Reporter’s notebook: Highlights from INSAR 2025

The annual meeting brought autism researchers, advocates and clinicians to Seattle to discuss the latest research, including attempts to define subgroups, a potential new CHD8 macaque model and life expectancy gaps.

SEATTLE—From 30 April to 3 May, nearly 2,300 attendees from more than 50 countries gathered at the Seattle Convention Center for the International Society for Autism Research (INSAR) annual meeting to discuss the latest scientific advances in autism research. As INSAR science chair Meng-Chuan Lai, senior scientist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Canada, noted in his opening remarks, autism researchers and advocates had gathered for the meeting amidst “unprecedented political times.”

Some speakers alluded to threats to research funding in the United States—a prospect that new INSAR president Brian Boyd also took up in a commentary for The Transmitter. Tension between the scientist and autistic communities also arose in discussions during the meeting. In one keynote, autistic scientist and activist Dora Raymaker, research associate professor of social work at Portland State University, invited attendees to imagine a future in which the two groups collaborate in creative, productive ways. She encouraged the audience to “embrace many ways of knowing” and cautioned people against rejecting “a paradigm just because it was used for harm in the past.”

Over the course of the meeting’s four days, many familiar scientific threads cropped up in posters and panel sessions. Here are just a few themes of note—and we urge readers who attended to add their observations in the Comments section.

- Several scientists discussed their efforts to define subgroups within the autism spectrum. For example, Michael Lombardo, senior researcher at the Italian Institute of Technology, presented evidence that clustering data related to a child’s early language, intellectual, motor and adaptive functioning yields subtypes with distinct developmental trajectories over the first 10 years of life. Other research groups highlighted approaches involving brain imaging, transcriptomics, deep learning and other clinical features.

- Multiple researchers discussed the definition of “profound autism.” Catherine Lord, George Tarjan Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry and Education at the University of California, Los Angeles, described the Lancet Commission’s approach to this task and the results of a Delphi consensus process to survey clinicians on their understanding of this term. And Matthew Siegel, chief of clinical enterprise in the psychiatry and behavioral sciences department at Boston Children’s Hospital, presented findings from the Autism Inpatient Cohort suggesting that measures of adaptive functioning are a powerful tool for identifying autistic people with the greatest support needs.

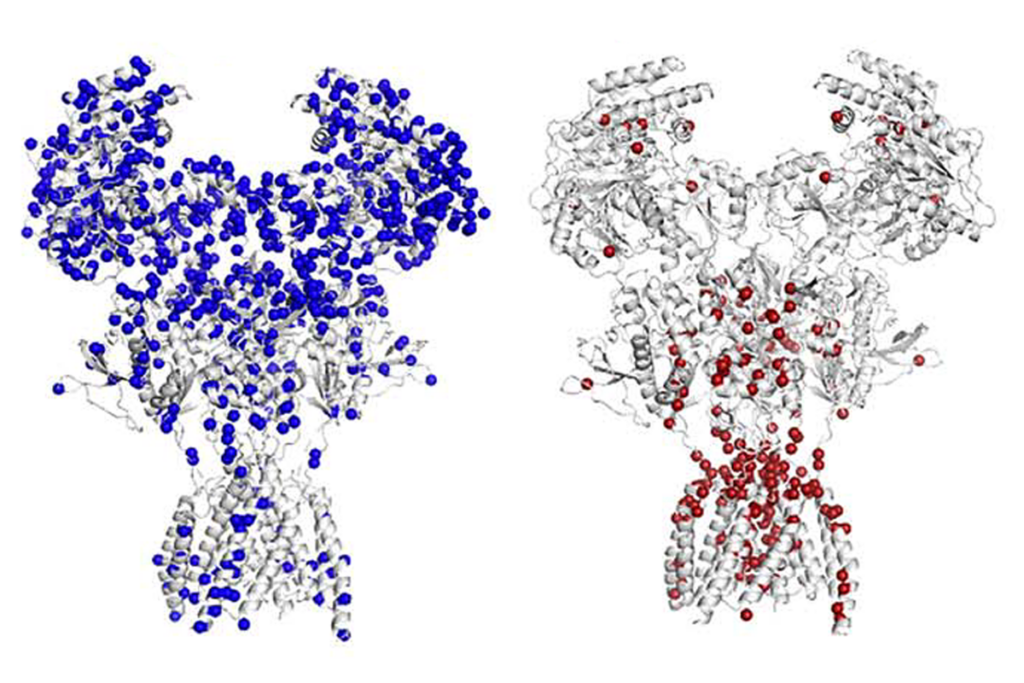

- Work discussed at other panels and sessions explored the long-debated role of excitation and inhibition in autism. For example, Viola Hollestein, a research associate in forensic and neurodevelopmental sciences at King’s College London, presented preliminary results from AIMS 2 LEAP suggesting strong links between a person’s polygenic score for thalamic glutamate (an excitatory mechanism) and social responsiveness. During a panel on brain wiring, Alexia Stuefer, a postdoctoral researcher in functional neuroimaging at the Italian Institute of Technology, described how chemogenetically inducing excitation in transgenic mice during a particular window in early development leads to enduring changes in sociability and the responsiveness of pyramidal neurons. In that same panel, So Hyun Kim, associate professor of clinical and counseling psychology at Korea University, shared findings from work that used the aperiodic exponent of EEG power as a proxy for an excitation-inhibition imbalance.

