Proposed guidelines won’t miss autism cases, study says

The proposed changes to the diagnostic criteria for autism are unlikely to exclude many people currently diagnosed with Asperger syndrome or pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified, according to a large analysis published today in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

The proposed changes to the diagnostic criteria for autism are unlikely to exclude many people currently diagnosed with Asperger syndrome or pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), according to a large analysis published today in the American Journal of Psychiatry1.

The study of more than 5,000 people found that the new criteria accurately identified 91 percent of people with autism-related diagnoses under the existing criteria, and suggests that the new version can better distinguish autism from other developmental disabilities.

The new criteria are outlined in the DSM-5, the forthcoming edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, due out in May 2013.

The most controversial change in the DSM-5 is that the different disorders now collectively referred to as autism spectrum disorders or pervasive developmental disorders will be subsumed under the single heading of autism spectrum disorder.

The concerns about the DSM-5 arose from several studies published over the past year suggesting that the new criteria would exclude a significant number of people, particularly those with Asperger syndrome or PDD-NOS, who are high functioning and have mild symptoms.

The reports generated a great deal of controversy in both the general media and scientific journals because in many cases, losing a diagnosis could also result in a loss of benefits and services.

“The biggest thing that I think is important for the public to understand is that the current draft of the DSM-5 is not likely to miss cases any more than the previous criteria were,” says Thomas Frazier, research director of the Center for Autism at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. “I think this paper puts that issue to bed.” Frazier, who was not involved in the new study, has come to the same conclusion through his own research.

Careful collection:

A major criticism of some previous studies of the DSM-5 is that the data they used, often collected from brief questionnaires, do not include information required by the DSM-5 criteria. For example, the DSM-5 criteria include sensory problems, which are not part of the DSM-III or -IV.

“Some of the studies in which children fail to meet criteria are poor in quality,” says David Skuse, chair of behavioral and brain sciences at University College London, who was not involved in the new study. “They are nowhere near as carefully done as this one, in terms of the number of cases and the range of clinical material they used.”

The new study analyzed 4,453 individuals with an autism spectrum disorder and 690 people with other diagnoses, such as language disorders or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

“What we were trying to do is systematically look at any large samples we could get our hands on,” says lead investigator Cathy Lord, director of the Institute for Brain Development at New York-Presbyterian Hospital in New York City.

The study includes 1,021 children from the Collaborative Programs of Excellence in Autism, a multi-site effort funded by the National Institutes of Health, and 1,992 children from Lord’s former clinic at the University of Michigan. It also includes 2,130 children from the Simons Simplex Collection — a collection of families that have one child with autism but unaffected parents and siblings, which is sponsored by SFARI.org’s parent organization.

“In combination, it’s a much bigger sample than anyone else had and gives us more data,” says Lord, who is also a member of the committee revising the DSM-5 autism guidelines.

Each of the children had undergone the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised, or ADI-R, a parent report of autism symptoms, and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, or ADOS, an hour-long clinical observation tool. (Lord developed these tests.)

Though these are detailed tests, neither one was developed explicitly to collect the information needed for diagnosis using the DSM-5.

“It’s still not the same thing as taking the new criteria and testing them out, which is why we didn’t do this analysis before,” says Lord. “But clearly people have been analyzing much more restricted datasets, so we thought we better get in here and do it.”

Lord and her colleagues found that the DSM-5 is as sensitive as the DSM-IV, meaning it accurately identifies those who have autism. The DSM-5 criteria also have better specificity than those in the DSM-IV, meaning they can better distinguish between people who have autism and those who have other developmental disorders, the study found.

The findings are in line with preliminary results from field trials of the DSM-5, presented at an autism conference in May. Those results also suggested that the new criteria would exclude few people currently diagnosed with autism.

Real world:

