Organoid study reveals shared brain pathways across autism-linked variants

The genetic variants initially affect brain development in unique ways, but over time they converge on common molecular pathways.

Different genetic variants associated with autism converge on common biological processes that shape the developing brain, according to a large study of organoids derived from autistic people’s cells. Individual variants initially alter neurodevelopment in distinct ways, but over time they all disrupt neuron maturation and other key processes, the study shows.

Previous work, including postmortem brain research, has explored the idea that different genetic changes linked to autism influence common brain pathways. But “proposing something is not the same as demonstrating it,” wrote Jürgen Knoblich, professor of synthetic biology at the Medical University of Vienna, in a comment to The Transmitter.

The findings—in brain organoids made from many autistic people with different genetic backgrounds— provide strong new evidence of this convergence, added Knoblich, who did not contribute to the work. “Truly heroic!”

The study is the first of its kind to test the idea of convergence using brain organoids in this way, says study investigator Daniel Geschwind, professor of human genetics, neurology and psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles. “The number of lines, the number of variants, the amount of replication—this has never been done before,” he says.

The work highlights the importance of studying many different autism-linked variants side by side to uncover shared biology, and it may inform future efforts to identify therapeutic targets, Geschwind adds.

Distinct genetic changes contribute to autism and lead to many shared traits, but the biological processes involved are unclear. In many other conditions, such as cancer, different causes ultimately affect the same core biological processes, Geschwind says.