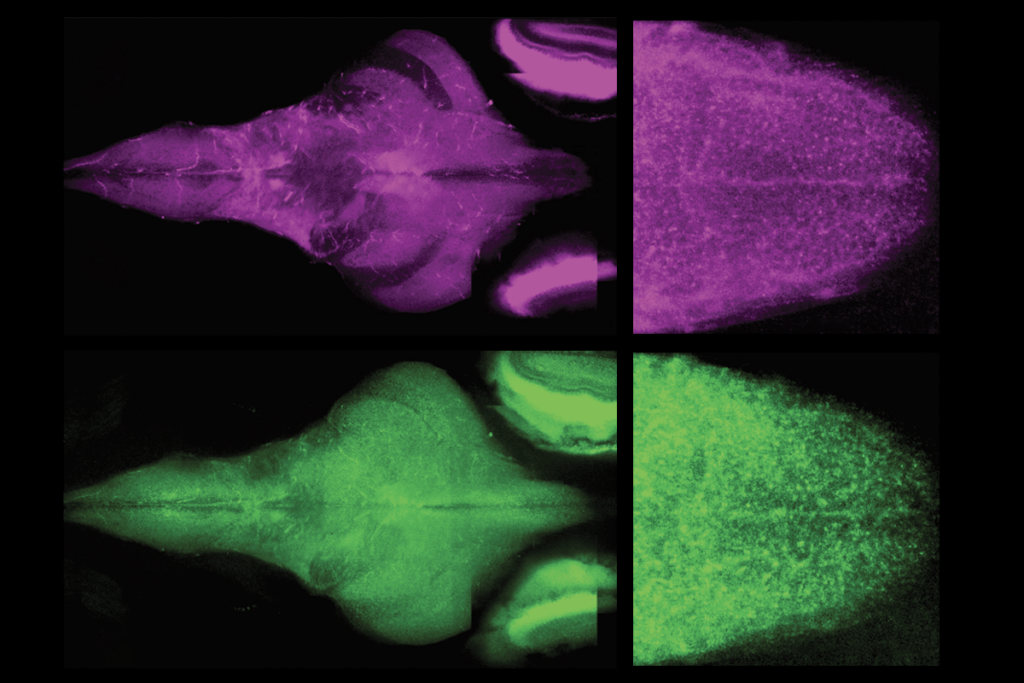

- Finding animal models and reliable biomarkers remain critical efforts in autism research. In a panel focused on fragile X syndrome, for example, Sarah Lippé, professor of psychology at the Université de Montréal, discussed how changes in EEG markers might reflect the severity of behavioral traits in people with this condition. Later, Khaleel Razak, professor of psychology at the University of California, Riverside, presented findings on temporal processing in a fragile X mouse model. And in a separate session focused on rare animal models, David Amaral, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis MIND Institute, described a potential new CHD8 rhesus macaque model.

- Epidemiologist Guohua Li of Columbia University presented findings on the life expectancies of Medicaid beneficiaries with autism in the U.S., based on data from 2000 to 2020: Autistic people on Medicaid live 14 years less than those who are privately insured and 6 years less than the general Medicaid population. The biggest gaps were among autistic people who identified as Hispanic or as women. The COVID-19 pandemic may have had an especially significant impact on autistic people. According to 2020 data, deaths in the autistic population on Medicaid increased by double what was seen among privately insured autistic people and the general population on Medicaid, Li noted.

- Several research groups described their efforts to employ video tools and artificial intelligence to better assess and understand autism features across a variety of domains. As just one example, Ilan Dinstein, professor of psychology at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, discussed his work tracking both stereotypical movements and facial expressions in autistic children using machine learning.

- “I was going to do one year of research” before going into private practice, recalled Joe Piven, professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, during an acceptance speech for a lifetime achievement award. Piven shared how that one year became a decades-long career, highlighting the power of “happy accidents” that propelled his interest in child psychiatry, autism and genetics.

Recommended reading

Largest leucovorin-autism trial retracted

Pangenomic approaches to the genetics of autism, and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Anti-seizure medications in pregnancy; TBR1 gene; microglia

Emotional dysregulation; NMDA receptor variation; frank autism