up by the same team. Although Ryan called this an “important and provocative paper,” he argued that mice may adapt to the congenital lack of microglia.

Microglial ablation studies have their weaknesses, Molofsky says. “It’s important to study specific functional pathways in microglia and understand mechanistically what they’re doing,” she says.“If you get rid of them, then you know you’ve eliminated the thing that you’re trying to study.”

The available evidence cannot rule out a role for microglial synaptic pruning in sculpting circuits. “When you’re trying to prove a negative, it’s very hard,” Frankland says.

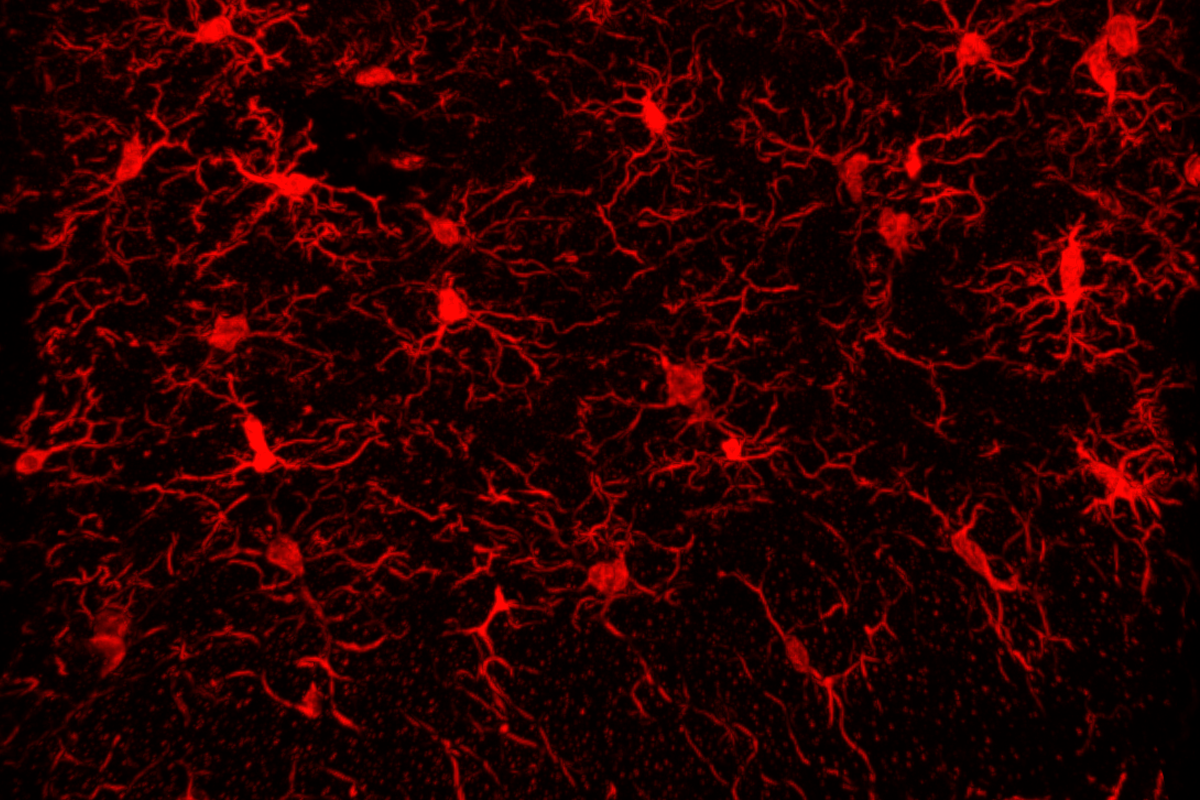

Another possibility is that microglia affect the extracellular matrix surrounding neurons, Ryan and his co-investigators wrote in the new paper. For example, they observed greater microglial branching and filament length in the dentate gyrus across the infantile amnesia period, and minocycline treatment led to fewer perineuronal net structures at postnatal day 25, though it did not improve engram reactivation in this area.

However microglia may act on neurons, Ryan says he doubts that the memory engrams themselves are affected. “I think it’s more plausible that the plasticity that’s causing the forgetting of an engram is extrinsic to that engram,” he says, suggesting that blocking microglia means “temporarily preventing the animal from forming new engrams during that time of exuberant learning … and as a result, the competing engrams don’t really form.”