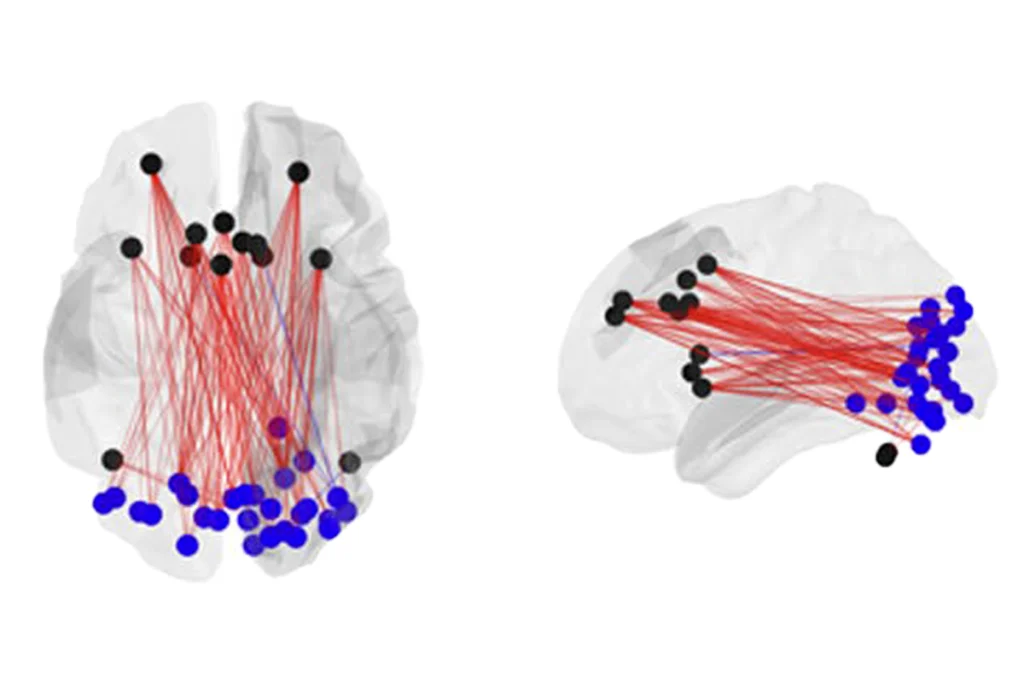

In the DSM-5 criteria, symptoms of autism are split into two main categories: social communication deficits and restricted and repetitive behaviors. One of the major concerns with the DSM-5 has been whether it will exclude some people with PDD-NOS. Some studies suggest that people with PDD-NOS have fewer restricted and repetitive behaviors than those with other autism diagnoses2.

The new paper refutes these concerns, showing that only a small percentage of people with PDD-NOS fail to meet the new guidelines, and only because of fewer social communication symptoms.

“We didn’t see any evidence that there would be dramatically lower diagnosis of people with Asperger’s or PDD-NOS,” says Lord.

Skuse says he is surprised by this finding, because in his own clinical sample, he finds more people who have social communication deficits but not restricted and repetitive behavior problems than the reverse pattern.

Fred Volkmar, director of the Yale Child Study Center and a vocal critic of the DSM-5, says he is concerned that the study’s setting does not represent the real world.

“The trouble is, these are very well-characterized cases in research studies with high-level experts, so you’re getting a rosy scenario,” says Volkmar. “In that scenario, the [guidelines] work well. But a book like the DSM is meant for clinical use as well.”

For example, not all clinicians use the ADOS and ADI-R — time-intensive tests that require extensive training to administer — to diagnose autism.

Lord responds that the same concern applies to the existing guidelines as well. “I think it’s true that we do need to think about how we expect non-specialist clinicians to make diagnoses — that’s a whole other issue, but was just as relevant for DSM-IV,” she says. “Even very skilled clinicians had difficulty using the DSM-IV, in terms of the distinctions among the different types of [autism].”

The best solution to these concerns is to educate providers and improve tools, others say.

“I don’t think the answer to [Volkmar’s] criticism is that [the criteria] have to be relaxed,” says Frazier. “Finding a tool that doesn’t take so much time and expertise is important.”

The debate is likely to linger until the DSM-5 criteria have been evaluated in so-called prospective trials — studies that collect data expressly for the purpose of comparing the DSM-IV and DSM-5 — rather than relying on previously collected data.

Autism Speaks, a research and advocacy organization based in New York, is funding one such study. Researchers at the Medical University of South Carolina plan to screen 8,000 school children for autism risk, and then use both DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria to assess those considered to be at risk.

“It will be really helpful to see what the Autism Speaks prospective study will turn out, but that will be years from now,” says Lord.

References:

1: Huerta M. et al. Am. J. Psychiatry 169, 1056–1064 (2012) PubMed

2: Mandy W. et al. Autism Res. 4, 121-131 (2011) PubMed

Recommended reading

How pragmatism and passion drive Fred Volkmar—even after retirement

Altered translation in SYNGAP1-deficient mice; and more

CDC autism prevalence numbers warrant attention—but not in the way RFK Jr. proposes

Explore more from The Transmitter