G

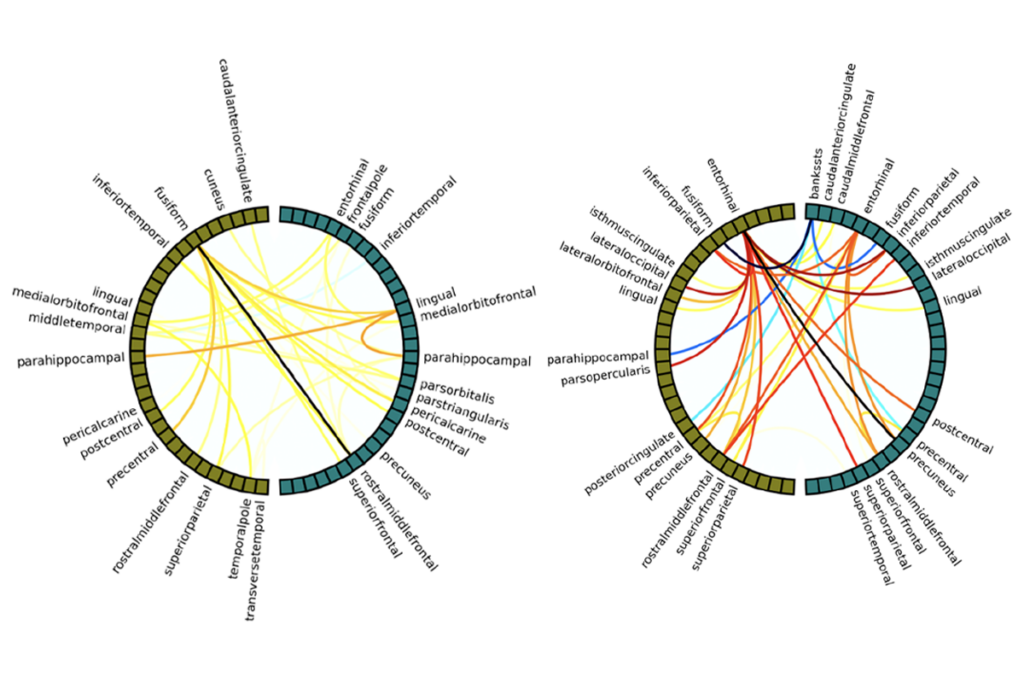

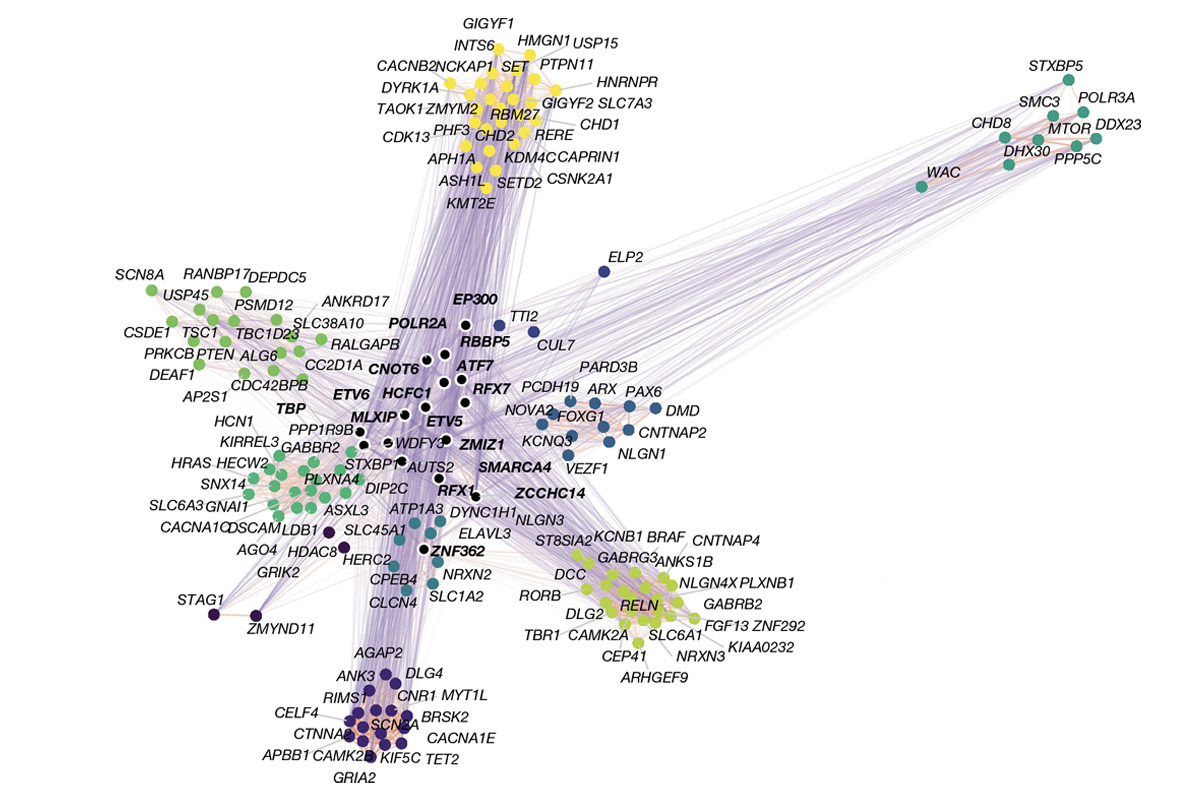

Early in the process, each genetic variant affected the developing organoid in its own way, but over time they began to disrupt common molecular pathways, especially those involved in neuronal differentiation, synapse formation and chromatin remodeling—the process that controls how genes can be switched on or off.

A core network of genes appeared to act as a “hub” controlling many of the downstream changes linked to autism; lowering the activity of genes in the network could influence the activity of other genes.

Organoids derived from 11 people with idiopathic autism did not show convergent changes, likely because the genetic effects in these cases are subtler than in people with known variants in major autism genes, says Geschwind, who added that the sample size was still too small to detect convergence. To address this problem, the researchers are now expanding their study to include additional variants and more cell lines from people with idiopathic autism. The team reported the findings last month in Nature.

P

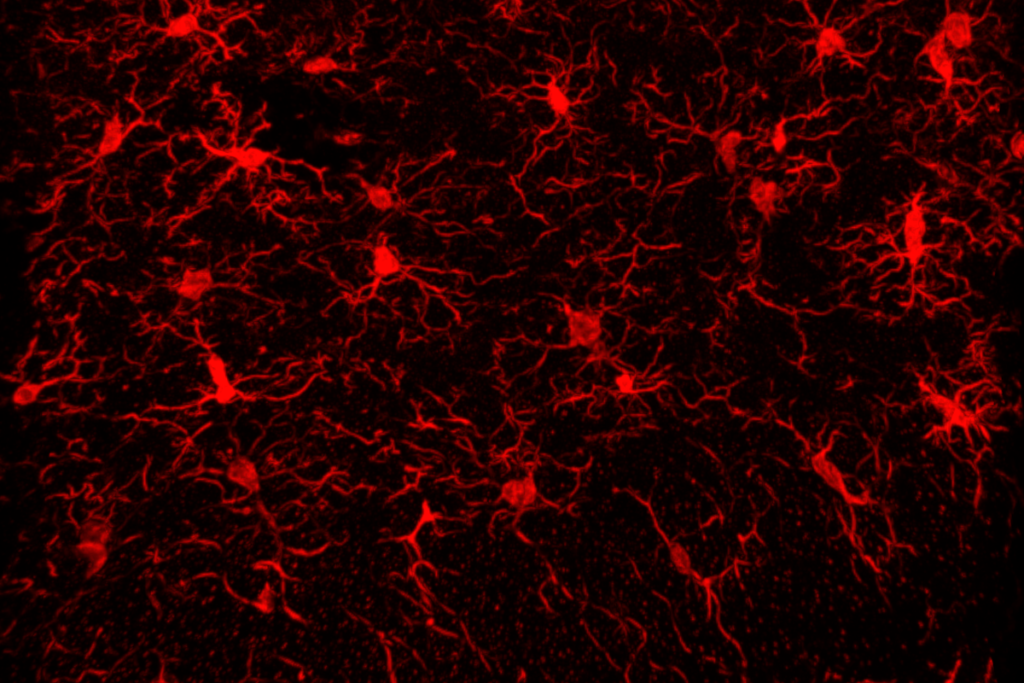

However, he notes, the newest findings rely on cortical organoids that are made mostly of excitatory neurons and lack important brain cell types such as interneurons, which are mostly inhibitory. Because the balance between excitatory and inhibitory neurons is thought to play a central role in autism, omitting these cells may mean that some key biological mechanisms are not fully captured, he says.

Overall, the new study isn’t about surprising discoveries but about bringing together and confirming what neuroscientists have long suspected, while giving them stronger tools to study how the brain develops in autism and related conditions, says Kristiina Tammimies, associate professor of medical genetics at the Karolinska Institutet. “It’s a great compilation of work,” she says.

A key finding is that autism-linked variants have distinct effects early in development—a stage that has been less studied compared with subsequent developmental stages—before later converging on shared biological changes, she says.

In the future, these shared changes could serve as biomarkers for screening drugs or testing potential therapies, Geschwind says. To make this next step possible, he and his colleagues plan to collect molecular, cellular and electrophysiologic measurements from the brain organoids. “We don’t expect that everything is going to converge on the same cell type or the same process, but we hope to identify subsets where one can see a refined convergence,” he says.

Recommended reading

Sex bias in autism drops as age at diagnosis rises

Microglia implicated in infantile amnesia

Explore more from The Transmitter

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures